Vol. 40 (Number 6) Year 2019. Page 25

MORALES, María J. 1; VITERI-SALAZAR, Oswaldo 2; OÑA-SERRANO, Alberto X. 3; MEJÍA, Kléber H. 4; DONOSO, Diego J. 5

Received: 18/10/2018 • Approved: 27/01/2019 • Published 18/02/2019

ABSTRACT: This article examines how stores that promote fair trade in the city of Quito are managed. It starts by contextualizing the fair trade movement. Then analyzes the current commercial conditions under which the stores operate. It ends by determining the existing relationship between these stores’ commercial management and their use of ICT. The final goal is to pose commercial management strategies based on ICT that would contribute to improving the position of these stores in the competitive market. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo examina cómo se gestionan las tiendas que promueven el comercio justo en la ciudad de Quito. Comienza por contextualizar el movimiento del comercio justo. Luego analiza las condiciones comerciales actuales bajo las que operan estas tiendas. Finaliza determinando la relación existente entre la gestión comercial de estas tiendas y su uso de TICS. El objetivo final es plantear estrategias de gestión comercial basadas en TICS, que contribuyan a mejorar la posición de estas tiendas en el mercado competitivo. |

The exchange of goods and services forms the economy basis. Currently, the relationships that govern trade and commerce are not equitable. They encourage inequality, disadvantaging underdeveloped countries and leaving them in an unfavorable competitive position in relation to stronger and more powerful international markets. International commerce exacerbates the differences between countries in the global North and South. Specifically, the northern tier countries control the parameters of international commerce. They are the leaders in marketing-related fields, sales, research, and development. They own the capital and control technological knowledge, thus positioning themselves for competitiveness and maximum benefit. This leaves the countries of the South as sources of raw materials and cheap labor (CECJ, 2011; McBurney, 2010). This inequitable situation generates consequences at the social level, such as an unjust distribution of wealth, social exclusion, and exploitation aimed specifically at women and children (Stenn, 2013), because the market is run by big multinational corporations that fail to return benefits to local communities (Becker & Arditi, 2006; Rojas, 2003). This dominance also has a heavy negative impact on the environment, including eradication of productive land, deforestation, water contamination, and destructive exploitation of natural resources (Calisto Friant, 2016). It is clear that the current development model based on economic self-interest, international dependence, and unequal commercial relationships does not work. Thus, it must look for new commercial arrangements.

With this background, fair trade, also known as reciprocal trade or solidarity trade, began as an emerging alternative movement within the current economic system. Fair trade is based on guaranteeing a fairer price for the producers of the South, as well as better working, social, and environmentally sustainable conditions. The main four Fair Trade networks (Fair Trade Labelling Organizations International (FLO), International Fair Trade Association (now World Fair Trade Organization or WFTO), Network of European Worldshops (NEWS!) and the European Fair Trade Association (EFTA)) officially defined the movement as a trading partnership based on dialogue, transparency, and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers” (Doherty, Smith, & Parker, 2015, p.11; Treviño, 2013, p.276; WFTO-FLO, 2013, p. 5). With that goal in mind, fair trade has been spreading and growing stronger throughout the world. It is becoming a global movement and a network of agency committed to responsible production and consumption. It is staking its position on different forms of production, trade, and consumption that place individuals and the environment at the crux of socio-economic development (Donaire, 2010). Having come this far, the main goal of the agents involved in fair trade is to strengthen the relationship between producer and consumer as they simultaneously alter the rules of the hegemonic capitalist market by their actions. The main agents of the fair trade movement include small producers (the system’s base), producer organizations, intermediary organizations dedicated to fair trade (such as importers and certifiers), stores that sell fair trade goods, and finally, consumers (Caritas, 2012; Ceccon Rocha & Ceccon, 2010). It should be pointed out that retail sites play a fundamental role in raising awareness about fair trade, since they constitute its most direct interface with the consumer. Stores are responsible for popularizing the underlying components of the fair trade value chain.

Having said that, in order to achieve their ideals of equality, justice, and solidarity, fair trade organizations govern themselves according to several important principles. These include a) paying a fair price for goods; b) no child labor or forced labor; c) no discrimination of any type; d) dignified working conditions; e) long-term trade relationships based on solidarity; f) fostering confidence and respect between producers and marketers; g) environmental stewardship; and h) consciousness raising among consumers (Coscione, 2013; Doherty, Davies, & Tranchell, 2013; Elfkih, Wannessi, & Mtimet, 2013; Lozano, 2011; Petljak, Štulec, & Zrnčević, 2015; Raynolds & Bennett, 2015; WFTO, 2013). It is important to point out that fair trade acknowledges, promotes, and protects the cultural identity and traditional ways of small producers as reflected in the design of handicrafts, food traditions, and related services (Fretel, Felipe, Villegas, & Reyes, 2009). Taking this into account, the movement has made multiple positive impacts, both social and economic, for small producers and their communities. Nevertheless, those involved in the fair trade movement still have challenges to meet. For example, fair traders want to change the trading conditions that govern the conventional market. The job of raising the awareness of consumers and creating strong local markets composed of productive solidarity networks is of vital importance. This is an important step in becoming a strong global movement. Another challenge for fair trade organizations is not only to survive but to distinguish themselves under current market conditions, which have been radically transformed by information technology (Beynon, 2014; Laudon & Laudon, 2012; O`brien & Marakas, 2012), yet without losing sight of the objectives and principles that guide fair trade.

