Vol. 41 (Issue 05) Year 2020. Page 21

PAVONE, Pietro 1

Received: 25/10/2019 • Approved: 08/02/2020 • Published 20/02/2020

ABSTRACT: In the economy of globally interconnected phenomena, the relationships between companies take place according to the logic of reciprocity and interdependence. In the Multinational Firms, the distorting effects of transfer pricing, arising from the lack of an effective alterity between companies, worries the tax authorities. Therefore, the definition of transfer pricing policies is crucial for managers, and must involve an interaction between business and tax elements. This study examines the possibility of distinguishing legal transfer pricing from the manipulative one. |

RESUMEN: En la economía de los fenómenos globalmente interconectados, las relaciones entre empresas tienen lugar según la lógica de reciprocidad e interdependencia. En las empresas multinacionales, los efectos distorsionadores de los precios de transferencia, derivados de la falta de una alternativa efectiva entre las empresas, preocupan a las autoridades fiscales. Por lo tanto, la definición de políticas de precios de transferencia es crucial para los gerentes y debe involucrar una interacción entre los elementos comerciales y fiscales. Este estudio examina la posibilidad de distinguir el precio de transferencia legal del manipulador. |

Appropriate tax planning can reduce the company's tax liability without necessarily reducing the accounting income reported in its financial statements (Rego, 2003; Richardson and Lanis, 2007). The freedom of Multinational Firms (MNFS) to set, in relations with other group companies, the most suitable prices for the objective of minimizing the overall tax charge, meets a limit when the transaction takes place between companies resident in different States. In fact, when the companies of the group belong to different tax jurisdictions, there is a real risk that, by properly calibrating the prices in intercompany transactions, positive elements of income are channeled to companies located in areas with lower taxation (Slemrod and Wilson, 2009), and attributed negative income elements to companies resident in states with higher tax rates; or, again, that revenues on loss-making companies and costs on profitable companies be channeled. The problem derives from the fact that for the States the way in which the incomes of the multinational group are determined and distributed among the subsidiaries is not indifferent, since each State has the interest in that the tax bases of the units of the group residing on its territory they are not impoverished by appropriately designed intra-group transactions.

So, on the one hand, companies have an interest in using the transfer price to shift profit between tax jurisdictions with differentials in tax rates, minimizing corporate tax, and on the other hand, tax authorities in different states have interest, exactly the opposite, so that this does not happen. Moreover, to aggravate the state of tension between the actors involved, is added the harmful tax competition between the States, both because they decide different tax rates, and in the concrete of the inspection action because it is very probable that the tax authority of the subsidiary to which goods or services have been sold at high prices will not object the transfer price, since the tax revenue of that country increases; instead, the tax inspectors of the parent company will criticize the existing transfer price and the lost tax revenue (Wong, Nassiripour, Mir and Healy, 2011).

In a context in which the tax revenues of the states decrease and the profits of the multinationals increase, the issue of transfer prices is a significant source of tension MNF and tax authorities (Wray Bradley, 2015).The circumstance is also confirmed by several studies that have shown a mirror behavior of MNFs (taxpayers), which consider the tax on marginal profit deriving from transfer prices as a cost to be avoided through strategic tax planning, and the States (legislators and tax authorities) that consider these taxes an important part of public revenues. The consequent tension between the "attractive" force exercised by the States and the "repulsive" force of the MNFs is also evident from some empirical researches (Hines, 1997; Weichenrieder, 2009; Clausing, 2003). Bartelsman and Beetsma (2003) have already pointed out that the countries of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD countries) have increased their taxes but have not collected more tax revenues from the MNFs, which have responded by increasing the practices of income shifting through transfer prices.

The present contribution, while presenting obvious practical implications, is based on a predominantly theoretical approach. In particular, an exploratory-descriptive research methodology is used, suitable to frame the transfer pricing according to a conceptual construct that considers both perspectives: that of the taxpayer (MFN) and of the tax authority, both in search of a difficult equilibrium between the "slippery soils" of the lawful tax saving and tax evasion and avoidance. The dual dimension of the phenomenon is known in the literature: Hyde and Choe (2005) have even advanced the idea that MNFs would use a «double accounting» for transfer prices: one for management purposes and one for tax purposes, so much so that other researchers (Anctil and Dutta 1999; Smith 2002; Baldenius, Melumad and Reichelstein, 2004) have suggested to reach a theoretical and practical separation of this «double track», building several transfer prices for tax purposes and for control and management purposes.

