Vol. 40 (Number 7) Year 2019. Page 7

Francoise V. CONTRERAS 1; Juan Carlos ESPINOSA 2

Received: 20/10/2018 • Approved: 18/01/2019 • Published 04/03/2019

3. Dark and Bright Leaders: Are they really two opposite sides?

4. Followers and workplace in the dark side of leadership

ABSTRACT: In the last decades, most of the literature related to leadership has been oriented to describe leadership from a positive approach, showing its favourable effects. However, the dark side has been understudied. The aim of this study is to analyze the dark side of leadership in relation to its supposed counterpart bright side. We conclude that there is a thin edge between both sides, discussing the need for more empirical research to identify their limits, convergences and shared features. |

RESUMEN: En las últimas décadas, la mayor parte de la literatura relacionada con el liderazgo se ha orientado a describir el liderazgo desde un enfoque positivo, mostrando sus efectos favorables. Sin embargo, el lado oscuro ha sido poco estudiado. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar el lado oscuro del liderazgo en relación con su supuesto lado brillante. Concluimos que hay un estrecho borde entre ambos lados, discutiendo la necesidad de desarrollar más investigación empírica que permita identificar sus límites, convergencias y características compartidas. |

Leadership is a term commonly viewed from a positive perspective. It is understood as something that companies need to achieve high standards of performance promoting their growth and competitiveness. In this same line, the notion of being a leader has been mainly related to CEOs, managers and supervisors that influence favorably on others (followers/subordinates) to achieve organizational goals (Macarie, 2007). Under this framework, most of the scientific literature developed in this field of knowledge has shown leadership as a “positive force” as it was called (Bligh, Kohles, Pearce, Justin, & Stovall, 2007). However, there is another face of leadership, a dark side less studied but not because of that less important. During the last decades important findings have demonstrated that the so-called dark side of leadership is a complex phenomenon that should be understood more deeply due to supposed negative effects on employees, companies and society in general. Sometimes it is not easy to identify these leaders in organizations because contrary to what might be expected, some effective leaders who fit well within the characteristics of a transformational or charismatic leader may have a hidden dark side, hidden even for themselves. The purpose of this paper is to discuses this phenomenon from the personal characteristics and organizational effects according to the literature.

The dark side of leadership is the other face of the traditional leadership notion, which had acquired different nominations such as aversive leadership or the destructive force in organizations (Bligh et al., 2007), destructive leadership (Einarsen, Aasland, & Skogstad, 2007), abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), and toxic leaders (Lipman-Blumen, 2008) among others. As can be seen, this approach can be applied to the person that exerts leadership in organizations and to the conditions or processes that this type of leaders generate and promote. From a wide perspective, dark managers or supervisors are destructive and use harmful strategies to influence their subordinates or followers (Krasikova, Green, & LeBreton, 2013). These leaders tend to be abusive and have hostile both verbal and non-verbal behaviors (Tepper, 2000).

Understanding why people behave like this in organizations implies to consider the individual factors that underlie such behaviors. As any human behavior, leadership and the way to be exerted involves the whole individuality of the person. This is to say, the emotions, the cognitions, the perceptions about itself and about others, previous experiences, values, knowledge, competences, self-esteem and personality traits among others. From this individual approach, the personality of leaders has received more attention.

