Vol. 40 (Number 35) Year 2019. Page 7

OTERO Gómez, María C. 1 & GIRALDO PÉREZ, W. 2

Received: 26/06/2019 • Approved: 02/10/2019 • Published 14/10/2019

ABSTRACT: The objective of this article is to establish the impact of the value of the brand as a determinant of the intention to purchase and repurchase products through the analysis of the two segments: children and young people. This is a quantitative study, whose hypothesis contrast was made with a sample of 431 individuals. The results show that an adequate strategy to generate brand loyalty provides benefits for the company regarding purchase indicator, which suggests a better financial performance along with by business sustainability. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo de este artículo es establecer el impacto del valor de la marca como determinante de la intención de compra y recompra de productos a través del análisis de dos segmentos: niños y jóvenes. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo, cuya hipótesis se contrastó con una muestra de 431 individuos. Los resultados demuestran que una estrategia adecuada para generar lealtad a la marca proporciona beneficios para la empresa en cuanto a indicadores de compra, lo que sugiere un mejor desempeño financiero junto con la sostenibilidad del negocio. |

Brand equity is considered a differentiating element of a product or company performance in relation to the competition. From the supply perspective, the creation of strong brands and the improvement of their equity comprises, nowadays, a priority line of action for companies (Iglesias et al. 2002), since it is an intangible asset that provides higher income and increases sales. Hence, those aspects are highly important for commercial management, mainly in the construction of a new project, because every time a product is developed, the way to create a brand that consumers can trust is also paved.

During entrepreneurial processes, that is, during the detection of opportunities and the creation of organizations to seize them (Freire, 2012), it is necessary to learn to build, protect and maintain brand equity. Even once a solid brand has been established, the implementation of strategies must continue to maintain its value for both the consumer and the other market players. Examples of Colombian brands that have managed to survive over time and for several generations are: Chocoramo, in the candy category; Alpina, in the dairy category; and Totto, in the briefcases and backpacks category, along with other companies.

Some researchers have conceptualized that these results are achieved when consumers prefer a certain brand over the one that the competition offers. The explanation of this relationship, according to González et al. (2011), is that the purchase intention is preceded by high brand equity in the mind of the consumer; likewise, when there are repeated preferences for the same product, loyalty to the brand arises. Thus, loyalty becomes a positive attitude towards the brand and an effective repurchase intention (Shahrokh et al. 2013).

Accordingly, this study was conducted based on the question “Does brand equity have the capacity to generate purchase and repurchase intentions?” in order to help the consolidation of the innovative product sales resulting from entrepreneurship in a competitive environment, so that business results are sustainable over time.

The target group for this research focuses on the consumer who has the purchasing decision and power, and who becomes the main player in the consumption of products and brands. Therefore, the consumer is an important link between the entrepreneur, his company and its longevity. Two segments, whose characteristics were adjusted to the definitions of purchase intention and repurchase intention, were used. The first one is children, made up of potential customers for brands; the second one is young people, characterized not only by influencing purchase decisions, but by making their own decisions regarding the consumption of products.

This paper is organized as follows. In the initial part, the literature review, the hypotheses and the methodology developed during the research process are described. Next, the most significant findings of the empirical study are explained. Finally, the conclusions are presented together with the possible repercussions in commercial management. Likewise, the aspects that were not addressed in the research are described, which allows the proposal of new topics of study.

Brands have been considered as one of the most representative assets in current management, hence the importance of designing strategies that lead to their positioning. However, brands alone do not have the capacity to achieve this, since they require products with greater perceived value for consumers, which provides a greater competitive advantage for the organizations that own the brands (De Oliveira & Spers, 2018).

Thus, the brand-product relationship has the challenge of generating trust among consumers in such a way that it can face the characteristic risks of market forces. A strong brand must be able to resist the strategies designed by the competition in terms of prices, quality, quantity, variety and service; so, its ultimate goal is to make consumers loyal to the products offered by the company (Brunello, 2018). Additionally, the symbolic value that a brand represents in its target segment must be considered, because it is usual for consumers to find relationships that connect the functional and emotional aspects of the brand (Yang et al. 2018). In other words, a brand must have unique characteristics that differentiate it from rival brands.