In this respect, information and communications technology (ICT) not only would transform these organizations, but also greatly affect individual participants, societies, and the environment. ICT has the capability to change commercial relationships, consumer behavior, and the manner in which business is conducted. Joyanes (2015) defines ICT as “computer-based tools that people use to handle information within an organization” (p.5). In this sense, ICT encompasses a wide variety of tools that help one manage information in our current information-saturated environment. We should point out that ICT has a positive impact on a) improving productivity; b) opening global markets— thanks to the advantages e-commerce implementation creates; c) developing new business models; d) improving client relationships; e) automating services and processes; f) enabling agile decision-making and rapid response capability; g) improving internal and external communications; h) guiding precision in market and client information; and i) generating new strategies aided by digital marketing tools and strategies, and social network management (Dolci, Schwengber, Guilherme, & Gastaud, 2012).

Likewise, we assert that ICT is a set of tools that is basic to managing any commercial aspect of business. According to Herrero (2011), commercial management comprises those activities related to exchanges between business and the market. It is the last step of the productive process, by means of which business products penetrate the market that, in exchange, contributes economic resources back to businesses. Commercial management covers all steps from the business plan to the arrival of products to the consumer, including sales and marketing strategies and policies. By applying ICT, along with the tools and software to manage it, commercial activity becomes a value-added process for the client. Customer Relationship Management (CRM) can be seen as the most important information system for a business’s trade management.

Therefore, ICT is essential for digital marketing, also known as e-marketing. E-marketing rolls together the majority of applications for which business uses digital technology. These include Internet access, telecommunications networking, and digital technologies needed to fulfill the marketing objectives of the organization (Rodríguez, 2014). Nowadays, digital marketing bases its strategies on four tools: the web page, on-line positioning, the corporate blog, and social networks. Social networks hold great potential for creating an equal opportunity, powerhouse market with innovative, low-cost goods and services. Among the activities that belong to digital marketing are Internet-based advertising campaigns, sales promotions distributed by cell phone technology using GPS targeting, on-line surveys, and other highly effective e-commerce activities aimed at consumers (Moro & Rodés, 2014).

But also worthy of note are certain internal business processes through which marketing objectives are fulfilled: the use of customer databases, the analytical web, the use of technological systems, and CRM. Members of an organization use these in order to cultivate good relationships with their clients. It should be noted that e-marketing includes practices related to e-commerce, that is, “commercial transactions in which there is no physical relationship between parties, but rather in which orders, information, payments, etc. are transferred via an electronic distribution channel (Fonseca, 2014).

Ultimately, fair trade organizations are faced with the challenge of adopting themselves to this new concept of the market. They must make the technological tools that allow them to learn about, reach out to, and foster loyalty in their customers a daily part of their management practice. To address this need, the fair trade movement, by its nature, must embrace market innovation. Fair trade integrates the concepts of mutual development and equity within its approach to competitiveness, positioning, and profitability. Thus, it enriches the conventional vision of the market with the principles of solidarity and sustainable community development (Alves, 2017). It is vital for the fair trade movement to create commercial pathways and strategies that are adaptable to its situation, ones that respect its principles, values, and objectives, so that the customer becomes more aware and consumes in a way that is fairer, friendlier, and more sustainable. In this respect, digital marketing has the potential to become the tool of the future for raising awareness about aspects of environmental conservation and social well-being. Alternative movements such as fair trade can become the precursors of a grand global initiative.

Given this background, this study will establish the relationship between the commercial management of fair trade retail outlets and the application of ICT to commercial management by analyzing the current situation in Quito. It will also identify the best technological and digital tools for use in fair trade outlets. The results can be used to establish commercial management alternatives that implement ICT, especially those related to digital marketing and e-commerce, yet that do not compromise fair trade principles and objectives. Based on this research, fair trade stores in - Quito will be able to redefine their strategies at the administrative, marketing, sales, and commercial levels. These changes will improve their market position. This article is structured as follows. First, it defines the methodology and the field study site, within which it presents the model it has used to measure the current interaction between commercial management and ICT. Second, it presents the qualitative and quantitative results. Third, it discusses the analysis of the results. Finally, it presents the conclusions based on the analysis.

The study based in - Quito city-capital of Ecuador-. Quito is the second largest city in Ecuador, an important economic, political, and cultural center. According to INEC’s (National Institute of Statistics and the Census) 2010 Economic Census, there are 101,937 business enterprises in Quito, making up 19.9% of all businesses in the country. 89% of them are small businesses. They account for 2.3% of all local sales, and 36% of all employees. In terms of economic divisions, 49% operate in either the wholesale or retail sectors, 10.7% represent housing and food services, and 10.4% are involved in industrial manufacturing. In the case of wholesale and retail outlets, about half belong to the popular economy, that is, they are family or microbusinesses, with annual sales less than USD 10,000 (MDMQ, 2013). Knowing these facts, Quito has been actively working since 2016 to establish itself as a “Latin American Fair Trade City” within the global fair trade campaign. This initiative implies creating resolutions, workgroups, and publicity campaigns to bolster the sale and consumption of alternative products (Coscione, 2015).