Although some authors have related dark leaders to an antisocial personality disorder (Goldman, 2006), most researchers in this area have studied the personality traits of these leaders with the so-called dark triad of personality which is composed by three traits: 1) narcissism, 2) Machiavellianism and 3) psychopathy (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Narcissism is a trait characterized by a sense of superiority, arrogance, lack of sensitivity, vanity, grandiosity, hostility, absence of empathy (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), elevated level of self-admiration, self-absorption, entitlement and hostility (Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Because of this trait narcissistic individuals usually keep poor interpersonal relationships mainly due to the absence of empathy and the tendency to manipulate others seeking their own interest (Judge, Piccolo, & Kosalka, 2009). According to Alvinius, Johansson and Larsson (2016), narcissistic individuals tend to exert a negative leadership in any organization and even in organizations where conditions are optimal. Likewise, leaders with this trait are more likely to overestimate their own effectiveness as a leader increasing the risk for companies (Grijalva, Harms, Newman, Gaddis, & Fraley, 2015) which could be explained by their elevated level of self-love and their beliefs that they are unique, special and worthy of admiration, they feel different from others and view others as inferiors to themselves (Judge et al., 2009). Narcissistic leaders tend to participate in conversations where their own self-image is enhanced, however they are very skilled to adapt their self-centered nature to keep a positive impression in front of others (Leary & Kowalski, 1990).

Machiavellianism on its part is a trait related to manipulation, leaders with this characteristic feel the necessity to exert control over others and abuse their power (Judge et al., 2009). Machiavellian leaders give little importance to moral and pro-social values in their acts (Becker & O'Hair, 2007) and tend to be dishonest to keep their power showing a kind of emotional detachment towards others (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Machiavellians leaders aspire to reach high positions in companies and desire to have a formal authority resulting in a high motivation to become a leader, something that could become their personal goal. Machiavellian leaders are prone to think strategically and have the ability to handle power in companies or political organizations (Mael, Waldman, & Mulqueen, 2001).

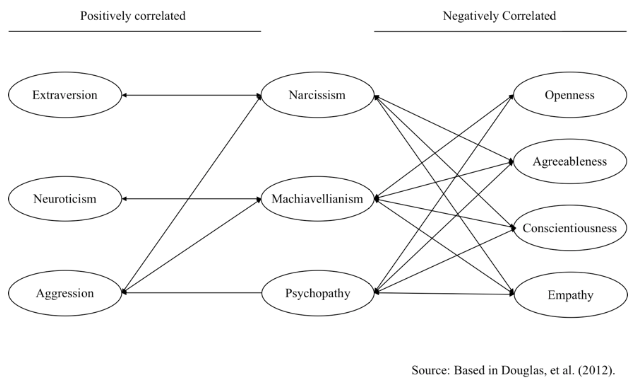

Finally, the psychopathy trait is related to the inability to genuinely experience emotions, egocentrism, impulsiveness, irresponsibility, lack of empathy or guilt, to the tendency to manipulate and avoidance of following social norms (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Because of these features, these leaders are emotionally unstable and sometimes are engaged with antisocial behaviors showing an absence of empathy joined with high impulsiveness (Douglas, Bore, & Munro, 2012). Psychopathy is particularly harmful because the individual that possesses this trait seems to be sincere and charismatic but internally they lack a stable personality structure. Furthermore, previous findings have demonstrated that the dark triad is related to other well-founded models of personality such as the five-factor model (Douglas et al., 2012). (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Relationships among dark triad and personality factor

Despite the existence of clear characteristics that differentiate dark leaders from bright leaders, there are some closely related features that are hardly distinguishable. These traits are empirically overlapped but theoretically separable (Hart & Hare, 1998) and can appear in some dark and non-dark leaders in an independent way. In fact, some bright leaders could have in some extent some of these traits. According to recent meta-analytics, narcissism is related to the emergence of leadership in general terms and maybe due to this people tend to be more extroverted (Grijalva et al., 2015). Additionally, there is some evidence although limited, that psychopathy is also associated to leadership behaviors (Westerlaken, & Woods, 2013), in fact, leaders with this trait could not be recognized as psychopaths and usually reach high-level positions (Mullins-Sweatt, Glover, Derefinko, Miller, & Widiger, 2010). Likewise, Machiavellian leaders seem to have the natural power to influence their followers to achieve their personal goals although they abuse their position or formal authority given by the organization (Goldberg, 1999).