The file rouge of this study is represented by the effort to deepen the different approaches to the same theme by the two main actors able to influence the dynamics of it future development: MNFs and tax authorities. The hypotheses on which the work is based and develop can be defined as follows:

- H1: the borderline between lawful transfer pricing and fraudulent transfer pricing is not always clear;

- H2: there are different business approaches to transfer pricing that can lead to different tax outcomes.

In the first part of this study, after reviewing the literature, it will be possible to create the premises to answer the following research question (RQ):

- RQ: Conceptually, is it possible to distinguish correct or acceptable transfer pricing policies from those that determine basic erosion and profit shifting phenomena?

The reasons for the research questions emerge:

- from the importance and actuality of the issue both in the more developed and in the emerging economies;

- from the observation of empirical phenomena not resolved by existing interpretative models.

In the central part of the paper, the analysis will concern the research of the natural dimensions of the transfer pricing and then of some frequent features

that open to the examination of the pathological dimensions concerning the determination of transfer pricing in MFNs.

Some concluding remarks, after a focus on the peculiarities of the inspection action of the Italian Tax Office, find in the progressive overcoming of the traditional purely tax-based conception of the State the prerequisite for dissolving the tensions that have always animated the opposing positions of MNFs and tax administrations on the subject of the determination of the transfer prices, of their possible alterations and of the consequent remarks of the tax authorities for the recovery to taxation of what is not declared.

In the past, transfer pricing was a typical concept of managerial accounting. So much so that the first studies on transfer prices (Dean, 1955; Heflebower, 1960), up to about the 1960s, do not concern the fiscal problems relating to transfer pricing, but deal with aspects of a purely managerial nature.

Subsequently, hand in hand with the decentralization and divisional development of companies (Grabski, 1985), managers begin to use, sometimes abusing, transfer pricing to internally allocate profits between different divisions and segments in more cost-effective way (Levey and Wrappe, 2010). It was in the 1930s that the issue of transfer prices entered the fiscal debate when some MNFs in the United States began using it for tax avoidance purposes. In opposition to these new practices, in 1935, the United States introduced business alignment with market values in the determination of transfer prices.

The same measure was adopted by the OECD many years later, in 1979 (Morris, 2011), to which many European legislators, including the Italian one, have progressively adapted. Since then, many academic researchers have also begun to study the most hidden and profound aspects of transfer pricing practices, immediately encountering the main difficulty of not being able to access confidential data exclusively owned by companies. Consequently, many studies (Grubert and Mutti, 1991; Collins et al., 1998; Desai et al., 2006; Dharmapala and Riedel, 2013), although useful for better understanding the ways in which the phenomenon manifests itself in practice, have the limit of offering empirical results based on public data and, therefore, not considering particular business decisions and conditions. Moreover, according to Mataloni and Fahim-Nader (1996), most of the first studies in the literature, following Horst's theoretical approach (1971), are based on the hypothesis that the subsidiaries are 100% controlled, which is certainly not the only case history in reality, not considering the large number of non-totalitarian holdings. Starting from Kant's research (1988) some authors show that "ideal" transfer prices can be very different in the case of non-totalitarian holdings.

If a part of the authors tries to reconstruct the optimal transfer prices, other authors are more interested in the negative effects from the point of view of taxation. Grubert and Mutti (1991) and, after them, Shackelford et al. (2007) highlight that "abusive" transfer pricing often involves goods or services for which there are no available sales data (mainly, intangibles), complicating the work of tax authorities.

In addition to the distinction between authors who study the optimal price and the authors who study the fiscal essence of transfer pricing, another fundamental distinction concerns the double approach, macroeconomic and microeconomic, to the theme offered by economic theory. With regard to the first profile, relevance is given to the effects produced by the processes of productive delocalization on the income distribution between States.