Accordingly, the American Marketing Association (AMA, 2017) defines brand as "name, term, sign, symbol or design, or a combination of them intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of other sellers". This concept highlights the role of a brand as a differentiating element that is why its strategic value has been studied by various disciplines and sciences.

In the field of business, at the end of the 20th century, the term differentiation that took on great importance, mainly in the United States, emerged. In this respect Levitt (1980) proposes that there is no such thing as commodities and that all goods and services are differentiable through a brand. In the words of Trout (2001), differentiation is key to the survival of any company in a competitive world where consumers can choose from dozens of brands and products.

This draws the inference that there is a convergence of important authors towards the competitive advantages offered by the differentiation at the company or product level, and that this differentiation is achieved through the positioning of a brand. Aaker (1991); Hoeffler & Keller (2003); Kapferer (2008) agree that the efforts made by organizations in the construction of a brand provide advantages in the market. Some of them are: legal protection for products through trademark registrations, greater price differential over other products, increase in loyalty and degree of influence in purchasing decisions.

Therefore, the brand must be considered and valued as a business strategy. The term brand equity appeared at the end of the last century. Leuthesser (1988) defines it as the degree to which the single name of the brand adds value to the offer, and although to date no single measurement model has been established, it is clear that several authors, including Aaker (1991); Agarwall & Rao (1996); and Kim et al. (2008) show that the treatment in their measurement is multidimensional and its approach is based on the consumer.

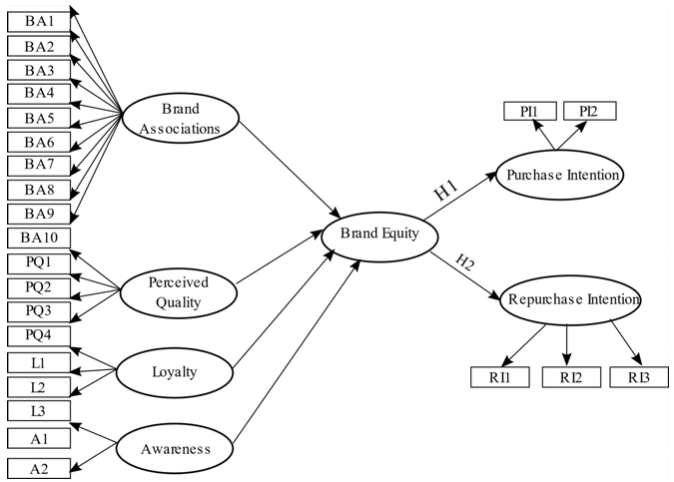

This work of research defines brand equity according to the multidimensional construct proposed by Aaker (1991) since he has been one of the pioneering authors in the study of the subject. Also, scientific literature, through multiple investigations carried out in different fields, has empirically corroborated the manifest relationship between the dimensions of brand equity and value granted by the consumer. It is essential to approach the concepts of brand associations (BA), perceived quality (PQ), loyalty (L) and awareness (A), all addressed from the perspective of the consumer.

It is the buyer's prediction about which company he will select to make a purchase (Turney & Littman, 2003). This is a very valuable concept, mainly in the performance of commercial management, because it helps managers identify the feasibility of expanding the portfolio of products offered to the market. However, it is a rather complex process because it involves the study of behavior, perceptions and attitudes of consumers. In addition, internal and external motivations influence the purchasing process, including preferences, price, quality, service, commercial establishment, on-line platform, and after-sales assistance, among others.

This study considers that children through their influence can persuade parents in the intention to purchase certain brands. There are previous studies that relate the purchasing behavior of the child consumer with the brand equity variable, (McGale et al. 2015; Meirira, 2017). Based on these contributions, the first hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Brand equity perceived by the child consumer has a positive and direct influence on the purchase intention.

