Vol. 41 (Issue 03) Year 2020. Page 15

MAYORGA, Juan A. 1; MORALES, Diana C. 2 & CARVAJAL, Ramiro P. 3

Received: 10/09/2019 • Approved: 14/01/2020 • Published 06/02/2020

ABSTRACT: This research analyzes the influential factors in female entrepreneurship in Latin America and Ecuador and identifies the gap in this activity between genders. Based on a review of specialized literature, Generalized Linear Models (GLM) are applied at an empirical level with data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and Doing Business for the period 2008-2015. The results show that factors related to social, cultural and economic aspects maintain a certain degree of incidence on female entrepreneurship in the countries analyzed. |

RESUMEN: Esta investigación analiza los factores influyentes en el emprendimiento femenino en Latinoamérica y Ecuador e identifica la brecha en esta actividad entre géneros. Se parte de una revisión de literatura especializada, a nivel empírico se aplica Modelos Lineales Generalizados (GLM) con datos del Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) y Doing Business para el periodo 2008-2015. Los resultados evidencian que factores relacionados con aspectos sociales, cultures y económicos mantienen cierto grado de incidencia sobre el emprendimiento femenino en los países analizados. |

The analysis of female entrepreneurship contributes to the understanding of both entrepreneurial activity and human behavior; in the last 30 years the role of women in economic and political activities has increased as well as the interest in studying this topic (Minniti & Naudé, 2010). Entrepreneurial activities bring positive effects on a society, the greater the practice, the greater the national economic growth (Ilie, Cardoza, Fernández, & Tejada, 2018). In addition, it emerges as an alternative procedure to the different circumstances that affects the society such as unemployment (Ortiz, 2017), or gaps in the labor market, where Teignier and Cuberes (2014) explain that generally women earn less, which involves fewer representation in some labors.

Davidsson, Low, and Wright (2001) state that research in female entrepreneurship is a contemporary necessity since it is in its early stages with several fields to develop. In Ecuador, this matter it is an incipient phenomenon given that it has not been a proliferation of studies in this area of research and the necessity of following the global trending of this subject has been detected.

The aim of this article it is to analyze the factors that influence female entrepreneurship in Latin America and in Ecuador, in order to identify the gaps in this activity with the masculine counterpart, using secondary data obtained from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and the Doing Business report from the World Bank in the period 2008 – 2015. Generalized Lineal Models (GLM) have been used to determine the significance of the environmental factors that women confront at the moment of starting off a new business. There limited number investigations that approach this subject and the published articles that are available are not free of discrepancy. For this reason, it is necessary to advance in the investigation of this field, which is complex and novel at both an economic and political level.

The relevance in the change of social status and political participation of entrepreneur women in the last four decades had provoked a growth in the academic interest of the topic (Minniti & Naudé, 2010). The first investigation on entrepreneurship reveals that there are not studies in which gender was considered one of the principal factors in the development of this activity (Jennings & Brush, 2013). In this regard, the first investigation developed by Schumpeter (1934) emphasized on this topic, in which special emphasis was given to entrepreneurial activities related to men (Goyal & Yadav, 2014). However, this situation took a turn in 1976 with the release of the first academic presented by Schwartz (1976), investigation that intended to establish particular characteristics, reasons, and attitudes that entrepreneurial women had in common (Greene et al.,2003). In spite of that, while the above mentioned article was the beginning for the development of this topic, more time was needed to highlight the need to go further on the topic. Years later, in Washington D.C, the first policy report appears, documenting the impediments that women confronted at the moment of beginning and developing their business, and actions by the government were requested to eradicate by the Organization for the Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 1998).

Also, Hisrich and O’Brien (1981) delivered a speech based on the article the woman entrepreneur as a reflection of the type of business, in which they explain the reason and characteristics of both women and their business, also the difficulties that they had to pass through. Goffee and Scase (1985) presented the first book that explains the experiences of women when they started their own business in the context of a society with gender inequity (Tyrkkö, 1986) and two further conferences were presented in both political and academic aspects (OECD, 1998). Overall, all these actions were considered as a preamble to the arise of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor reports, the same that in 2006 published the first Special Report for women, and on 2009, the first academic journal was launched titled International Journal of Gender Entrepreneurship, focused exclusively on this field.