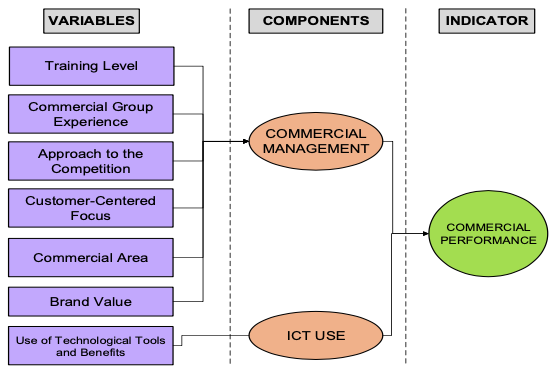

The research covered the second half of 2017, combining both qualitative and quantitative data, a correlational research scope, and a non-experimental, transversal approach. We used primary sources for the data collection, specifically, interviews and surveys of commercial managers and other agents of 15 organizations that promote fair trade in Quito. The interview consisted of 20 open questions. This tool permitted us to interact with the interviewees and obtain information about the fair trade, commercial management, digital marketing, and e-commerce practices of their organizations. The survey consisted of four parts: 1) control data, 2) use of ICT, 3) commercial management, and 4) a model for measuring variables. The last part contained 68 points that were integrated into variables: training level (TL), commercial group experience (CGE), approach to the competition (AC), customer-centered focus (CCF), brand value (BV), and commercial area (CA). These same factors were used to define the components of commercial management and use of ICT (UTICS) that affect the organization’s commercial performance in the end (See Figure 1). We modified this model with a strategic model for sales and marketing developed and validated by Leslier Valenzuela, PhD, at the University of Chile (Aravena, Carreño, Cruces, & Moraga, 2013; D. Nuñez, Parra, & Villegas, 2011; Valenzuela & Martínez, 2015; Valenzuela, Nicolas, Gil-Lafuente, & Merigo, 2016; Valenzuela & Villegas, 2013). We should mention that these survey questions were measured on 1 to 5 Likert scale, where 1 equals “completely disagree” and 5 equals “completely agree.” The variable values were derived from the sum of the answers of the components of each variable.

Figure 1

Research model

From (Aravena, Carreño, Cruces, & Moraga, 2013; D. Nuñez,

Parra, & Villegas, 2011; Valenzuela & Martínez, 2015)

Finally, it used NVivo analytical software to interpret the qualitative data, while it use the SPSS statistical packet for the social sciences to analyze the quantitative data. With these tools, first it obtained the variables’ descriptive statistics, and then completed a correlational analysis of them. Finally, it determined the commercial domain indicator for fair trade outlets.

In Table 2 it lists the descriptive statistics of the variables associated with commercial management and ICT use. One can see that, on average, agents and managers of fair trade organizations in Quito lean towards being completely in agreement with respect to the items presented in the survey regarding commercial management and ICT implementation (part 4 of the survey). Given this data, the agents totally agree that better training and workgroup experience would help them obtain better commercial and organizational results. They agree that their businesses have been carrying out more activities that allow them to build better business-client relationships, and to respond better to customer needs and requirements within the fair trade framework. Moreover, these agents agree that the implementation of ICT, especially tools related to digital marketing, would bring multiple benefits and improvements to their commercial practices.

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics

Variables |

Minimum value of the sum of the responses |

Maximum value of the sum of the responses |

Average value |

Standard deviation |

TL |

15 |

20 |

18 |

1.964 |

CGE |

6 |

15 |

13.33 |

2.44 |

CCF |

43 |

59 |

53.27 |

5.271 |

AC |

10 |

20 |

15.6 |

2.874 |

BV |

7 |

25 |

21.6 |

4.641 |

CA |

50 |

89 |

72.6 |

11.394 |

UTICS |

16 |

110 |

94.6 |

23.28 |

In Table 3 it can see the correlation coefficients that show the relationship between each pair of variables associated with commercial management and the use of ICT. It is clear from the table that the majority of results are not statistically significant, due to the conditions of the study. They show that the sample used was not representative of the population and, moreover, that the variables were measured by criteria that could be considered subjective.