One dimension of brand equity is loyalty, which triggers the repurchase intention of the consumer. Oliver (1997) stated that loyalty is an ingrained commitment to repurchase a preferred product or service consistently in the future, despite situational influences and marketing efforts that have the potential to cause a changing behavior. Varga et al. (2014) consider that it is possible to carry out a repurchase by establishing and managing relationships with customers through the offer adaptation of the organizations and through the constant provision of value for the client. Reichheld & Sasser (1990) argue that it is economically more profitable to improve the repurchase intentions of current customers than to constantly look for new customers.

Consequently, business strategies should aim at consumers to continue buying the product and become usual consumers of the brand, so in this research young people are expected to be responsible for repurchasing a brand as a result of their loyalty. Previous researches have verified the relationship between brand equity and repurchase intentions (Lin et al. 2015; Pather, 2017). As a result of the previous discussions, the second hypothesis is formulated:

H2: There is a significant and positive relationship between the dimensions of brand equity and repurchase intentions in the young segment.

Based on the hypothetical approaches described before, the testing of the following model is intended (Fig. 1):

Figure 1

Contrast model

This research had a correlational quantitative approach; hence, an intentional non-probabilistic sample was used. To develop this study, a total of 431 surveys were conducted in two measurements to different age groups. To determine the purchase intention in the children segment, 125 surveys were undertaken by children between 10 and 12 years old. These surveys were conducted in their schools with the approval of parents and the academic and administrative authorities of each educational institution. Likewise, in order to determine the repurchase intention of young people, 306 university students of programs related to administrative sciences responded to surveys in their classrooms. In all cases, the questionnaires were administered personally and answered in the presence of the researcher and the professor.

The brand equity variable had a reflective-formative second-order multidimensional treatment, while the purchase and repurchase intention variables were treated as one-dimensional variables.

The questionnaire shown in Appendix A was designed from the translations and adaptations of different authors such as:

• Brand associations (BA) : Lassar et al. (1995); Aaker (1996) and Netemeyer, et al. (2004).

• Perceived quality (PQ): Pappu et al. (2005 and 2006).

• Loyalty (L): Yoo et al. (2000).

• Awareness (A): Aaker 1996.

• Purchase intention (PI): Wang et al. (2013); Alavi et al. (2016).

• Repurchase intention (RI): Yoo et al. (2000) and Netemeyer, et al. (2004).

The response to each item was graded on a Likert scale with a range from (1) "In total disagreement" to (5) "In total agreement".

As a preliminary step to the verification of both hypotheses, the validity and reliability of the proposed model was evaluated through the use of the Partial Least Square approach, it was chosen because its use is adequate for the treatment of reflective-formative second-order variables, and it is a less restrictive technique in the distribution of data, which is appropriate when part of the sample is children younger than 12 years of age.

In order to corroborate the validity of the measurement instrument, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out by checking the measurements of all the indicators in the first stage, as shown in Table 1. Subsequently, the second order model was constructed as described in Table 2.