This means that when an MNF decides in which state to produce, it is also deciding in which state it pays taxes. In this perspective, for example, Bartelsman and Beetsma (2003) show how the different methods of determining transfer prices can differently affect the tax revenues of some countries. Instead, on the microeconomic level, the focus is on the disjointed strategies of the value chain created by the MNFs to search for more agile and flexible organizational structures. According to this interpretation, other authors (Jacob, 1996, Conover and Nichols, 2000) show that the largest companies have greater chances of shifting income through transfer prices.

Finally, a selected and qualified group of authors dealing with the issue manages to outline the first signs of a highly contradictory and conflicting relationship between tax authorities and taxpayers. In this sense, Eden (1983), in analyzing the effect of Canadian tariff regulations on the transfer prices of companies, is convinced that companies are able to change their production levels to compensate for the effect of the rules tariff. Prusa (1990), drawing on the natural information asymmetry between companies and tax authorities, reaches similar conclusions: companies can manipulate transfer prices, changing production or marketing decisions if necessary. The empirical results of Weichenrieder (2009) also show that several EU MNFs have shifted profits to their German affiliates when Germany had lower tax rates.

The internationalization of intercompany transactions increases the percentages of operational and structural efficiency of the group, stabilizing the flow of results at a global level over time, and limits the overall business risk. In managing these relations, a role of absolute strategic importance is assumed by the transfer pricing policies. Given the nature of an essentially and preliminarily technical-administrative instrument of transfer pricing, it follows that transfer pricing policies, free from distorting effects, must be able to perform two main functions:

- allow weighted decisions on the right amount of goods and services to sell or buy;

- allow the control and evaluation of the performance of the business units (Abdallah, 2004): the managers at the head of the divisions are also remunerated based on the performance of their divisions.

This first and original nature of transfer pricing leads the MNFs to place the aspects inherent to it in the "Corporate management area" (Figure 1). However, considering the tax costs in the same way as any other cost related to the business of the company, seeking its unbridled minimization, has often led companies to structure their tax department with the aim not only of implementing all the necessary formalities to be compliant with the tax regulations of the countries in which they operate, but also in order to identify the possibility of reducing the overall tax charge of the group. In this second case, transfer pricing is a theme managed exclusively by the "Tax area". Each of these areas can be further subdivided into sub-categories (for example, fiscal compliance, fiscal control, tax reduction, etc., as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1

The two operational cores of transfer pricing

Source: from Novikovas M. (2019, “Evaluation of theoretical and

empirical researches on transfer pricing”, Ekonomika, 90(2).

Adaptation of the author.

The propensity towards the managerial or fiscal aspect of transfer pricing determines the company approach to transfer pricing dynamics. When the distance between the two areas (corporate management area and tax area) increases, it means that the company operates using only one or the other approach to transfer pricing; in both cases, increasing the tax risk associated with its cross-border operations. Many managers recognize that the transfer pricing taxation cannot be managed independently of business activities because this can have a significant influence on the decisions relating to the transactions to be carried out (KPMG, 2005).

However, far from considerations of a fiscal nature, in the perspective of the company and in a broad sense, the transfer pricing can also be directed to develop group policies for strictly economic purposes: for example, the case in which a transfer of assets with lower values than those normally applied takes place in order to allow the subsidiary to gain market share, through the subsequent sale of products at highly competitive prices.

However, from the physiological point of view, there are subjective evaluations based on the economic-corporate determination of transfer prices, because they depend on factors that cannot be objectively measured (for example, the internal technological environment, social environment, external technological environment and external institutional environment, according to Li and Ferreira, 2008). Thus, discretionary choices, even if legitimate, re-propose in the transfer pricing decision the same problems that afflict the issue of balance-sheets policies in the preparation of the financial statements between correct accounting and creative or fraudulent accounting. The area of discretion is extended considering that, in choosing the method to determine the transfer prices, the MNFs are allowed to adopt, justifying the reasons, the criterion deemed most appropriate, even if it is not among the methods explicitly indicated by the regulations. Furthermore, the economic relations between the companies of a group are almost never unidirectional: the parent company is not always the active part of the transaction: it may happen that other companies decide to sell goods or provide services (administrative, accounting, logistics, research and development, marketing, etc.) in favor of the parent company, just as it can also happen that within the same group there are more companies that offer some services to other subsidiaries. Therefore, a further critical point is that commercial operations are managed by the managers of the subsidiaries in the different countries, but these managers do not fully know the tax strategy existing at the group level.