Similarly, over the years research on this topic has been approached from different perspectives. Regarding to gender, it was initially proposed as a variable without demonstrating any specific theory (Greene, Brush & Gatewood, 2007). However, gender itself, explains the role, guidelines, behaviors, perspectives and functions that are socially assigned to men and women (Sarfaraz, Faghih & Majd, 2014). As time goes by an explanation was looked for to establish a theoretical framework to explain the differences between female entrepreneurship in relation to their male counterparts (Poggesi, Mari & De Vita, 2016). In this way, Fischer, Reuber and Dyke (1993) propose the liberal feminist theory, in which both genders possess the same capacity, and the social feminism, which manifested that both genders are not equal since women have specific demands, practices and values.

Nowadays world´s economy and democracy are facing the leadership and participation of both men and women (Bonanno, 2000). The act of entrepreneurship is not the same for each gender, some authors had demonstrated the differences in motivation, level of participation, ways of obtain funds, personality, among others.

In this context, we will begin by addressing the differences between men and women when starting a venture. Justo and DeTienne (2008) manifested that several studies showed that women start their own business not necessarily for economic purposes, but that their motivation force may be influenced by personal decisions, and family and environmental atmospheres. In addition, finding new job opportunities or better business opportunities can affect the way of how these decisions are taken. This is supported by Minniti and Naudé (2010), who explain that women are responsible of most of the household activities abandoned by men, which brings more flexibility and time for males to develop other activities. In the same line, Radović Marković (2009) states that female entrepreneurs are more realistic at the time of starting a business, and pretend to develop it with their relatives, using the resources obtained from this activity to give financial support to their children or family members (Terjesen & Amorós, 2010; Goyal & Yadav, 2014; Sarfaraz et al., 2014).

On the other hand, DeMartino and Barbato (2003) express that for men, motivations are based on obtaining economic resources and their professional development, with no major influence of family aspects in the achievement of these goals, like marriage or having kids; nevertheless, Cohoon, Wadhwa and Mitchell (2010) expose that men deal with the pressure of being the ones who traditionally provide economic support to the family.

Women have different motivations to start a business, which influence in setting up this activity. Empirical evidence has shown that women create less enterprises than men and are also owners or managers of fewer companies (Kim, 2007; Fuentes & Sánchez, 2010; Minniti & Naudé, 2010). Bosma and Kelley (2018) demonstrate this in the 2018/2019 GEM Global Report, in which they manifest that for seven women that are entrepreneurs there are 10 men in the same activity. The results show the existence of a gap in the entrepreneurial activity that come for different reasons, as will be explained later in the results.

Nonetheless, men and women present differences in their personality and it is important to distinguish which are the psychological characteristics of each. Fuentes and Sánchez (2010) establish that women stand out in attributes like decision making, creativity and self-confidence, whereas men present characteristics like optimism, tendency to develop difficult tasks, and daring to be entrepreneurs. In the same line, Navarro, Camelo and Coduras (2012), Chávez, Coral and Gallar (2018) point out in their study that both men and women possess high levels of self-reliance, differencing a lower ability of women to identify opportunities, related or not to entrepreneurship. Similarly, it is important to note that the above mentioned characteristics are consistent with those set out by McClelland (1961), who states that one of the primordial characteristics to be an entrepreneur it is the need of being noticeable, original, innovator, and long-term planificator to detect opportunities that can be exploited. It is important to highlight that there is no consensus between academics in this section, since, at the time of starting an entrepreneurial activity, few psychological and personal differences have been detected between the two genders (Pizarro 2008).

For the development of this study, several countries of the Latin American region have been considered, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay, emphasizing in Ecuador. The information obtained for this investigation was gathered from two sources. On one side, both Global Entrepreneurship Monitor instruments were used: The Adult Population Survey (APS) and the National Expert Survey (NES); on the other side, the information of the topic Starting a Business provided in the World Bank's Doing Business report was considered. It is worth mentioning that both databases information focused on women and their entrepreneurial activity. In addition, the variable Masculine Total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) has been considered to measure the gap between females and males in the above mentioned activity.

In this investigation, are considered twelve variables that measure the entrepreneurial activity of women in the mentioned nations are considered [Annex 1].