In some cases, dark leaders pretend to be transformational and seem to be charismatic but contrary to this “bright style of leadership”, they are dominant, aggressive, exploit, threat others, punish and manipulate their followers for their own personal interests (Conger, 1990; Sankowsky, 1995). Contrary to transformational leadership, these leaders are less likely to produce positive effects such as inspiration, guidance and mentoring on their followers (Barrett et al., 2009). Thus, it is interesting to notice that such behaviors related to the dark triad can be present quite often in companies, however, people in the workplace could not able to recognize these patterns of behaviors as harmful. In this way, it is likely to find companies where their leaders show high superiority and dominance (linked to narcissism), they are eloquent, charismatic and manipulative (Linked to Machiavellianism), showing insensibility, impulsiveness and an absence of empathy (Linked to psychopathy) (Boddy, 2010; Galperin, Bennett, & Aquino, 2010; Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006).Therefore these leaders tend to be perceived by others as good communicators, creative and with a high ability to think strategically (Babiak, Neumann, & Hare, 2010). It is because of this that these leaders can effectively function in different occupations and usually reach high-level positions without being recognized as psychopaths (Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2010).

Recently Tourish (2013) asserted that transformational leadership could have two sides: a bright one and a dark one. Li and Yuan (2017) suggests that the effects of these two sides are opposed and that the negative effect of the dark side will suppress the positive effect of bright side. The main premise that supports this idea is that charisma, the main feature of transformational leadership is potentially prone to boastfulness, self-admiration, excessive power, self-importance, self-admiration, superiority, self-centeredness, with the need for success and the denial of criticism (Villiers, 2014). Following this same line, Palmer, Walls, Burgess, and Stough (2001) asserted that these leaders could be called pseudo-transformational because of their ability to handle their emotions and those of others for obtaining personal goals according to their own convenience. This ability has been demonstrated as significantly correlated to Idealized Influence and Inspirational Motivation behaviors, other central characteristics of transformational leadership. These findings could demonstrate that it would be wrong to put a marked limit between the bright and the dark face of leadership as well as its effectiveness on organizational results.

Regarding these last issues there is an important debate because the results obtained from empirical researches have not been conclusive. To consider that bright traits are good whereas dark traits are bad seems to be a simple approach taking into account that the effect of personality traits on organizations is quite complex (Smith, Hill, Wallace, Recendes, & Judge, 2018). Thus, some authors have found that the organizational outcomes of dark leaders tend to be poor because they lack management skills which may lead them to exercise a passive leadership causing an important damage not only for the companies that they lead but to their employees producing huge emotional and economic costs (Barrett et al., 2009). In addition, an organizational environment characterized by cynicism joined to scarce support from the leaders, produces more emotional fatigue in employees, diminishing their loyalty to the company (Akbaş, Durak, Cetin, & Karkin, 2018).

Following this same line, high levels of Machiavellianism have shown a positive relationship to supervisor abuse (Wisse and Sleebos, 2016) and decreasing creativity in groups (Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Iskra-Golec, 2013). Likewise, abusive supervision by managers affects creativity in employees (Liu, Liao, & Loi, 2012). However, other studies have found that some traits of this triad could be favourable for organizations, except for psychopathy, which has demonstrated to be an important predictor of antisocial behavior (Paulhus & Williams, 2002) and the most destructive trait of the whole triad (McKee, Waples, & Tullis, 2017).

For example, high levels of narcissism as a trait of the dark side of leadership could be adaptive under certain circumstances (Petrenko, Aime, Ridge, & Hill, 2016). These leaders usually emerge in moments of uncertainty because they tend to be perceived as confident by the stakeholders, which help them to reach high positions (Smith et al., 2018). Contrary to what is expected, narcissistic leaders are usually involved in activities related to corporate social responsibility maybe because they receive attention by doing that and this makes them more influential. (Petrenko et al., 2016). Thus, despite their self-interest to achieve their own goals, narcissistic leaders may be beneficial to their organizations (Smith et al., 2018). Machiavellian leaders on their part are flexible and have the ability to manage successfully structured and non-structured tasks. They even could be perceived as charismatic by their followers (Drory & Gluskinos, 1980). In addition, they are able to develop strategies composed of a wide sort of influential tactics to make connections and achieve some type of power that allows them to acquire resources promoting the organizational goals (Dingler-Duhon & Brown, 1987).