When managers have a fragmentary vision of the company, a complete vision is replaced by a dangerously myopic partial vision, which does not consider the interaction between different management areas and therefore between different variables to be governed and risks to manage. Therefore, transfer pricing policies implemented by ignoring the economic aspects of business, valuing exclusively the fiscal ones, can lead to:

- anomalies in the distribution of liquidity within a corporate group, using transfer prices for the purpose of artificially allocating liquidity between the subsidiaries;

- anomalies in the definition of the costs of subsidiaries, because they are artificially constructed costs. The circumstance, ultimately, means a detrimental decrease in the general level of market competition.

Furthermore, instrumental plans for the reallocation of profits at a transnational level, using the transfer pricing tool, can be implemented in the context of company restructuring, normally accompanied by a redistribution of values between the companies involved (Pavone, 2016). Also, the studies carried out by the OECD (2010) highlight how such operations often lend themselves to profit shifting phenomena, connected to the formal allocation of risks and functions, or to the transfer of intangibles, in privileged or reduced tax jurisdictions, with consequent erosion of the tax base for the subsidiaries resident in countries subject to higher taxation. A concrete sign of this danger in Italy is represented by the acquisition of investments in Italian companies by foreign investors before corporate reorganization operations. Once they have entered the new "reorganized" group, the newly acquired Italian investments are exposed to profit shifting actions, due to the possibility of "having" "favorable" jurisdictions.

The national and international studies conducted on this topic allow us to outline a detailed picture of the symptomatology of alterations in transfer prices, precise risk factors considered by the tax authorities in the planning of their inspection activities. Thus, a study by OECD (2006) shows that the MNFs that apply pathological transfer pricing are significantly more predisposed to assume greater dimensions, are generally more profitable, are characterized by a higher level of indebtedness in their capital structure, are more engaged in cross-border operations with frequent recourse to foreign subsidiaries and they usually record a higher percentage of foreign-derived revenue as a part of the total assets.

Richardson, Taylor and Wright (2014), in a study on the characteristics of Australian companies under tax control, highlight the specific attributes of those companies that, through transfer pricing, try to transfer profits to the most favorable tax jurisdiction to minimize tax liability (Hamilton, Deutsch and Raneri, 2001): “levels of debt forgiveness, frequency of debt transfer within the corporate group, numbers of interest-free loans, numbers/amounts of payments to group subsidiaries of non-monetary consideration in lieu of cash given without accompanying commercial justification, probability of inadequately-disclosed transfer-pricing support, non- disclosure of differences between inter-group interest rates charged and arm’s-length interest rates and/or nondisclosure of supporting commercial reasons for such differences”.

Newberry and Dhaliwal (2001) note that another risk factor is represented by the absence of suitable documentation to illustrate the infrastructure of intercompany transactions, a circumstance that raises the concerns of the tax authorities. According to Shackelford, Slemrod and Sallee (2007), the opportunities for tax avoidance due to transfer prices are greater among MNFs with high profit margins generated by intangible assets (for example, the pharmaceutical industry), because in general for intangible assets (for example, R & D) it is more difficult to establish a fair value.

Finally, Erle (2008) highlights the importance for the MNFs of having adequate internal control systems for the tax risks management; in parallel, from the perspective of the tax authorities, a strong governance structure of the tax variable reduces the probability that a company performs illegal tax acts (Pavone and Di Nunzio, 2018). According to Erle (2008), the tax risk management activity, including transfer pricing risk, belongs to the top management but under the ultimate responsibility of the board of directors, also responsible for the predominant tax culture in the company. In this regard, Richardson, Taylor and Wright (2014), note that companies with weaker tax control mechanisms usually have higher expenses for tax consultancy, due to the greater use of external auditors in order to compensate for the shortcomings of the internal system of tax risk control.