Table 3

Correlation Coefficients

|

Commercial Management |

|||||

Variables |

TL |

CGE |

CCF |

AC |

BV |

CA |

UTICS |

0.169 |

0.474 |

0.617* |

0.208 |

0.811** |

0.498 |

Note: *The correlation is significant to the 0.05 degree (bilateral) |

||||||

**The correlation is significant to the 0.01 degree bilateral) |

||||||

One can see that there is a directly proportional correlation of 0.617 between client-centered focus and the benefits that ICT use brings that is statistically significant. We interpret this as meaning that the more that ICT is implemented, the greater the benefits are in terms of business-client relationships, and the higher the value that agents attribute to it. Also, one can see that Brand Value (BV) has a strong association with use of ICT, since ICT enables clients to learn about both brands and products via digital means. Thus, it increases the capacity of agents to reach the target clientele and gain positioning. Then we used canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to determine the degree of association between the whole set of variables for commercial management and the ICT use variable. We obtained a value of 0.687, which indicates that there is a positive average association between the use of ICT and commercial management. (See Table 4.)

Tabla 4

Canonical Correlation Coefficients

Correlation |

Eigen Value |

Wilks Lambda |

F |

DF Numerator |

DF Denominator |

Sig. |

0.687 |

0.892 |

0.528 |

1.190 |

6 |

8 |

0.398 |

Finally, it can assert that the organizations surveyed have an average indicator of performance in their commercial area of 85%, which indicates that their commercial management practices are highly effective in comparison with their competitors.

Based on the interviews and the first three parts of the survey, it was able to determine that fair trade outlets in Quito ally themselves with the economic sector that produces and markets handicrafts and organic products. Coffee, chocolate, and tea businesses stand out, along with stores selling organic produce. These businesses perceive that fair trade as the new commercial paradigm, a lifestyle based on social justice, and an essential pillar of business. With fair trade, they can assure a marketing domain for small producers, and also a consciousness raising space in which consumers can learn about the entire production chain, and thus make ethical purchases based on high quality and just pricing. Moreover, people involved in fair trade note that the main reason they align themselves with fair trade principles is in order to gain first-hand knowledge about productive potential, and the needs of producers and their communities. In addition, the desire to contribute to the well-being of society motivates them. Fair trade contributes to strengthening these businesses, since direct trade with producers favors quality and guarantees the traceability of product origins. Nevertheless, the interviewees think that strong promotional efforts have not been successful in terms of financing, since once a fair price is paid to all agents in the production chain, there’s very little profit left for the stores. As a consequence, liquidity, investment capacity, and profitability remain limited, which in turn hobble the ability to develop future business opportunities. With regard to the commercial management of fair trade retail outlets, the owners and agents involved think the work is satisfactory for now, thanks to the positive reviews they receive from colleagues, providers, and customers. However, there are aspects of the business that need improvement, especially those related to marketing and sales channels. The way business administration—financing, inventories, and pricing—is managed also needs to be improved, as does distribution. These are key activities for widening the market and generating added value for the customer.

In light of these observations, the retail outlets are eager to take advantage of digital marketing and e-commerce. Digital marketing includes the strategic deployment of computers, information systems, e-mail, Internet services, web page development, and social networks. The last two are essential for supporting publicity campaigns. The social networks most commonly used by fair trade stores are Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. In regard to e-commerce, 50% of the businesses surveyed use it to generate sales, but it comes with certain problems, especially in the areas of logistics and distribution. The businesses surveyed estimate that ICT implementation will bring about an 8% improvement to the task of managing. They anticipate that it will mainly contribute to time management, cost reductions, rapid response capability, organizing production in a better way, efficiency, and information dissemination.

Towards the goal of fulfilling the overall objective of this research, we now present several commercial management alternatives for organizations that promote fair trade in Quito. We have taken into consideration the current conditions under which these businesses operation, and we have recommended the main improvements we feel they should adopt while preserving fair trade principles.

First, it recommends that fair trade stores create and promote their own registered seal or trademark that guarantees the process of productive solidarity throughout their commercial chain. Such a trademark forms part of the promotional initiative of capitalist social change, as well as helping to decrease initial monetary investments.

In terms of commercial management, the main problem is marketing. Therefore, we recommend that stores plan sufficiently. In this regard, stores should develop an integrated traditional and digital marketing plan, which includes an appropriate analysis of the current business position and environment, and an assessment of the competition. The plan should identify strategies, action items and, finally, the procedures stores will use to evaluate progress and target improvements.

Along these lines, one of the main strategies of digital marketing should be to improve a store’s website and presence on social networks. Regarding websites, they must be attractive, with good color combination, photography, and short text segments that are both informative and attention-grabbing. The content should be bilingual (Spanish and English), at the least, and the design must be compatible with various platforms (Piñeros & Gómez, 2017). In terms of social networks, content generation is the highest priority. It recommends that stores post photos; recipes; infographics; videos; gifs; catchy, interesting, and motivational phrases; short paragraphs (20-80 words), etc., related to the business, the store, the products, the trademark, the benefits offered, competitive advantages, and fair trade itself. Moreover, stores should publish frequently, but without overwhelming the user with information.