Furthermore, some authors have demonstrated that the bright side is not always beneficial for organizations, in fact, high levels of “bright traits” in leaders, such as being extremely conscientious could in some situations negatively influence the organizational outcomes (Carter, Guan, Maples, Williamson, & Miller, 2015). Additionally, Volmer, Koch, & Göritz (2016) found that the dark triad of leadership has bright and dark sides that exert influence on the careers of employees and their perceived well-being. According to the results of this study, narcissism is the brightest trait of the dark triad because it positively affects the perception of success in the employees´ careers in both objective and subjective criteria, without negative effects on the well-being of the subordinates. On the other hand, leaders with Machiavellianism and psychopathy showed an adverse effect on the success on the career of the followers and their well-being (Figure 2). These results support previous findings where Machiavellianism and psychopathy were the darker traits of the triad (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2013).

Figure 2

Relationship among leader dark triad and follower’s work conditions.

So far there is not enough knowledge about the interaction between the bright and dark traits of personality (Smith et al., 2018), neither how the different combinations of the dark and bright traits are related to leadership behaviors nor their effects on employees and organizational outcomes. It is very important to conduct more research oriented to understand in a deep way the dark and bright sides of leadership (or gray scales?). Increasing our knowledge on this topic may have important implications for both researchers and practitioners.

Finally, it is important to consider the influence of these traits of personality to the nascent successful companies. In some cases, these traits that allow entrepreneurs being successful in their companies can become a source of destruction due to the individual needs of the entrepreneurs that can compromise the longevity of the company (Kets deVries, 1985). These internal needs involve the confrontation with risk, entrepreneurial stress and entrepreneurial ego among others (Kuratko, 2007). This issue should be studied more; the current knowledge about these personality traits and corporate success is scarce.

Leadership is a process that involves leaders and followers. Studying the dark side of leadership implies to understand it from the follower´s side, how the leaders’ behavior is supported. In other words, the emergence of leadership styles requires the follower´s dispositions. Thus, traits of leaders and followers can combine to produce a negative effect and so the dark side of leadership could affect the organizational outcomes. To have a dark follower could increase the devastating effect (Clements & Washbush, 1999). In this order of ideas, it is very important to consider that not all counter-productive behavior comes only from leaders and that there are followers with a negative trait (Clements & Washbush, 1999).

If there is something dysfunctional in the personality of leaders then we can expect that it also affects followers. Due to this, leadership is a dynamic process that involves the relationship between leaders and followers so it is very important to study the role of the followers in the dark side of leadership. Clements and Washbush (1999) asserted that followers could decrease the synergy produced in the interaction between leaders and followers. Furthermore, followers could in some way, desire and reinforce the practices of dark leaders although without being aware that these behaviors could be adverse. In this regard, McKee et al. (2017) found that the psychopathy of followers – not in Machiavellianism nor Narcissism - leads to the desire for dark leaders. According to this study, psychopathy is the strongest predictor of accepting the behavior of leaders with high traits of psychopathy. These findings point out the importance of studying the followers’ position regarding this dark leadership; something about which we do not have enough knowledge yet.

Regarding the workplace it can be asserted that negative leadership can be seen as a destructive way to lead. These leaders give priority to organizational goals they want to achieve even if these goals are destructive or are not coherent with the interests of the company (Krasikova et al., 2013). Although negative leadership could be seen as a result of the interaction between contextual and individual characteristics, it could be asserted that extremely greedy organizations are usually led by negative leaders (Alvinius et al., 2016). As a result, negative organizations are characterized by a lack of confidence in the organization, weak linkage between employees and their company, selfishness, tough stance towards workers, discrimination, bullying, anxiety, security risks, cuts in resources, over-demand in tasks and compromise the psychological and physical resources of employees among others (Alvinius et al., 2016).