The statistic method selected to develop this study was the Generalized Lineal Models, which is a result of the expansion of the Lineal Models, the same that allows the usage of non-standard distribution errors (binomial for this studio) and non-constant variables (Cayuela, 2010). This method has been selected because it allows to compare two different scenarios: first, Latin America (excluding Ecuador), and then, Ecuador. In addition to the application of this statistical technique, the necessary tests were been run, such as Shapiro-Wilks (Sig.= 0,773 for Latin America and Sig.=0,58 for Ecuador), multicollinearity (all VIF values greater than 1 in all variables) and Omnibus test (Sig.= 0,00 for the GEM Model and 0,01 in the Doing Business Model) in the proposed scenarios.

It should be noted that although for most countries and variables the statistical information is complete, there are certain cases in which the data series were not complete, and it was not necessary to carry out a data reconstruction process, since Generalized Linear Models allow working with empty data, and the purpose of this study is also to reflect the reality of each nation.

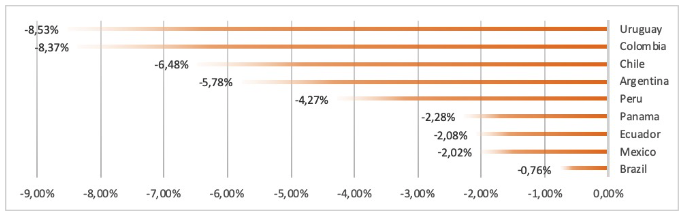

A first general observation referring to all countries in the 2008-2015 period is that the gap in the entrepreneurial exhibits a clear negative difference between the two main variables analyzed: Female TEA and Male TEA (Figure 1). This calculation is based on the normalized values of each nation, so it is a relative gap that allows us to observe the particular case of each country. The case of Uruguay or Colombia stands out, as they are the ones that present significant percentages (-8.53% and -8.37% respectively), while Ecuador presents a relative low value in comparison with other countries (-2.08%). In this respect Brazil highlights being the country with the lowest difference in this aspect on the region (-0.76%). Despite the fact that recent literature does not provide a generally accepted explanation for this gap (Markussen & Røed, 2017), there are certain factors that affect the gap presented by both genders at the time of starting an entrepreneurship, such as: education, salaries, employment sources, access to productive sectors, political and social representation and the capacity of negotiation at home as manifested by Cuberes and Teignier (2017). A possible explanation would be the cultural role heritage of both women and men (Markussen & Røed, 2017; Zambrano, Vázquez & Urbiola, 2019).

Figure 1

Gap in entrepreneurship. Women vs. Men, 2008-2015

Source: Authors’ own data based on GEM

The effects of this gap can be measured in different aspects. An example can be found by Cuberes and Teignier (2017) who study the macroeconomic effects on the gender difference in entrepreneurship in Latin America and the Caribbean, which concludes that only 25% of enterprises in this region are headed by women and are 3 times smaller than those led by men.

The effects of this gap can be measured in different aspects. An example can be found by Cuberes and Teignier (2017) who study the macroeconomic effects on the gender difference in entrepreneurship in Latin America and the Caribbean, which concludes that only 25% of enterprises in this region are headed by women and are 3 times smaller than those led by men.

In the Latin America scenario differences were found in variables such as: The fear of failure (F1) (Sig.= 0,02 < 0,05), starting a business due to opportunity (P1) (Sig.= 0,00 < 0,05), starting a business due to necessity (N1) (Sig.= 0,00 < 0,05), the perception of experts on the equality of knowledge and skills of men and women (AMR5) (Sig.= 0,002 < 0,05) and knowing somebody that has started a business in the last 2 years (C1) (Sig.= 0,00 < 0,05). In Ecuador there are differences in variables, such as: Starting a business in the next 6 months (O1) (Sig.= 0,01 < 0,05), having knowledge to start a new business (H1) (Sig.= 0,31 < 0,05) and the fear of failure (F1) (Sig.= 0,33 < 0,05) (table 1).

The detected variables in the running model are in tune with the results presented by different researchers. Even though entrepreneurs are known as individuals with capacities to assume and operate risks (Langowitz & Minniti, 2007), the fear of failure is a factor that, although affects both genres, seems to have a greater influence on women, as the results obtained by and Koellinger, Minniti and Schade (2013) explain.