Table 1

Convergent validity and reliability

of the measurement scale

Variable |

Indicator |

Load |

Value |

p-value |

FC |

AVE |

Cronbach's alpha |

Brand equity |

BA1 |

0,915 |

76,407 |

0,000 |

0,938 |

0,835 |

0,901 |

BA2 |

0,913 |

77,721 |

0,000 |

||||

BA3 |

0,913 |

74,162 |

0,000 |

||||

BA4 |

0,886 |

67,257 |

0,000 |

0,932 |

0,776 |

0,903 |

|

BA5 |

0,892 |

64,236 |

0,000 |

||||

BA6 |

0,816 |

24,143 |

0,000 |

||||

BA7 |

0,925 |

103,882 |

0,000 |

||||

BA8 |

0,945 |

114,288 |

0,000 |

0,973 |

0,922 |

0,958 |

|

BA9 |

0,968 |

194,796 |

0,000 |

||||

BA10 |

0,968 |

192,146 |

0,000 |

||||

PQ1 |

0,874 |

46,656 |

0,000 |

0,921 |

0,746 |

0,886 |

|

PQ2 |

0,876 |

38,017 |

0,000 |

||||

PQ3 |

0,896 |

60,066 |

0,000 |

||||

PQ4 |

0,806 |

34,929 |

0,000 |

||||

L1 |

0,849 |

39,407 |

0,000 |

0,884 |

0,718 |

0,804 |

|

L2 |

0,875 |

55,928 |

0,000 |

||||

L3 |

0,818 |

30,886 |

0,000 |

||||

A1 |

0,777 |

23,616 |

0,000 |

0,899 |

0,641 |

0,860 |

|

A2 |

0,784 |

23,870 |

0,000 |

||||

A3 |

0,841 |

35,250 |

0,000 |

||||

A4 |

0,795 |

31,576 |

0,000 |

||||

A5 |

0,804 |

23,058 |

0,000 |

||||

Purchase intention |

PI1 |

0,914 |

26,318 |

0,000 |

0,907 |

0,830 |

0,796 |

PI2 |

0,908 |

20,128 |

0,000 |

||||

Repurchase intention |

RI1 |

0,932 |

100,581 |

0,000 |

0,941 |

0,842 |

0,906 |

RI2 |

0,929 |

86,507 |

0,000 |

||||

RI3 |

0,892 |

61,486 |

0,000 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, 2018

-----

Table 2

Convergent validity and reliability of

the second order measurement scale

Formative Construct |

Formative Indicator |

Weighs |

t-value |

p-value |

VIF |

Brand equity |

Brand Associations (BA) |

0,375 |

4,765 |

0,000 |

1,858 |

Perceived Quality (PQ) |

0,501 |

2,601 |

0,010 |

1,341 |

|

Loyalty (L) |

0,794 |

4,798 |

0,000 |

1,085 |

|

Awareness (A) |

0,449 |

2,266 |

0,024 |

1,258 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, 2018.

The next step was to verify the fulfillment of the values for the loads according to the proposal of Bagozzi & Yi (1988); for weights, according to the ranges of Sellin & Keeves (1994); for composite reliability, according to the recommendation of Chin (1998); Steenkamp & Van (1991); for the AVE, according to Fornell & Larcker (1981); for the VIF value according to Belsley (1990); and for Cronbach's Alpha according to Nunnally (1978). After all values were verified, it was evident that there is adequate internal consistency, reliability and convergent validity, so the hypothesis testing was made.

In order to measure the predictive goodness of the dependent constructs, the calculation of the Explained Variance (R2) of each dependent variable whose result, according to Falk & Miller (1992), must be at least 0,1 was used. The value obtained, shown in Table 3, confirms its relevance in this study.

Table 3

Explained variance (R2)

Dependent variable |

R2 |

Purchase intention (PI) |

0,238 |

Repurchase Intention (RI) |

0,444 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, 2018.

The results shown in Table 4 demonstrate compliance with the hypotheses proposed, H2 shows greater intensity (β = 0,666, p <0,001) and H1 shows less intensity (β = 0,466, p <0,001).

Table 4

Hypothesis contrast

Hypothesis |

Standardized β |

t-value |

p-value |

|

H1 Brand equity -> Purchase Intention |

0,466 |

*** |

6,073 |

0,000 |

H2 Brand equity -> Repurchase Intention |

0,666 |

*** |

16,514 |

0,000 |

*** Value t> 3,310 (p <0,001); ** Value t> 2,586 (p <0,01); * Value t> 1,965 (p <0,05); ns: not significant.

Source: Prepared by the authors, 2018.

This research demonstrated that brand equity measured through its variables, namely, loyalty, perceived quality, awareness and brand associations, have a direct and positive relationship with the purchase intention and generate repurchase processes. Consequently, both H1 and H2 are confirmed. However, it is evident that the predictive capacity and the intensity of the relationship with the repurchase behavior (H2) are higher than with the initial purchase (H1). These results are similar to those obtained by Huang et al. (2014) and by Lin et al. (2015) since the appreciable characteristics of the different brands increase the repurchase probability.

The results of each formative dimension of the brand equity variable allow them to be sorted gradually from highest to lowest and reveal that it has a higher positive effect compared to the consumers intentions, like this: loyalty with a weight of 0,794, followed by perceived quality with 0,501 and awareness with 0,449; finally, the lowest effect is obtained by the brand association dimension with a weight of 0,375.