Although it can be assumed that dark leadership exerts negative effects on organization outcomes and their employees showing a negative relationship with work success (Furnham, Trickey, & Hyde, 2012), although Judge and LePine (2007) asserted that some undesirable traits of the personality could have positive implications, in fact, some authors have found that these traits are positively related to leadership success (Bollaert & Petit, 2010; Ouimet, 2010; Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Recently Jonason, Wee, Li, and Jackson (2014) found that the dark triad traits involved psychological mechanisms that may be beneficial under some circumstances. As can be seen, this issue needs to be better understood because there is no academic consensus in this regard.

Finally, results show that perceptions of aversive or abusive leadership are negatively related to the job satisfaction of followers, (Bligh et al., 2007; Tepper, 2000; Bruck, Allen, & Spector, 2002) higher turnover, more psychological distress and more work-family conflict (Tepper, 2000), decreasing the employee work performance (Harris, Kacmar, & Zivnuska, 2007).

The dark side of leadership is a less common approach to leadership in the organizational field of knowledge. Due to its implications on employees, organizational processes and successful companies, this topic should be further studied providing empirical evidences. Supported in the literature, it can be asserted that the so-called “dark side” of leadership is not as simple as it was but on the contrary, it is a complex phenomenon, whose effects are not always completely negative. There is no academic consensus yet about the effects of negative leaders neither in companies nor employees. Likewise, as any process related to leadership, followers/collaborators and situations should be studied in order to understand the dark side of leadership because its emergence in companies and its effects depend on them.

It is interesting to notice that a more recent approach of this topic proposed that there is no clear line that divides the “dark” and “bright” sides of leadership but there is a blurry and thin edge. Thus, the dark side may have a brighter and darker side instead of being just black and white. This finding offers a new perspective that should be studied, considering these phenomena a scale of grays. In fact, transformational leadership considered one of the most “bright styles” of leadership could also have its own dark side and nobody in companies notices this negative connotation. Even more, in some cases these leaders have being called pseudo-transformational but in other cases they can be transformational with a dark side. This issue in particular should be studied deeply due to the current “popularity” of this leadership style in the business field.

According to the literature the dark traits are related in a natural way to the emergence of leadership, this being understood as an influential process. However, psychopathy seems to be the darker trait. Narcissism and Machiavellianism may have their own brighter side showing favorable effects related to the effectiveness of leadership. Nevertheless, Psychopathic and Machiavellian traits have a double fold that should be identified and controlled in both leaders and followers. Likewise, it’s important to identify which organizational conditions promote and support the dark side of leadership in order to diminish or avoid its negative effects.

In sum, studying leaders and their characteristics is still necessary, as well as to understand how these traits from the so-called dark triad of personality affect and are influenced by other organizational variables such as the personality of followers. (i.e. psychopathic followers tend to prefer darker leaders and followers with a high-power necessity tend to be Machiavellian for obtaining promotions). As it was documented there is a “dark triangle” (traits of leaders, characteristics of followers and environmental conditions) that support and maintain this leadership exerting influence on the followers, the organizational environment, the stakeholders in general, the outcomes of companies, the organizational success and society as a whole.

ALVINIUS, A., JOHANSSON, E., & LARSSON, G. (2016). Negative organizations: Antecedents of negative leadership. In: D. Watola & D. Woycheshin (Eds.). Negative leadership: International perspectives. Ontario (Canada): Canadian Defence Academy Press. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/mdn-dnd/D2-367-2016-eng.pdf

BABIAK, P., NEUMANN, C., & HARE, R. (2010). Corporate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 28, 174–193. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bsl.925

BARRETT, B., BYFORD, S., SEIVEWRIGHT, H., COOPER, S., DUGGAN, C., & TYRER, P. (2009). The assessment of dangerous and severe personality disorder: Service use, cost, and consequences. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(1), 120–131.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940802236864