Entrepreneurs can find different reasons to start a business, and according to the GEM methodology, it can be opportunity-based (P1) or necessity-based (N1) entrepreneurship. In this regard, Amorós (2011) highlights the presence of significative values in the detection of opportunities in Latin American countries. Although opportunity TEA, and necessity TEA values are similar in Latin America, in recent years there has been a growth in the need for income as an engine for business creation. Authors like Mares and Gómez (2006) explain it as a consequence of unemployment and lack of attractive wages, as confirmed by the study of Acs and Amorós (2008) that found a positive relation on their research of necessity-driven entrepreneurships and the Latin American Region. Also, Kelley et al. (2017) on GEM´s Special Report of women Entrepreneurship, state a woman has a 20% greater chance of start a business due to necessity than a man, regardless the level of economic development of the country.

Table 1

Parameter estimations for GEM model, Latin

America and Ecuador, 2008-2015 period

Region |

Wald´s Chi-square |

df |

Sig. |

Latin America (Interception) |

150066,8 |

1 |

0,000 |

F1 |

9,537 |

1 |

0,002 |

P1 |

37,287 |

1 |

0,000 |

N1 |

58,905 |

1 |

0,000 |

AM5 |

9,195 |

1 |

0,002 |

C1 |

20,797 |

1 |

0,000 |

(Scale) |

|

|

|

Ecuador (Interception) |

|

|

0,000 |

O1 |

0,012 |

1 |

0,001 |

H1 |

1,607 |

1 |

0,031 |

F1 |

4,527 |

1 |

0,033 |

(Scale) |

|

|

|

Dependent variable: TEA3

Model: (Interception), O1, H1, F1, NE1, P1, N1,

AM5, EFR, IE, C1, desplacement = AÑO

a. Maximum verisimilarity estimate.

b. Stated at zero because this parameter is redundant.

Source: Authors ‘own data.

In regard to the opinion of experts on the knowledge held by both men and women (AM5), there is a contrast with the results of the proposed model. This can be explained through the research of Kickul et al. (2008), where women perceive that they do not have the same level of skill as men when starting a business, although their self-efficacy has a greater effect on the entrepreneurial interest. Likewise, Mares and Gómez (2006) determine that the Economic Active Population (EAP) of Latin America does not usually consider themselves having enough abilities to start a business.

Finally, Escamilla, Caldera and Cruz (2014) stated that there is a positive relationship between a woman entrepreneur and the presence of role models in society. On the other hand, Merino and Vargas (2011) determine that women are less likely to enroll in social circles of entrepreneurs compared to their male peers; therefore, there is a lower percentage of women who know people who are starting or have already started a business (Minniti, 2010).

The Ecuadorian scenario results particular since it is a country where there is a high perception of opportunities to start a business among people (O1). The rate of this indicator has remained high in recent years; in this regard, Merizalde (2017) refers to this period as the ‘boom’ of entrepreneurship, due to the rise in TEA rates and subsequent consistence of it, (64,3 % in 2015, 43,6% in 2016 and 51.2% in 2017). This country stands out for having a higher average than the Latin American region for women entrepreneurs motivated by opportunity (Lasio et al., 2017). At the same time, it is interesting to find concordance with the study exposed by Lasio (2015) who highlights the existence of a relation between having the skills to undertake (H1) and distinguishing opportunities in the 61 studied countries (Kelley et al., 2015). Similarly, it should be noticed that in this country, the fear of failure is observed as a variable that can influence in the gap which stops entrepreneurial intention. This indicator is located in the average of the Latin American region.

The generated model is based on the data provided by the Doing Business report. In the Latin American Scenario, notable differences were found in the variables that measure the time (number of days) it takes a woman to start a business (Sig.= 0,037 < 0,05) and the cost of the procedures needed (according to the percentage of income per capita) (Sig.= 0,000 < 0,05). In Ecuador, only the time variable has influence in the development of the activity (Sig.= 0,000 < 0,05) (table 2).

Table 2

Parameter estimations for

the Doing Business model

Region |

Wald´s Chi- square (T) |

df |

Sig. |

Latin America 1 (Interception) |

1014949,054 |

1 |

0,000 |

AN1 |

0,257 |

1 |

0,612 |

AN2 |

4,350 |

1 |

0,037 |

AN3 |

12,863 |

1 |

0,000 |

Ecuador 1 (Interception) |

235505,38 |

1 |

0,000 |

AN1 |

1,819 |

1 |

0,177 |

AN2 |

13,922 |

1 |

0,000 |

AN3 |

0,218 |

1 |

0,640 |

Dependent variable: TEA3

Model: (Interception), AN1, AN2, AN3, desplacement = AÑO

a. Maximum verisimilarity estimate.