The right amount of taxes, with reference to the correct periods in which the earnings have matured, must be collected by the States. For this purpose, the tax authorities must use their powers with impartiality and judgment (Baurer, 2005). Among these powers, the tax audit, a more detailed procedure than other formal controls (OECD, 2006), takes the form of an examination of whether a taxpayer has correctly reported his overall tax debt (Mebratu, 2016). Kircher (2008) defines tax audit as an examination of the tax position of an individual or organization by the tax authorities in order to ascertain compliance with the laws and tax regulations applicable in a State.

In developing inspection activities, tax authorities in Italy have a certain degree of autonomy. More specifically, it is a matter of "technical" autonomy, that is, mainly referring to the identification and selection of the companies to be subjected to control, to the choice of the inspection module to be adopted in the specific case, to the identification of the control methods and the investigation tools (Figure 2).

In particular, the strategy for preventing and combating tax crimes relating to transfer pricing is essentially based on two fundamentals:

- identification of distinct macro-types of companies, with respect to which to carry out a differentiated analysis and control process;

- adoption of control methodologies that consider the different characteristics and peculiarities (typological and dimensional) of the economic reality and of the context in which it is inserted, as well as of the potential risks of transfer prices manipulation.

Figure 2

Logical procedure of Italian tax authorities

in the exercise of their technical autonomy

Source: author's elaboration

In the last few years, quantity and quality of tax controls for MNF have increased, not only in Italy and in the countries of the OECD area. Chan, Lo and Mo (2015) indicate that Chinese tax authorities have gained much experience and expertise in transfer pricing over the past two decades. As a result, transfer pricing controls have significantly increased; Sakurai (2002) sees cultural and methodological differences in the styles of actions of the tax authorities. For example, the IRS tends to rely more on disputes and cross-examination checks, while the UK tax authorities prefer informal agreements; Japanese tax authorities prefer a collaborative and constant interaction with MNFs staff. Regardless of style, it is certain that the correct management of transfer prices requires an intimate relationship between business and tax elements, determining an alignment of administrative and tax compliance with the company's strategic variables. For this reason, for the tax authorities of the single States, the tax audit procedures are of an extremely complex nature since they require a deep knowledge of the company and of the operations carried out by it. Sometimes, it is possible to find an exclusively fiscal approach to transfer pricing by the tax authorities, which does not consider business logic.

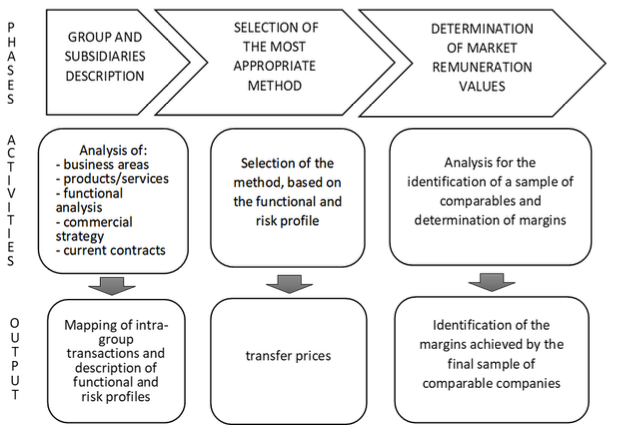

The tax audit activities on transfer pricing are characterized by extreme delicacy, also in consideration of the type of data and information, of potential strategic value, which tax inspectors are required to research and which are necessary for the purpose of adequate understanding of the corporate structure and of the corporate business. The ultimate objective of the tax audit is to identify the price that would have been agreed and applied for comparable transactions, comparing it with the price actually taken by the subsidiaries for the transaction being inspected (Eldenburg, Pickering and Yu, 2003). If the tax authority highlights the non-compliance with the "arm's-length principle", it can make an adjustment on the transfer prices of the resident company, with limited effect for tax purposes, without altering the contractual obligations between the subsidiaries. The control of transactions relating to transfer prices can be divided into three consecutive phases (Figure 3):

Figure 3

Phases of transfer pricing audit

Source: from Circular n. 1/2008 “Instruction on the tax audit activities”,

Vol. IV, Guardia di Finanza. Adaptation of the author.