BECKER, J., & O'HAIR, H. (2007). Machiavellians' motives in organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Communcation Research, 35(3), 246−267. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880701434232

BLIGH, M., KOHLES, J., PEARCE, C., JUSTIN, J., & STOVALL, J. (2007). When the Romance is Over: Follower Perspectives of Aversive Leadership. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(4), 528–557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00303.x

BODDY, C. (2010). Corporate psychopaths and organizational type. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(4), 300–312. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pa.365

BOLLAERT, H., & PETIT, V. (2010). Beyond the dark side of executive psychology: Current research and new directions. European Management Journal, 28(5), 362–376. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.01.001

BRUCK, C., ALLEN, T., & SPECTOR, P. (2002). The relation between work–family conflict and job satisfaction: A finer-grained analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(3), 336–353. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1836

CARTER, N., GUAN, L., MAPLES, J., WILLIAMSON, R., & MILLER, J. (2015). The downsides of extreme conscientiousness for psychological well-being: The role of obsessive compulsive tendencies. Journal of Personality, 84(4), 510-522.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org /10.1111 /jopy .12177

CLEMENTS, C., & WASHBUSH, J. (1999). The two faces of leadership: Considering the dark side of leader-follower dynamics. Journal of Workplace Learning, 11(5), 170-176. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/13665629910279509

CONGER, J. (1990). The dark side of leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 19(2), 44–55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(90)90070-6

DINGLER-DUHON, M., & BROWN, B. B. (1987). Self-disclosure as an influence strategy: Effects of Machiavellianism, androgyny, and sex. Sex Roles, 16(3-4), 109-123. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00289643

DOUGLAS, H., BORE, M., & MUNRO, D. (2012). Distinguishing the dark triad: Evidence from the five-factor model and the Hogan development survey. Psychology, 3(3), 237–242. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.33033

DRORY, A., & GLUSKINOS, U. M. (1980). Machiavellianism and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(1), 81−86. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.1.81

EINARSEN, S., AASLAND, M., & SKOGSTAD, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behavior: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 207–216. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

FURNHAM, A., TRICKEY, G., & HYDE, G. (2012). Bright aspects to dark side traits: Dark side traits associated with work success. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(8), 908–913. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.025

GALPERIN, B., BENNETT, R., & AQUINO, K. (2010). Status differentiation and the protean self: A social-cognitive model of unethical behavior in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 407–424. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0556-4

GOLDBERG, L. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. De Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Editors.). Personality psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg (The Netherlands): Tilburg University Press.

GOLDMAN, A. (2006). Personality disorders in leaders: Implications of the DSM IV-TR in assessing dysfunctional organizations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(5), 392–414. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610673942

GOLEC DE ZAVALA, A., CICHOCKA, A., & ISKRA-GOLEC, I. (2013). Collective narcissism moderates the effect of in-group image threat on intergroup hostility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(6), 1019-1039. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032215

GRIJALVA, E., HARMS, P., NEWMAN, D., GADDIS, B., & FRALEY, R. (2015). Narcissism and leadership: A meta‐analytic review of linear and nonlinear relationships. Personnel Psychology, 68(1), 1-47. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/peps.12072

HARE, R. & NEUMANN, C. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 217–246.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452

HARRIS, K., KACMAR, K., & ZIVNUSKA, S. (2007). An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 252–263. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.007

HART, S., & HARE, R. (1998). Association between psychopathy and narcissism: Theoretical views and empirical evidence. In: E. Ronningstam (Ed.). Disorders of narcissism: Diagnostic, clinical, and empirical implications. Washington DC (USA): American Psychiatric Press.

JONASON, P., WEE, S., LI, N., & JACKSON, C. (2014). Occupational niches and the Dark Triad traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 119–123. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.024

JUDGE, T., & LEPINE, J. (2007). The bright and dark sides of personality. In: J. Langan-Fox, C. Cooper, & R. Klimoski (Eds.). Research Companion to the Dysfunctional Workplace. Cheltenham (UK): Elgar.