Source: Authors ‘own data.

In Latin America, the results show a negative presence of excessive paperwork and bureaucracy in some countries, which is somehow related to a higher cost for stablishing a company. This is reflected on the research exposed by Fuentelsaz and González (2015), Aguirre and Flores (2018), who detected a direct relation between a lower development of government entities and poor-quality business (those motivated by necessity) in the countries of the region. Similarly, Camargo, Ortiz Riaga, and Cardona García (2018) found that government aid does not promote to the entrepreneurship in American countries. In contrast, Baughn, Chua, and Neupert (2006) detected a positive relation between the normative support of government institutions and women's entrepreneurship in the 41 analyzed countries by the GEM project.

As for the variable cost for starting a company, the interpretation of the results obtained, according to the theoretical revision exposed, is ambiguous. On one hand, van Stel, Storey and Thurik (2007) have not found an influencing relation between the costs of constituting an enterprise and the nascent business. On the other hand, Asai et al. (2015) discover that the main obstacle in college students at the moment of being entrepreneur was having insufficient seed capital to cover the initial costs.

Ecuador it is not an exception, therefore it does not stand out in giving facilities to perform procedures for stablishing a company. By 2019, the average time for a woman to start a business was 48.5 days, high above the average of the region, which was 28.5 days (Doing Business, 2019). Under this scenario it is possible to interpret that the results obtained in the country explain the situation in a very brief way, and a clear relation between the factors taken into account by the model cannot be identified.

Female entrepreneurship activity has taken academic relevance in Latin America in recent years. This arises in response to the trend of the investigation of this topic worldwide, therefore there is a higher interest of researchers on studying this topic. While there are notable impediments for women in this area, such as cultural barriers, the fear of failure or difficulty in the access to credit, the entrepreneurship continues standing out as an alternative to generate resources, either for opportunity or necessity.

It should be mentioned that the two roles culturally imposed to women, regarding taking care of the household and performing professional and economical activities, are stablished as the main obstacles of female entrepreneurships on the region. The execution of these activities diminishes both time and energy aimed to their ventures, which results in a lower business performance. It is necessary to continue with the stimulation of entrepreneurial spirit in women in order to surpass the gap that exists with regarding to male entrepreneurial participation.

Due to the tendency mentioned on the interest on female entrepreneurship, Ecuador still differs in the fact that this phenomenon is, at an early stage of study, only finding investigations on an exploratory level. In these last two decades, this country has implemented certain programs and laws focused on women, on the regard of gender equality. Regarding entrepreneurship, there are laws though for citizens in general, without exclusively supporting female population. In this aspect, it is suggested that policy-makers promote laws and programs that encourage, develop and, support women in their economic activities. This will contribute to improving the economic and social development of the country, in two facets, on one hand, by narrowing the gap in participation in economic activities observed between both genders; and on the other, by improving the quality of life and well-being of women and their families.

To the Technical University of Ambato, Research and Development Department (DIDE). This article arises from the results of the research project entitled "Study for the Implementation of the Business Development Centre of the Faculty of Administrative Sciences", PFCA15.

Acs, Z. J., & Amorós, J. E. (2008). Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9133-y

Aguirre, J. C., & Flores, M. C. (2018). El emprendimiento en Latinoamérica. Un impacto diferenciable para el crecimiento económico entre países de la región. Revista Espacios, 39(32), 15. Retrived from: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n32/18393202.html

Amorós, J. (2011). El proyecto Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): Una aproximación desde el contexto latinoamericano. Academia. Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, (46), 1–15.

Asai, J., Flores, M., Montiel, M., Saavedra, M. L., & Tapia, B. (2015). Un ecosistema universitario de apoyo al emprendimiento femenino: El caso mexicano de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. In Emprendimiento femenino en Iberoamérica, 109–134. Colección Estudios RedEmprendia.