Along with this, one of the best ways that digital marketers can generate traffic towards their website is through strategic positioning in search engines. There are several free tools designed to control positioning, such as Google Website Optimizer, which permits designers to test various versions of the same content in order to identify which of them captures more search results, and Google Trends, which allows analysts to identify which themes are currently trending in order to add corresponding key works to the homepage (Gananci, 2017). There are also off-the-shelf applications, such as Google Adwords, Facebook Ads, and Twitter Ads, that facilitate search engine positioning. With them, designers can create and show ads for the business every time a user clicks on an ad. Another important strategy is e-mail marketing, which helps cement customer loyalty. E-mail marketing is a tool for sending information on products, the business, fair trade, new offers, promotions, and discounts, in which images, videos, virtual pamphlets, and relevant articles can be embedded. E-mail can include links to the store’s web and social networking site, where news is posted. We should remember, however, that in order to be effective, e-mail subject lines and content should be seductive so that recipients will open them (Nuñez, 2014). Likewise, fair trade agents should not abuse e-communications, or they will become counterproductive; customers who receive too many e-mails often become irritated by this strategy (Mejía, 2016).

Finally, the most innovative sales strategy today is e-commerce. It is essential that fair trade agents receive training in e-commerce. They need to learn about the meta-market and market niches in order to occupy openings and opportunities (Piñeros & Gómez, 2017). Stores should address infrastructure needs to meet trends in home delivery, door-to-door shipping, and packaging. These should be supported by technological infrastructure, especially a website that hosts a product catalogue, a basic price chart, an e-shopping cart, and a way to place orders. For this cluster of activities, and due to the fact that logistics and distribution is one of the hardest pieces to solve in the e-commerce puzzle, it recommends that fair trade outlets create strategic partnerships with food transportation businesses and/or with investors that can facilitate and support these initiatives. It is important that strategic partners adopt homologous principles of solidarity and pursue similar objectives in fair trade, thus contributing to the alternative solidarity network. Also, local home delivery should be prioritized. Store owners and workers can use bicycles or contract cooperative bicycle services to meet delivery needs.

In regard to the alternatives to traditional marketing, it thinks that product displays at points-of-sale are an essential visual persuasion factor. Therefore, we recommend that products be displayed on shelves in such a way that they attract the customer’s attention. We want to emphasize that products should be displayed and grouped according to their characteristics, while also suggesting complementary uses, in order to encourage purchase by association. For example, whole grain flour should be exhibited next to free-range eggs and organic chocolate in bars in order to suggest the idea of creating a cake with these ingredients. Shelves and counters should be creatively decorated with different recycled materials, and should include small, informative product labels or QR code that are readable by cell phone, and price labels—including any promotions and discounts—all without crowding the sales space. Informative pamphlets about fair trade containing new and motivational ideas outside the customer’s knowledge base should be placed strategically throughout the store. These should serve to catch the customer’s attention and to motivate them to make conscientious purchases, thereby generating competitive advantage. Also, at points-of-sale, stores should offer product samples of new products or trendy recipes that customers can use. In addition, other types of activities can be hosted at stores. For example, a store could create a frequent buyer club whose members can access cooking classes, yoga lessons, or health lectures, etc. Stores can also sponsor visits to farms or producer communities, so that customers can communicate with real partners, insert themselves in the value and supply chains, and contact other fair trade organizations.

There is a large amount of bibliographic material—Doherty, Smith, & Parker (2015), Hira & Ferrie (2006), Schmitt & Neto (2011), Valkila & Nygren (2010), among others—that addresses the multiple benefits, both social and economic, that fair trade brings to small producers. It reviews the gains that this social movement is making, including its global recognition, and how it is shaping itself into a diverse and inclusive system with a wide variety of agents, discourses, demands, and strategies. However, over the past few years, experts (Fernández & Verdú, 2006; Fridell, 2005) have observed the movement bifurcating into two trends. Vivas (2006) has called them the “traditional and dominant” and the “global and alternative” paths. The first is led by the big importers and certifiers of fair trade products. These agents dominate the political discourse, basing their arguments on the movement’s original values: non-discrimination, prohibitions on child labor, fair pricing, etc. But this discourse limits the vision of fair trade to the payment of price premiums to marginalized producers—a type of welfare assistance or relief aid—rather than maximizing benefits, increasing sales, and opening new markets. The cost of this older strategy is to ally the movement with multinational corporations and large distribution channels (Coscione, 2014; Hudson & Hudson, 2015). The second wave is led by small shops and points-of-sale which promote a more comprehensive view of the movement. These include all the participants in the fair trade value chain. These stores make strategic alliances with all the agents and with other social movements, without abandoning established solidarity values. Their goal is to transform the dominant political and economic system, defend food sovereignty, and preserve long-term commitment based on solidarity (ACS, 2016). This is why the position of the majority of businesses in this study lean towards the “global and alternative” path. They are focusing their efforts on integrating and consolidating themselves into a united and cooperative commercial chain. They link social transformation to payment of fair prices, dignified work, and raising the consciousness of consumers.

The original concept of fair trade upholds the role of stores and small points-of-sale for alternative products as the key agents in the process of consciousness raising and values transmission. In parallel, it critiques alliances with large-scale distribution channels (supermarkets and multinationals). These have a detrimental effect on the work of solidarity-oriented stores. They control large volume distribution and leave the surplus to the small outlets (Fernández & Verdú, 2006). They call into question business marketing practice and corporate responsibility to society (Larrinaga, 2006). Moreover, they justify their unjust commercial practices as “offering” greater bulk income levels for small producers. The results from this study’s interviews confirm these viewpoints. Fair trade stores perceive the large supermarket chains as their greatest competition, since the big distribution chains do not reference the original concept of fair trade and, by stockpiling great quantities of produce and withholding it from the market, they hinder the flow of commerce.