The inference is that consumer loyalty is mainly supported by the perceived quality of the product, which is related to the findings of Nam et al. (2011) who demonstrated that quality captures the functional aspects of the brand and leads to consumer satisfaction. This generates a great influence on loyalty and, accordingly, increases the brand equity perceived by the consumer.

In the context of business and entrepreneurship, these results are consistent with the findings of Reichheld & Sasser (1990) because they can be interpreted as the opportunity to take advantage of dissatisfaction in the market by launching a novel product. In order for this product to live long and to last over time, it is necessary to generate sales, which is achieved thanks to awareness of a brand in the mind of a consumer, i.e., positioning and subsequent loyalty.

In the case of the companies that serve the studied segments and considering the repurchase intention importance in the results, there is a great opportunity for them, since they will be able to expand the product lines. This represents the possibility of increasing its market share and a greater subsequent brand presence. The brand itself becomes a strategy for companies to be financially sustainable with products that stand out and last in the market.

The results suggest that the segment of young consumers showed repurchase intention of products they have used since childhood. That is why companies must build brand awareness and loyalty as well as its value over time. A company that offers the market an innovative product must be accompanied from the beginning by a brand positioning process, so its durability will allow obtaining the loyalty of consumers.

The findings allow establishing some implications for business management. Firstly, the entrepreneurial process with an innovative product and its launch to the target market is recommended once the respective brand registration is available. This is done to take advantage of being the owner of the brand and thus exploit it commercially with the purpose of gradually increasing its awareness. Secondly, entrepreneurs should carry out brand management by business units, positioning each one independently, which will facilitate to undertake a new venture in the eventuality of a failure of a product and / or brand of another business unit. Lastly, it is convenient that companies constantly conduct studies to know the opinions of consumers about the perceived quality of their products. In this way they will have valuable information to develop marketing strategies based on innovation, but according to the needs of their customers.

Finally, this research has limitations. The first one is that the study was carried out in Villavicencio, which is why the generalization of the results to an entire country should be avoided. The second one is that due to the interest of the authors, attention was focused on the brand as a strategy that helps business sustainability, assuming that the entire process took the previous steps to determine the business opportunity and product launch.

As a result of this research, more questions than answers regarding consumer behavior arise. Undoubtedly, this brand equity topic can be considered as a future line of research with young people based on the role of marketing in social networks. As for children, due to their interest in making purchases, it would be advisable to explore the topic of financial education, associating it with the saving of money intended for their consumption.

The authors are grateful for the financial support received from the Colombia Scientific Program and its Passport to Science component of the Government of Colombia, through the allocation of partially forgivable educational credits.

Aaker, D. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York, USA: The free press.

Aaker, D. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102-120.

Agarwall, M.K. & Rao, V.R. (1996). An empirical comparison of consumer-based Measures of brand equity. Marketing Letters, 7(3), 237-247. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00435740

Alavi, S. A., Rezaei, S., Valaei, N., & Wan, W. K. (2016). Examining shopping mall consumer decision-making styles, satisfaction and purchase intention. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 26(3), 272 - 303.

Alfaro, M. (2004). Temas claves en Marketing Relacional. Madrid, España: McGraw-Hill/Interamericana Editores.

American Marketing Association(2017). Retrieved from https://www.ama.org/resources/Pages/Dictionary.aspx?dLetter=B&dLetter=B

Bagozzi, P. R. & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation model. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16(1), 74-94. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02723327

Belsley, D. A. (1990). Conditioning diagnostics: collinearity and weak data in regression. New York, USA: John Wiley and Sons.

Brunello, A. (2018). Brand equity in sports industry. International Journal of Communication Research, 8(1), 25-30.

Chin, W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 7–17.

Chiu, C., Huang, H., Weng, Y., & Chen, Ch. F. (2017). The roles of customer-brand relationships and brand equity in brand extension acceptance. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 18(2), 155-176.