Baughn, C. C., Chua, B.-L., & Neupert, K. E. (2006). The Normative Context for Women’s Participation in Entrepreneruship: A Multicountry Study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00142.x

Bonanno, P. (2000). Women: The Emerging Economic Force. In Women Entrepreneurs in the Global Economy. Retrieved from https://numerons.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/17women-entrepreneurs-in-the-global-economy.pdf

Bosma, N., & Kelley, D. (2018). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Global Report (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association). Wellesley: Babson College.

Bosma, N., Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., Coduras, A., & Levie, J. (2008). GEM 2008 Data. Country Level Variable Descriptions. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Camargo, D. A., Ortiz Riaga, M. C., & Cardona García, O. (2018). Instituciones formales e informales en relación con el fenómeno emprendedor en América. Cuadernos de Administración, 34(61), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.25100/cdea.v34i61.6399

Cayuela, L. (2010). Modelos lineales generalizados (GLM). España: Universidad de Granadas.

Chávez, M. E., Coral, C., & Gallar, Y. (2018). Emprendimientos de mujeres y los entornos virtuales en Ecuador. Revista Espacios, 39(28), 11. Retrived from: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n28/18392834.html

Cohoon, J. M., Wadhwa, V., & Mitchell, L. (2010). Are Successful Women Entrepreneurs Different from Men? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1604653

Cuberes, D., & Teignier, M. (2017). Gender Gaps in Entrepreneurship and their Macroeconomic Effects in Latin America. https://doi.org/10.18235/0000931

Davidsson, P., Low, M. B., & Wright, M. (2001). Editor’s Introduction: Low and MacMillan Ten Years On: Achievements and Future Directions for Entrepreneurship Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870102500401

DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00003-X

Doing Business. (2019). Economy Profile of Ecuador. Retrieved from World Bank Flagship website: https://espanol.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/e/ecuador/ECU.pdf

Escamilla, Z., Caldera, D. del C., & Cruz, C. (2014). El emprendedor potencial: Identificación de oportunidades relacionadas con algunas variables del capital humano y social. Entreciencias: diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, 2(5), 245–261. http://dx.doi.org/10.21933/J.EDSC.2014.05.096

Fischer, E., Reuber, A. R., & Dyke, L. (1993). A Theoretical Overview and Extension of Research on Sex, Gender, and Entrepreneurship (Vol. 8). https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90017-Y

Fuentelsaz, L., & González, C. (2015). El fracaso emprendedor a través de las instituciones y la calidad del emprendimiento. Universia Business Review, (47), 64–81.

Fuentes, F., & Sánchez, S. (2010). Análisis del perfil emprendedor: Una perspectiva de género. Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 28(3), 1–28.

Goffee, R., & Scase, R. (1985). Women in charge: The experiences of female entrepreneurs (George Allen and Unwin.). London.

Goyal, P., & Yadav, V. (2014). To be or not to be a woman entrepreneur in a developing country? Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management, 2(2), 68–78.

Greene, P., Brush, C., & Gatewood, E. (2007). Perspectives on Women Entrepreneurs: Past Findings and New Directions. In M. Minniti (Ed.), Entrepreneurship. The Engine of Growth (Vol. 1). Connecticut: Praeger Perspectives.

Greene, P., Hart, M., Gatewood, E., Brush, C., & Carter, N. (2003). Women Entrepreneurs: Moving Front and Center: An Overview of Research and Theory.

Hisrich, R., & O’Brien, M. (1981). The woman entrepreneur as a reflection of the type of business. K.H. Vesper (Ed.), 54–67. Boston: Babson College.

Ilie, C., Cardoza, G., Fernández, A., & Tejada, H. (2018, February). Entrepreneurship and Gender in Latin America. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3126888 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3126888

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on Women Entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the Broader Entrepreneurship Literature? The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.782190

Justo, R., & DeTienne, D. (2008). Gender, family y situation and the exit event: Reassesing the opportunity-cost of business ownership. IE Business School Working Paper. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rachida_Justo/publication/23528730_Gender_family_situation_and_the_exit_event_reassessing_the_opportunity-costs_of_business_ownership/links/0c96052527a4ac9364000000/Gender-family-situation-and-the-exit-event-reassessing-the-opportunity-costs-of-business-ownership.pdf?origin=publication_detail

Kelley, D. J., Baumer, B. S., Cole, M., Dean, M., & Heavlow, R. (2017). Women’s Entrepreneurship 2016/2017 Report.