The fair trade movement promotes the widening and empowerment of local markets (Montagut, 2006; Vivas, 2006). Along these lines, it is illogical to import alternative products that can be produced locally with equivalent social and ecological components and ingredients. This being the case, the stores under study have tried to revive traditional and healthy Ecuadorian products and protect Ecuador’s culture and its handcrafted methods of production. In addition, since importing products has associated ecological costs that cannot justify the benefits of consuming those products, fair trade stores in Quito show little interest in exporting products. Exporting is seen as costly and bureaucratic, offering little beneficial to the exporter. Third, fair trade stores feel it necessary to encourage transformation of the producers and other agents in their own commercial chain. That is, they embrace the idea of using transformative businesses based on alternatives principles—such as arts and crafts practitioners, cooperatives, and family businesses (Fretel, Villegas, & Reyes, 2009)—in order to avoid falling into the hands of large, dominating multinational corporations. In this sense, fair trade stores form the intersection of the value chain. They are the closest information outlet to the consumer.

Now then, considering the importance of fair trade retail outlets, we have found very few studies that explain the problems and management hurdles that fair trade organizations, such as the stores analyzed in the study, face. In 2015, Raynolds and Bennett published a study that examines fair trade organizations and practices in one section of their book. They note that each fair trade organization differs in its mission, values, underlying logic, and governing principles. At the same time, each organization constitutes an innovative, society-oriented business that link market dynamics to social ends. Given the competitive environment, the contradictions imply that fair trade agents must rely on conventional procedures for survival and in order to overcome problems. These organizations have to compete with value chains dominated by corporations that promote a growth model that may, although not necessarily, contribute to a reduction in poverty; this represents a disadvantage for fair trade. Consequently, many of the fair trade organizations studied in this research find it very difficult to survive in the current capitalist market. If we take into account the little importance that many people give to this type of initiative, i.e., ethical consumerism, the task becomes even more difficult. Nevertheless, the organizations examined in this study think that, within the local micro-context, fair trade has managed to strengthen its ability to manage this market niche, since the power to communicate directly with producers allows it to ensure product quality and educate consumers about the history of the products they buy. Fair trade groups raise the awareness of these few consumers and gain a position in their highly competitive market.

On the other hand, it has yet to find earlier studies focused on the commercial management of fair trade stores. This limits our ability to make quantitative comparisons. However, it concludes that, in these organizations, there is a low to medium positive association between commercial management and ICT implementation that is most likely due to the fact that commercial management is not applied consistently within these organizations. It may be the case that these small businesses may not require it, or that businesses learn management strategies empirically with little support from information technology. Besides, the low levels of investment in these businesses results in a weak relationship between commercial management and ICT, since these businesses cannot invest in developing the functional aspects of their enterprise. Given these observations, we suggest that future studies conduct more extensive and detailed research of the conditions under which small fair trade stores and organizations operate, and on the other links in the fair trade chain. In addition, they should include other types of variables that are less subjective and more statistical in order to obtain more precise and objective results.

Fair trade is a global movement embracing a new paradigm in commerce. It is trying to promote an alternative system of marketing whose original goal is to transform current conventional market forces that prioritize wealth and maximize their own benefits at the cost of disadvantaged parties. This system of exchange has the goal of not only seeing that its agents, especially small, marginalized producers, obtain just prices for products that meet specified criteria, but also seeing that society open its eyes in regard to commerce. They do this by establishing long-term relationships based on transparency, respect, democracy, and solidarity. They form solidarity networks that protect the environment, promote equity and food sovereignty, and distribute tasks and benefits fairly. The fair trade movement seeks to invigorate local markets and fair trade stores’ participation in them. Fair trade retail outlets play a key role in the process of raising consumer awareness.

However, we need to understand that fair trade operates within a globalized, ever changing, and highly competitive context in which the consumer has access to ever more information than ever. Given that, these businesses feel the need to respond with innovative tools and strategies that help them adapt and survive in this environment. The use of technological tools provides huge benefits for business management. It forms a highly powerful competitive advantage, and generates value for customers at each stage of the commercial relationship.

From this research on fair trade organizations in Quito, we can conclude that fair trade stores and businesses are poorly recognized in both Quito and throughout Ecuador. Ecuadorian consumers do not understand the significance of fair trade. Generally, they do not value alternative, organic, or traditional products, since price plays a major role in buying decisions. Under these circumstances, fair trade stores and enterprises are generally small scale (between 1 and 9 employees) with a limited ability to invest due to their asset limitations. That is, when stores operate under fair trade conditions, they must pay fair prices to each member in the commercial chain, which leaves them with little excess profit—even though it is more fairly distributed—to invest in business development. These businesses usually occupy the food commercialization sector involving sales of coffee, chocolate, tea, and organic and handcrafted products. We have concluded that the best digital tools for these businesses are websites, social networks, e-commerce platforms, and search engine positioning. Following this line of reasoning, we presented alternatives for commercial management focused on digital marketing, information technologies, and fair trade distribution.