The first phase relates to the description of the MFN, in all its corporate articulations, and to the understanding of the business that includes the analysis of the business areas, of the products and services offered, the functional analysis of the group companies, of the main contracts intercompany, distribution policies and, of course, transactions (both economically and financially). Functional analysis plays a crucial role in the economy of the entire inspection activity: it consists in the exact understanding of the function performed by a subsidiary in the production of the asset or in the realization of the service, considering resources used and risks assumed (EY, 2015), given that in an open and competitive market, the assumption of higher incomes is linked to the assumption of greater risks (market, inventory, product, financial, etc.). The objective of this phase is to correctly map intra-group transactions; then the choice of the most appropriate method for determining transfer prices will follow. On this point it should be noted that similar considerations motivate the decisions of MNFs and tax authorities in the selection of the most appropriate method, since both parties must assess: strengths and weaknesses of each method of determining transfer prices; appropriateness of the method in consideration of the controlled transaction through functional analysis; availability of information essential for the application of the method.

In a subsequent step a quantum-qualitative analysis of comparability is carried out, a concept that is pivotal to applying the arm's length tax principle (Arnold and McIntyre, 2002; Sikka and Willmot, 2010), aimed at identifying, through a skimming process progressive, a sample of comparable companies in terms of functional and risk profile, and to determine, consequently, the levels of market remuneration achieved by the comparables.

The results of many tax audit activities, at national and global level, have highlighted an aggressive approach by MFNs to the most current international tax issues, often distorting the logic of transfer pricing to favor the manipulation of tax bases. The process of defining transfer prices and its evolutionary dynamics over time has therefore assumed a strongly pragmatic nature, which derives from the pressing purpose of achieving the objective of minimizing the overall tax rate.

The theoretical framework outlined here contributes to increasing the literature on the subject of distinction between physiological and licit transfer pricing and fraudulent/pathological transfer pricing and to improve its analytical capacity, assuming the dual perspective of the companies that determine prices and the tax authorities that control the correctness of these prices.

To distinguish legitimate transfer pricing policies from those based on artificial shifts in taxable income, it is necessary to overcome the classic tension that has historically characterized relations between companies and tax authorities, laying the foundations for the construction of a constructive dialogue between the two parts of the tax obligation, giving substance to the principle of cooperative compliance of OECD matrix (2013). In this sense, in a modern and more equitable system of taxation, the tax authority must be able to go beyond the simple verification of the obligations of the tax payer (Biber, 2010), developing new and more advanced forms of audit, according to a respectful approach, which enhances taxpayers as subjects to assist in the fulfillment of tax obligations.

This research has some limitations. First of all, it overlooks the new challenges posed by the digital economy which offers further tax planning opportunities for MNFs, including through transfer pricing manipulations. Moreover, since it is a theoretical and descriptive analysis, it needs empirical confirmations on which future research can be developed.

However, it may have useful practical implications for both managers and tax offices, having helped to shorten the distance between their positions and hopefully to relax their relationships. For research and management studies and for professionals and practitioners, this analysis could constitute a theoretical basis for reflection, relevant for the purpose of identifying strategies for the correct management of transfer pricing dynamics, with positive implications also of reputational nature.

Abdallah Wagdy, M. (2004). Critical Concerns in Transfer Pricing and Practice, Praeger Publishers, London.

Anctil, R.M. and Dutta S. (1999). Negotiated Transfer Pricing and Divisional vs. Firm-Wide Performance Evaluation, The Accounting Review, 74(1), 87-104.

Arnold, B.J. and McIntyre, M.J. (2002). International Tax Primer, Kluwer Law International, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Baldenius, T., Melumad, N. and Reichelstein, S. (2004). Integrating Managerial and Tax Objectives in Transfer Pricing. The Accounting Review, 79(3), 591-615.