Kelley, D., Brush, C., Greene, P., Herrington, M., Ali, A., & Kew, P. (2015). GEM special report: Women’s entrepreneurship 2015. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Kickul, J., Wilson, F., Marlino, D., & Barbosa, S. D. (2008). Are misalignments of perceptions and self‐efficacy causing gender gaps in entrepreneurial intentions among our nation’s teens? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810871709

Kim, G. (2007). The analysis of self-employment levels over the life-cycle. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 47(3), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2006.06.004

Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2013). Gender Differences in Entrepreneurial Propensity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 75(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2011.00689.x

Langowitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). The Entrepreneurial Propensity of Women. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00177.x

Lasio, V. (2015). Emprendedoras. Retrieved from http://espae.espol.edu.ec/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/emprendedoras_espae.pdf

Lasio, V., Ordeñana, X., Caicedo, G., Samaniego, A., & Izquierdo, E. (2017). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Ecuador 2017. Retrieved from http://espae.espol.edu.ec/wp-content/uploads/documentos/GemEcuador2017.pdf

Mares, A. I., & Gómez, L. (2007). Hacia un diagnóstico latinoamericano para la creación de empresas con la aplicación del Modelo GEM 2006. Pensamiento y Gestión, 22, 85–142.

Markussen, S., & Røed, K. (2017). The gender gap in entrepreneurship – The role of peer effects. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 134, 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.12.013

McClelland, D. (1961). The Achieving Society. Princenton, NJ.: D. Van Nostrand Co.

Merino, M., & Vargas Chanes, D. (2011). Evaluación comparativa del potencial emprendedor de Latinoamérica: Una perspectiva multinivel. Academia. Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, (46), 38–54.

Merizalde, D. (2017). La mujer en los emprendimientos: Análisis Estadístico. In El emprendimiento en Ecuador. Visión y perspectivas (Nadia Aurora González Rodríguez, 54–87. Samborondón: Universidad ECOTEC.

Minniti, M. (2010). Female Entrepreneurship and Economic Activity. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.18

Minniti, M., & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the Patterns and Determinants of Female Entrepreneurship Across Countries? The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.17

Navarro, J. R., Camelo, M. del C., & Coduras, A. (2012). Mujer y desafío emprendedor en España. Características y determinantes. Economía industria, 383, 13–22.

OCDE. (1998). Women Entrepreneurs in Small and Medium Enterprises.

Ortiz, P. (2017). El discurso sobre el emprendimiento de la mujer desde una perspectiva de género. Vivat Academia, 0(140), 115. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.140.115-129

Pizarro, I. (2008). El reto de emprender en femenino. Retrieved from www. gipuzkoaemprendedora.net/boletines/es/isabel_pizarro_intervencion.pdf

Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2016). What’s new in female entrepreneurship research? Answers from the literature. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 735–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0364-5

Radović Marković, M. (2009). Women Entrepreneurs: New Opportunities and Challenges. New Delhi: Indo-American Books.

Sarfaraz, L., Faghih, N., & Majd, A. (2014). The relationship between women entrepreneurship and gender equality. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 2(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-7316-2-6

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development (Harvard University Press). Cambridge.

Schwartz, E. (1976). Entrepreneurship: A new female frontier. Journal of Contemporary Business, 47–76.

Teignier, M., & Cuberes, D. (2014). Aggregate Costs of Gender Gaps in the Labor Market: A Quantitative Estimate. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2405006

Terjesen, S., & Amorós, J. E. (2010). Female Entrepreneurship in Latin America and the Caribbean: Characteristics, Drivers and Relationship to Economic Development. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.13

Tyrkkö, A. (1986). Book Reviews: Robert Goffee & Richard Scase: Women in Charge. The Experiences of Female Entrepreneurs. London 1985, 153 pp. Acta Sociologica, 29(3), 274–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169938602900310

van Stel, A., Storey, D. J., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The Effect of Business Regulations on Nascent and Young Business Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9014-1

World Bank. (2019). Custom Query. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from Doing business website: https://espanol.doingbusiness.org/es/custom-query

Zambrano, S., Vázquez, A., & Urbiola, A. (2019). Empresas familiares, emprendimiento y género. Cinco problemáticas para el análisis regional. Revista Espacios, 40(22), 11. Retrived from: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a19v40n22/19402212.html