Correia, L. S. & Miranda, G. F. (2010). Calidad y satisfacción en el servicio de urgencias hospitalarias: análisis de un hospital de la zona centro de Portugal. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 16 (2), 27-41.

De Oliveira, R. O. & Spers, E. E. (2018). Brand equity in agribusiness: Brazilian consumer perceptions of pork products. Journal of Business Administration, 58 (4), 365-379.

Falk, R. F. & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. Akron, USA: University of Akron Press.

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50.

Freire, A. (2012). Pasión por emprender. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Aguilar.

González, H. E., Orozco, G. M. & De la Paz, B. A. (2011). El valor de la marca desde la perspectiva del consumidor. Estudio empírico sobre preferencia, lealtad y experiencia de marca en procesos de alto y bajo involucramiento de compra. Contaduría y Administración, 235, 217-239.

Hoeffler, S. & Keller, K. (2003). The marketing advantages of strong brands. Journal of Brand Management, 10(6), 421-445.

Huang, C., Yen, S., Liu, C., & Chang, T. (2014). The relationship among brand equity, customer satisfaction, and brand resonance to repurchase intention of cultural and creative industries in Taiwan. International Journal of Organizational Innovation (Online), 6(3), 106 - 120.

Iglesias, A. V., Vásquez, C. R. & Del Río, L. A. (2002). El Valor de marca: Perspectivas de análisis y criterios de estimación. Cuadernos de Gestión, 1 (2), 87-102

Jiang, Y., & Wang, C.L. (2006). The impact of affect on service quality and satisfaction: the moderation of service contexts. Journal of Services Marketing, 20/4, 211-218.

Kalafatis, S.P., Remizova, N., Riley, D. & J. Singh, J. (2012). The differential impact of brand equity on B2B cobranding. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 27(8), 623-634.

Kapferer, J. (2008). The new strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term. Philadelphia, USA: Kogan Page.

Kim, E.Y., Knight, D.K. & Pelton, L. E. (2008). Modeling brand equity of a U.S. Apparel brand as perceived by generation Y consumers in the emerging Korean market. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 27 (4), 247-258.

Lassar, W., Mittal, B. & Sharma, A. (1995). Measuring Customer-based Brand Equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 11-19.

Leuthesser, L. (1988). Defining, measuring, and managing brand equity. Conference Summaries Marketing Science Institute, pp. 88-104. Retrieved from https://www.msi.org/conferences/summaries/defining-measuring-and-managing-brand-equity/

Levitt, T. (1980). Marketing success through differentiation – of anything, Harvard Business Review January. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1980/01/marketing-success-through-differentiation-of-anything/ar/1

Lin, A. Y., Huang, Y. & Lin, M. (2015). Customer-based brand equity: The evidence from china. Contemporary Management Research, 11(1), 75 - 93.

McGale, L., Harrold, J., Halford, J. & Boyland E. (2015). Does the presence of brand equity characters on food packaging affect the taste preferences and choices of children? Appetite, 87, 390.

Meiria, E. (2017). Ekuitas Merek dan Keputusan Pembelian: Studi Pada Konsumen Anak Usia Sekolah Dasar di Kota Depok. Esensi: Jurnal Bisnis dan Manajemen, 7(1), 111-130.

Mowen, J.C. & Minor, M.S. (2011). Consumer behavior: A framework. Upper Saddle River, USA: Prentice Hall.

Nam, J., Ekinci, Y. & Whyatt, G. (2011). Brand equity, brand loyalty and consumer satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1009–1030.

Netemeyer, R.G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J. & Wirth, F. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57, 209-224.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York, USA: McGraw Hill.

Oliver, R.L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioural perspective on the customer. New York, USA: McGraw Hill.

Pappu, R., Quester, P.G. & Cooksey, R. W. (2005). Consumer‐based brand equity: improving the measurement – empirical evidence. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(3), 143-154.

Pappu, R., Quester, P.G. & Cooksey, R.W. (2006). Consumer-based Brand Equity and Country-of-origin Relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 40 (5/6), 696-717.