We should underscore the fact that fair trade organizations have a greater chance of succeeding within the organic food and handcrafted products markets when they operate within networked organizations. Mutual collaboration is the strongest of their assets. Thus, these businesses should unite in order to form a local movement that fosters networks that promote national trademarks. These trademarks serve as their representatives within Ecuador and throughout the world, and they inspire trust in their customers.

Oswaldo Viteri Salazar acknowledges financial support provided by the National Polytechnic School of Ecuador, for the development of the project PII-17-06

ACS. (2016). El comercio justo una mirada al sur - origen, redes e impactos. Universidad de Córdoba, 54.

Alves, A. (2017). O mercado do comércio justo. Equatorials, 4(June), 112–125.

Aravena, S., Carreño, C., Cruces, V., & Moraga, V. (2013). Modelo de Gestion Estratégica de Ventas. Universidad de Chile. Retrieved from http://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/112213/Tesis Final - Modelo de Gestion Estratégica de Ventas.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Becker, C., & Arditi, B. (2006). Del comercio libre al comercio justo . Los nuevos defensores de la igualdad en las relaciones norte- sur. Sistema 195, (June 2015), 32.

Beynon, P. (2014). Sistemas de información Introducción a la Informática en las Organizaciones. Editorial Reverté.

Calisto Friant, M. (2016). Comercio justo, seguridad alimentaria y globalización: construyendo sistemas alimentarios alternativos. Íconos - Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (55), 215. https://doi.org/10.17141/iconos.55.2016.1959

Caritas. (2012). Cáritas y el comercio justo desde un modelo de economía solidaria.

Ceccon Rocha, B., & Ceccon, E. (2010). La red del Comercio Justo y sus principales actores. Investigaciones Geograficas, 71(Mx), 88–101.

CECJ. (2011). El Comercio Justo como herramienta de cooperación al desarrollo. Retrieved from http://comerciojusto.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/El_ABC_del_CJ_1.pdf

Coscione, M. (2013). Los desafíos del comercio justo latinoamericano: una aproximación a partir de la Declaración de Río de Janeiro. REVISTA GLOBAL, 54, 80–88.

Coscione, M. (2014). Cambios históricos en la governance del sistema Fairtrade: los productores del Sur ganan voz y protagonismo. Otra Economía, 8(14), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.4013/otra.2014.814.07

Coscione, M. (2015). Ciudades por el Comercio Justo: puentes entre Europa y América Latina. Otra Economía, 9(16), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.4013/otra.2015.916.02

Doherty, B., Davies, I. a., & Tranchell, S. (2013). Where now for fair trade? Business History, 55(2), 161–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.692083

Doherty, B., Smith, A., & Parker, S. (2015). Fair Trade market creation and marketing in the Global South. Geoforum, 67(September), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.015

Dolci, P., Schwengber, C., Guilherme, L., & Gastaud, A. (2012). Mensuração do impacto da adoção de tecnologia de informação (TI) no desempenho organizacional de micro e pequenas empresas. Espacios., 33, 19.

Donaire, G. (2010). Los impactos del Comercio Justo en el Sur. Coordinadora Estatal de Comercio Justo de España, 114–125.

Elfkih, S., Wannessi, O., & Mtimet, N. (2013). Le commerce equitable entre principes et realisations: Le cas du secteur oleicole Tunisien. (Fair Trade Principles versus Implementation: The Case of the Tunisian Oil Sector. With English summary.). New Medit: Mediterranean Journal of Economics, Agriculture and Environment, 12(1), 13–21. Retrieved from http://newmedit.iamb.it/static_content,185,185,new-medit.htm%5Cnhttp://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1382784&site=ehost-live

Fernández, R., & Verdú, J. (2006). El rompecabezas de la equidad: análisis crítico del comercio justo existente. In ¿A dónde va el comercio justo? (pp. 28–40).

Fonseca, A. (2014). Fundamentos del e-commerce.

Fretel, A. C., Felipe, L., Villegas, A., & Reyes, A. R. (2009). Comercio Justo Sur-Sur.

Fridell, G. (2005). Comercio justo, neoliberalismo y desarrollo rural: una evaluación histórica. Iconos, 24(24), 43–57.

Gananci, A. (2017). 6 herramientas gratuitas de Google para mejorar tu SEO.

Herrero, J. (2011). Administración, gestión y comercialización en la pequeña empresa. Editorial Paraninfo.

Hira, A., & Ferrie, J. (2006). Fair trade: Three key challenges for reaching the mainstream. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-3041-8

Hudson, I., & Hudson, M. (2015, July). Una crítica vacilante: ¿cómo el potencial del Comercio Justo disminuye con el éxito? EUTOPÍA - Revista de Desarrollo Económico Territorial - N.o 7, 131–145.

INEC. (2010). Censo nacional económico.