Variable |

Code |

Description |

Measurement unit |

Source |

Female TEA |

TEA3 |

Total Business Activity Index [TEA] 20XX. Number of adult females [18-64 years] per 100 participating in a start-up enterprise, in a young enterprise or both |

Percentage of every 100 surveyed enterprises that are start-ups or nascent (0-3 years) |

GEM APS |

MALE TEA |

TEA2 |

Total Business Activity Index [TEA] 20XX. Number of adult males [18-64 years] per 100 participating in a start-up enterprise, in a young enterprise, or both |

Percentage of every 100 surveyed enterprises that are start-ups or nascent (0-3 years) |

|

KNOW SOMEBODY |

C1 |

Percentage of all women, yes on item [July 20XX]: Do you know anyone who has started a business in the last two years? |

Percentage answered with alternative YES through Dichotomous Question: Yes or No |

|

6-MONTH OPPORTUNNITY |

O1 |

Percentage of all women, yes on item [July 20XX]: In the next 6 months will there be good opportunities to start a business in the area where you live? |

Percentage answered with alternative YES through Dichotomous Question: Yes or No |

|

SKILSS |

H1 |

Percentage of all women, yes on item [July 20XX]: Do you have the knowledge, skill and experience necessary to start a new business? |

Percentage answered with alternative YES through Dichotomous Question: Yes or No |

|

FEAR OF FAILURE |

F1 |

Percentage of all women, yes on item [July 20XX]: Fear of failure would prevent you from starting a new business? |

Percentage answered with alternative YES through Dichotomous Question: Yes or No |

|

BUSINESS DUE TO OPPORTUNNITY |

P1 |

Total Business Activity Index [TEA] 20XX. Number of female adults [18-64 years] for every 100 participating in a start-up enterprise, a young enterprise or both who state a reason for OPPORTUNITY. |

Percentage of every 100 adult women surveyed started a business due opportunity |

|

BUSINESS DUE TO NECCESITY |

N1 |

Total Business Activity Index [TEA] 2009. Number of female adults[18-64 years] for every 100 participating in a start-up business, a young business or both who state a reason for NECESSITY. |

Percentage of every 100 adult women surveyed started a business due necessity |

|

(SUPPORT FOR WOMEN)IN MY COUNTRY... |

AM |

Subjective assessment by national experts, surveyed by the GEM, of the aspects that encourage female entrepreneurship. |

Likert scale (1 = totally false, 5 = totally true) |

GEM NES |

OPENING A BUSINESS - PROCEDURES - WOMEN (NUMBER) |

AN1 |

"Procedures - Women (number)" records all the procedures needed for five women entrepreneurs to set up and manage a local limited liability company. |

It considers two types of limited liability company. Both businesses are identical in all respects, except that one is owned by five married women and the other by five married men. The score obtained in each sub-indicator is the average of the scores obtained in each of the components for both companies. |

DOING BUSINESS (WORLD BANK) |

OPENING A BUSINESS - TIME - WOMEN (DAYS) |

AN2 |

The "Time - Women (calendar days)" captures the average duration that business formation experts indicate is necessary for five women entrepreneurs to complete all the procedures required to start and operate a business with minimal follow-up and no additional payments. |

It captures the average duration, which lawyers with expertise in company formation or notaries consider in practice to be necessary to complete the required procedures, with minimal follow-up before public bodies and without making unofficial payments. |

|

OPENING A BUSINESS - COST - WOMEN (% OF PER CAPITA INCOME) |

AN3 |

"Cost - Women (% of per capita income)" is the total cost required for five women entrepreneurs to complete the procedures for incorporating and operating a business as a percentage of the per capita income. |

It is recorded as a percentage of the economy's per capita income and includes all official fees and fees for legal or professional services that are required by law or that are commonly used in practice. |

Source: Bosma, Acs, Autio, Coduras

& Levie (2008) and World Bank (2019)

1. Research Scholar. Faculty of Administrative Sciences. Technical University of Ambato. juan_andres_3096@hotmail.com

2. Doctor of Economic Development and Innovation. Professor of Faculty of Administrative Science. Technical University of Ambato. dc.moralesu@uta.edu.ec

3. Doctor of Economics and Business Management. Professor of Faculty of Administrative Science. Technical University of Ambato. ramiropcarvajal@uta.edu.ec

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License