Pather, P. (2017). Brand equity as a predictor of repurchase intention of male branded cosmetic products in South Africa. Business & Social Science Journal, 2(1), 1-23.

Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser, W. E. (1990). Zero defects: Quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68(5), 105-111.

Sellin, J. B., & Keeves, J. P. (1994). Path analysis with latent variables. The international encyclopedia of education. Oxford Pergamos, 8, 4352-4359.

Shahrokh, Z.D., Oveisi, N. & Timasi, S.M. (2013). The effects of customer loyalty on repurchase intention in b2c e-commerce- a customer loyalty perspective. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(6), 636-644.

Steenkamp, J. B. & Van Trijp, H. (1991). The use Lisrel in validating marketing constructs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8, 283-299.

Supphellen, M. (2000). Understanding core brand equity: Guidelines for in-depth elicitation of brand associations. International Journal of Market Research, 42(3), 319–338.

Trout, J. (2001). Diferenciarse o morir: cómo sobrevivir en un entorno competitivo. Madrid, España: McGraw Hill.

Turney, P. D. & Littman, M. L. (2003). Measuring praise and criticism: Inference of semantic orientation from association. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 21 (4), 315-346.

Varga, A., Vujičić, M. & Dlačić, J. (2014). Repurchase intentions in a retail store – exploring the impact of colours. Econviews, XXVII, Br. 2, pp. 229-244.

Wang, Y.S., Yeh, CH. H. & Liao, Y.W. (2013). What drives purchase intention in the context of online content services? The moderating role of ethical self-efficacy for online piracy. International Journal of Information Management 33(1), 199-208.

Yang, D., Lu, Y. & Sun, Y. (2018). Factors influencing Chinese consumers’ brand love: evidence from sports brand consumption. Social behavior and personality, 46(2), 301-312.

Yoo, B., Donthu, N. & Lee, S. (2000). An Examination of Selected Marketing Mix Elements and Brand Equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (2), 195-11.

Questionnaire

Dimension |

Item |

Brand Associations (BA) |

BA1. The brand (XX) offers me what I want / need |

BA2. The brand (XX) has a good quality-price ratio |

|

BA3. The brand (XX) provides a high value in relation to the price that must be paid for it |

|

BA4. The brand (XX) has personality |

|

BA5. The brand (XX) is associated with a symbol of prestige BA6. When I use the brand (XX) I make a good impression on others |

|

BA7. I have a clear picture of the type of people who use the brand (XX) |

|

BA8. I trust the company that makes the brand (XX) |

|

BA9. The company that makes the brand (XX) is admirable |

|

BA10. The company that makes the brand (XX) has credibility |

|

Perceived Quality (PQ) |

PQ1. (XX) offers very good-quality products |

PQ2. The products of (XX) offer good results |

|

PQ3. The products of (XX) are reliable |

|

PQ4. The products of (XX) have excellent characteristics |

|

Loyalty (L) |

L1. I consider myself a consumer loyal to the brand (XX) |

L2. When I'm going to buy (Category) (XX) is my first choice |

|

L3. I would not buy other brands of (Category) if (XX) was available in the physical establishment |

|

Awareness (A) |

A1. I know the brand (XX) |

A2. The brand (XX) looks familiar |

|

A3. I've heard about the brand (XX) |

|

A4. When I think of (Category), (XX) is one of the brands that comes to mind |

|

A5. I can quickly recognize the symbol or logo of (XX) in front of other competing brands |

|

Purchase Intention (PI) |

PI1. I would like to buy the brand (XX) |

PI2. If I have the money, I will buy one (XX) |

|

Repurchase Intention (RI) |

RI1. I will continue paying for products of the brand (XX) |

RI2. I intend to continue buying the brand (XX) in the future |

|

RI3. I would continue buying brand products (XX) instead of any other brand available |

1. Profesora Asistente y Líder del grupo de Investigación Dinámicas de Consumo de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. E-mail: motero@unillanos.edu.co

2. Magíster en Mercadeo. Profesor Asistente adscrito a la Escuela de Administración y Negocios de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. E-mail: wgiraldo@unillanos.edu.co