Bartelsman, E.J. and Beetsma, R.M.W.J. (2003). Why pay more? Corporate tax avoidance through transfer pricing in OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9-10), 2225-2252.

Baurer, L.I. (2005). Tax Administrations and Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries. Small and Medium Enterprise Department, World Bank.

Biber, E. (2010). Revenue Administration: Taxpayer Audit Development of Effective Plans, Technical Notes and Manuals, IMF, Fiscal Affairs Department.

Chan, K., Lo, A. and Mo, P. (2015). An Empirical Analysis of the Changes in Tax Audit Focus on International Transfer pricing. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 24, 94-104.

Clausing, K.A. (2003). Tax-Motivated Transfer Pricing and U.S. Intrafirm Trade Prices. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2207-2223.

Collins, J., Kemsley, D. and Lang, M. (1998). Cross-jurisdictional income shifting and earnings valuation. Journal of Accounting Research, 36(2), 209-229.

Conover T.L. and Nichols N.B. (2000). A Further Examination of Income Shifting Through Transfer Pricing Considering Firm Size and/or Distress. The International Journal of Accounting, 35(2), 189-211.

Dharmapala, D. and Riedel, N. (2013). Earnings shocks and tax-motivated income-shifting: Evidence from European multinationals. Journal of Public Economics, 97(C), 95-107.

Dean, J. (1955). Decentralization and Intracompany Pricing. Harvard Business Review, 33(July–August), 65-74.

Desai, M.A, Floey, C.F. and Hines, J.R. (2006). The Demand for Tax Haven Operations. Journal of Public economics, 90, 513-531.

Eden, L. (1983). Transfer pricing policies under tariff barriers. Canadian Journal of Economics, 16(4), 669-685.

Eldenburg, L. Pickering, J. and Yu, W. (2003). International Income-shifting Regulations: Empirical Evidence from Australia and Canada. The International Journal of Accounting, 38, 285-303.

Erle, B. (2008). Tax Risk Management and Board Responsibility. Tax and Corporate Governance, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 205-220.

Ernst & Young (2015). OECD releases final transfer pricing guidance on risk and recognition under Actions 8–10, EY Global Tax Alert Library, 13 october 2015.

Grabski, S.V. (1985). Transfer Pricing in Complex Organisations: A Review and Integration of Recent Empirical and Analytical Research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 4, 33-75.

Grubert, H. and Mutti, J. (1991) “Taxes, Tariffs and Transfer Pricing in Multinational Corporate decision Making”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(2), 285-293.

Guardia di Finanza. Instruction on the tax audit activities. Circular n. 1/2008. Vol. 4.

Hamilton, R.L., Deutsch R.L., and Raneri, J. (2001). Guidebook to Australian International Taxation, 7 th Edition 2001, Prospect, Sydney.

Heflebower, R.B. (1960). Observations on Decentralization in Large Enterprises. Journal of Industrial Economics, 9, 7-22.

Horst, T. (1971). The theory of multinational firm: optimal behaviour under different tariff and tax rates. Journal of Political Economy, 79, 1059-1072.

Hyde, C.E. and Choe C. (2005). Keeping two sets of books: the relationship between tax and incentive transfer prices. Journal of Economics, Management and Strategy, 14(1).

Hines, J.R. (1997). Tax Policy and the Activities of Multinational Corporations. In Auerbach, A.J. (Ed.), Fiscal Policy: Lessons from Economic Research. MIT Press, Cambridge, 401- 445.

Jacob. J. (1996). Taxes and transfer pricing: Income shifting and the volume of intrafirm transfers. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(2), 301-312.

Kant, C. (1988). Endogenous transfer pricing and the effects of uncertain regulation. Journal on International Economics, 24, 147-157.

Kircher, E.E. (2008). Enforced versus Voluntary Tax Compliance: The Slippery Framework. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(2), 210-225.

KPMG, (2005). Tax in the Boardroom: A Discussion Paper; KPMG, London, UK.

Levey, M.M. and Wrappe S.C. (2010). Transfer Pricing: Rules, Compliance and Controversy, Wolters Kluwer.