Joyanes, L. (2015). Sistemas de información en la empresa. México: Alfaomega.

Larrinaga, A. (2006). Construir algo nuevo: reubicando el comercio justo. In ¿A dónde va el comercio justo? (pp. 67–76).

Laudon, K. C., & Laudon, J. P. (2012). Sistemas De Información Gerencial. Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Lozano, J. (2011). El comercio justo, soñando con los pies en la tierra. Retos, 1(1), 53–63.

McBurney, M. W. (2010). Las cadenas de valor del café organico/comercio justo de Intag y su impacto en el desarrollo local.

MDMQ. (2013). Situación económica y productiva del DMQ. Retrieved from http://gobiernoabierto.quito.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/documentos/pdf/diagnosticoeconomico.pdf

Mejía, J. (2016). Estrategia de Marketing Digital: herramientas y pasos de implementación. Retrieved from http://www.juancmejia.com/y-bloggers-invitados/estrategia-de-marketing-digital-herramientas-y-pasos-de-implementacion/#24_Email_Marketing

Montagut, X. (2006). Diez retos y una limitación. In ¿A dónde va el comercio justo? (pp. 99–121).

Moro, M., & Rodés, A. (2014). MArketing Digital. Paraninfo.

Nuñez, D., Parra, M., & Villegas, F. (2011). Diseño de un modelo como herramienta para el proceso de gestión de ventas y marketing. Universidad de Chile.

Nuñez, V. (2014). Cómo diseñar una estrategia de email marketing desde cero. Retrieved from https://vilmanunez.com/estrategia-para-email-marketing/

O`brien, J., & Marakas, G. (2012). Sistemas De Información Gerencial. México: McGraw Hill.

Petljak, K., Štulec, I., & Zrnčević, J. (2015). Delighting customers and beating the competition : Insights into mainstreaming fair trade. In Trade Perspectives 2015 (pp. 192–201).

Piñeros, R., & Gómez, L. (2017). How can information and communication technologies ( ICT ) improve decisions of renewal of products and services and quest and selection of new suppliers ? Espacios., 38, 27.

Raynolds, L. T., & Bennett, E. A. (2015). The Handbook of Research Fair Trade. Elgar.

Rodríguez, I. (2014). Marketing digital y comercio eletrónico. Barcelona: Ediciones Pirámide.

Rojas, M. M. (2003). Comercio Justo Como Alternativa En Los Mercados Globalizados. Economia Y Sociedad, 21(21), 93–113.

Schmitt, V. G. H., & Neto, L. M. (2011). Association participation, fair trade and sustainable territorial development: the experience of “Toca Tapetes.” Revista de Gestao USP, 18(3), 323–338.

Stenn, T. (2013). Comercio Justo and Justice: An Examination of Fair Trade. Review of Radical Political Economics, 45(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613412475189

Treviño, A. G. (2013). El impacto del Comercio Justo en el desarrollo de los productores de café. Estudios Sociales, XXII, 271–293.

Valenzuela, L., & Martínez, C. (2015). Orientación al cliente, tecnologías de información y desempeño organizacional: Caso empresa de consumo masivo en Chile. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 20(70), 334–352.

Valenzuela, L., Nicolas, C., Gil-Lafuente, J., & Merigo, M. (2016). Fuzzy indicators for customer retention. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979016670526

Valenzuela, L., & Villegas, F. (2013). Influence of customer value orientation, brand value, and business ethics level on organizational performance. Review of Business Management, 18(59), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v18i59.1701

Valkila, J., & Nygren, A. (2010). Impacts of Fair Trade certification on coffee farmers, cooperatives, and laborers in Nicaragua. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9208-7

Vivas, E. (2006). Los quiénes y el qué, en el movimiento del comercio justo. In ¿A dónde va el comercio justo? (pp. 11–27).

WFTO. (2013). Los 10 Principios del Comercio Justo. Organización Mundial Del Comercio Justo, 4. Retrieved from http://wfto.com/sites/default/files/Los 10 Principios de Comercio Justo 2013 (Modificaciones aprobadas en la AGM Rio 2013 )_Spanish.pdf%5Cnhttp://wfto-la.org/comercio-justo/wfto/10-principios/

1. She had made several consultancies during her student life to several companies in the Quito city. National Polytechnic School of Ecuador. Business Engineer. majo15_mv@hotmail.com

2. He focuses on the analysis of societal metabolism and his studies encompass agricultural activity, supply chains and public policies related to production and the environment. National Polytechnic School of Ecuador. PHD in Environmental Science and Technology. hector.viteri@epn.edu.ec

3. Full time professor, with training in business administration. He is currently taking the PhD program in technological management at National Polytechnic School of Ecuador. xavier.ona@epn.edu.ec

4. Doctor in Administration, with emphasis on organizational management, planning and human talent. Extensive experience in the public and private spheres. Professor at National Polytechnic School of Ecuador klever.mejia@epn.edu.ec

5. PhD. Public Administration, PhD. Political Science, Professor at the University, Technological Israel and Professor at the Complutense University of Madrid. didonoso@ucm.es