JUDGE, T., PICCOLO, R., & KOSALKA, T. (2009). The bright and dark sides of leader traits: A review and theoretical extension of the leader trait paradigm. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(6), 855–875. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.09.004

KETS DE VRIES, M. (1985). The dark side of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 63(6), 160–67.

KRASIKOVA, D., GREEN, S., & LEBRETON, J. (2013). Destructive leadership: A theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1308-1338. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471388

KURATKO, D. (2007). Entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(4), 1–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130040201

LEARY, M., KOWALSKI, R. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34−47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34

LI, J., & YUAN, B. (2017). Both angel and devil: The suppressing effect of transformational leadership on proactive employee’s career satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 65, 59-70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.008

LIPMAN-BLUMEN J. (2008). Following toxic leaders: In search of posthumous praise. In: R. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.). The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations. San Francisco, CA (USA): Jossey-Bass.

LIU, D., LIAO, H., & LOI, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187-1212. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0400

MAEL, F., WALDMAN, D., & MULQUEEN, C. (2001). From scientific careers to organizational leadership: Predictors of the desire to enter management on the part of technical personnel. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(1), 132−148. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1783

MCKEE, V., WAPLES, E., & TULLIS, K. (2017). A Desire for the Dark Side: An Examination of Individual Personality Characteristics and Their Desire for Adverse Characteristics in Leaders. Organization Management Journal, 14(2), 104-115. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2017.1325348

MULLINS-SWEATT, S., GLOVER, N., DEREFINKO, K., MILLER, J., & WIDIGER, T. (2010). The search for the successful psychopath. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 554–558. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.010

OUIMET, G. (2010). Dynamics of narcissistic leadership in organisations. Towards an integrated research model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(7), 713–726. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011075265

PALMER, B., WALLS, M., BURGESS, Z., & STOUGH, C. (2001). Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730110380174

PAULHUS, D., & WILLIAMS, K. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

PETRENKO, O., AIME, F., RIDGE, J., & HILL, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 37(2), 262-279. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.2348

RAUTHMANN, J., & KOLAR, G. (2013). The perceived attractiveness and traits of the dark triad: Narcissists are perceived as hot, Machiavellians and psychopaths not. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.005

ROSENTHAL, S., & PITTINSKY, T. (2006). Narcissistic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 617–633. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.005

SANKOWSKY, D. (1995). The charismatic leader as narcissist: Understanding the abuse of power. Organizational Dynamics, 23(4), 57–72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(95)90017-9

SMITH, M., HILL, A., WALLACE, J., RECENDES, T., & JUDGE, T. (2018). Upsides to Dark and Downsides to Bright Personality: A Multidomain Review and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 44(1), 191-217. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317733511

TEPPER, B. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–191. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

TOURISH, D. (2013). The Dark Side of Transformational Leadership: A Critical Perspective. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 28(1), 369-370 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/DLO-12-2013-0098

VILLIERS, R. (2013). The Dark Side of Transformational Leadership: A Critical Perspective. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2512-2514.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.01.006

VOLMER, J., KOCH, I., & GÖRITZ, A. (2016). The bright and dark sides of leaders' dark triad traits: Effects on subordinates' career success and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 413-418. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.046

WESTERLAKEN, K., & WOODS, P. (2013). The relationship between psychopathy and the Full Range Leadership Model. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(1), 41-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.026

WISSE, B., & SLEEBOS, E. (2016). When the dark ones gain power: Perceived position power strengthens the effect of supervisor Machiavellianism on abusive supervision in work teams. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 122-126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.019

1. Full-time professor and director of research. School of Management, Universidad del Rosario. Bogotá-Colombia (South America). orcid.org/0000-0002-2627-0813 E-mail: francoise.contreras@urosario.edu.co

2. Full-time professor. School of Management, Universidad del Rosario. Bogotá-Colombia (South America) http://www.orcid.org/0000-0002-1643-2233 E-mail: juanc.espinosa@urosario.edu.co