Li, D. and Ferreira, M.P. (2008). Internal and external factors on firms’ transfer pricing decisions: insights from organization studies. Notas Economicas, Junho, 23-38.

Mataloni, R.J. and Fahim-Nader, M. (1996). Operations of U. S. multinational companies: preliminary results from the 1994 benchmark survey. Survey of Current Business, 76(12), 11-37.

Mebratu, A.A. (2016). Impact of tax audit on improving taxpayers compliance: emperical evidence from ethiopian revenue authority at federal level. International Journal of Accounting Research, 2(12).

Morris, E. (2011). Transfer Pricing: History and Application of Regulations, available at http://www.claconnect.com/Tax/United-States-Transfer-Pricing-Tax-RegulationsArms-Length-Standard-Tangible-Intangible-Property.aspx.

Newberry, K. and Dhaliwal, D.S. (2001). Cross‐Jurisdictional Income Shifting by U.S. Multinationals: Evidence from International Bond Offerings. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(3), 643-662.

Novikovas, M. (2011). Evaluation of theoretical and empirical researches on transfer pricing. Ekonomika, 90(2).

OECD (2006). Strengthening Tax Audit Capabilities: General Principles and Approaches, Information note, October 2006, Tax Administration Compliance Sub-group, available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/46/18/37589900.pdf.

OECD (2010). Report on the transfer pricing aspects of business restructurings (Chapter IX of the transfer pricing guidelines).

OECD (2013). Co-operative Compliance: A Framework From Enhanced Relationship to Co-operative Compliance, Published on July 29, 2013.

Pavone, P. (2016). Transfer pricing e business restructuring. Implicazioni fiscali delle operazioni di riorganizzazione nei gruppi multinazionali. Novità fiscali, Centro di Competenze Tributarie della SUPSI-Università della Svizzera italiana, 7(9), 30-32.

Pavone, P. and Di Nunzio C. (2018). Evolution of the Internal Audit Function in the Management of Transfer Pricing. International Journal of Accounting and Taxation, 6(2): 14-22.

Prusa, T.J. (1990). An Incentive Compatible Approach to the Transfer Pricing Problem. Journal of International Economics, 28, 155-172.

Rego, S.O. (2003). Tax-Avoidance Activities of U.S. Multinational Firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20(4), 805-833.

Richardson, G., Taylor, G. and Wright, C. (2014). Corporate profiling of tax-malfeasance: A theoretical and empirical assessment of tax-audited Australian firms. eJournal of Tax Research, 12(2), 359-382.

Richardson, G., and Lanis, R. (2007). Determinants of the Variability in Corporate Effective Tax Rates and Tax Reform: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(6), 689-704.

Sakurai, Y. (2002). Comparing Cross-cultural Regulatory Styles and Processes in Dealing with Transfer Pricing. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 30, 173-199.

Shackelford, D.A., Slemrod, J., and Sallee, J.M. (2007), A Unifying Model of how the Tax System and Generally Accepted Accounting Principles affect Corporate Behavior; Working Paper, University of North Carolina and University of Michigan.

Sikka, P., and Willmot, H. (2010). The Dark Side of Transfer Pricing: Its Role in Tax Avoidance and Wealth Retentiveness. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(4), 342-356.

Slemrod, J., and Wilson, J.D. (2009). Tax Competition with Parasitic Tax Havens. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 1261-1270.

Smith, M. (2002). Tax and Incentive Trade-Offs in Multinational Transfer Pricing. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 17(3), 209-236.

Weichenrieder, A.J. (2009). Profit Shifting in the EU: Evidence from Germany, International Tax and Public Finance, 16(3), 281-297.

Wong, H., Nassiripour, S., Mir, R. and Healy, W. (2011). Transfer Price Setting in Multinational Corporations. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(9), 10-14.

Wray Bradley, E. (2015). Transfer pricing: increasing tension between multinational firms and tax authorities. Accounting & Taxation, 7(2), 65-73.

1. PhD Student. Department of Law, Economics, Management and Quantitative Methods. University of Sannio, Benevento. pietro.pavone@unisannio.it

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License