Vol. 40 (Number 5) Year 2019. Page 2

Vol. 40 (Number 5) Year 2019. Page 2

ROMERO OLIVA, Manuel F. 1; CORPAS MARTOS, Alberto 2

Received: 02/09/2018 • Approved: 24/01/2019 • Published 11/02/2019

ABSTRACT: Oral communicative competence is traditionally neglected in the development of competence of students in compulsory education. In a highly demanding social and professional context, we must contribute to communication skills in general and to oral skills in particular. Together with this, given the digital and changing context in which we find ourselves, we need to know and master new means of production and reception of messages mediated by technology. Virtual Learning Environments open up an updated field of work that allows for feedback and the extension of the spatial-temporal limits of the classroom for the development of orality. |

RESUMEN: La competencia comunicativa oral se encuentra tradicionalmente desatendida en el desarrollo competencial del alumnado de las enseñanzas obligatorias. En un marco social y profesional de máxima exigencia debemos contribuir a las destrezas comunicativas en general y a las orales en particular. Junto a esto, dado el contexto digital y cambiante en el que nos encontramos, tenemos la necesidad de conocer y dominar nuevos medios de producción y recepción de mensajes mediados por la tecnología. Los Entornos Virtuales de Aprendizaje nos abren un campo de trabajo actualizado que permite la retroalimentación y la ampliación de los límites espaciotemporales del aula para el desarrollo de la oralidad. |

Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) are “digital spaces for education that are configured with a pretended pedagogical purpose” (Álvarez Ramos, 2017:35). For Silva Quiroz (2011:57) VLE allow transition between learning models based on the transmission of knowledge towards those based on the construction of knowledge. This makes the students turn into learners and active agents of their own learning as well as teaching staff adopt the role of facilitator.

Clearly, insofar as education seeks to be a reflection and a means of access to the society in which it is inserted, it cannot -and should not- remain on the margins of this changing situation. Coll Salvador and Monereo Font (2008:43) recognize that education should teach students to interact with the world in which they live and make them capable of solving problems.

As Amar Rodríguez (2017:21) recognizes, the class has been modified by technologies and this fact has affected both teachers and students. Therefore, it is necessary to accommodate certain aspects in the concept of pedagogy itself (Adell Segura and Castañeda Quintero 2012:15). One of the most remarkable things about this new reality of teaching is that, although technology is apparently the axis around which teaching innovation revolves, what is important lies in the model of use that is made of it. It requires a new way of relating information, generating knowledge and organizing judgments, which implies the development of a new pedagogy. This fact has a direct transposition to the teaching performance that must adapt its methodology to this new technological and mediatic environment of the current society. This is necessary since it is intended to offer a new way of teaching in accordance with the current reality, that prepares a student capable of working autonomously in it. (Prado Aragonés, 2001:22, Coll Salvador, Mauri Majós and Onrubia Goñi, 2008:86).

Technology allows us to expand time and limited contact of one hour to thirty students and turn it into personalized attention without space-time limits (Corpas Martos y Rubio Millares, 2017:124).

Taking as a starting point the idea of the effective inclusion of technology in teaching-learning processes, the concept of the Personal Learning Environment (PLE) emerges. We defend the thesis of Adell Segura and Castañeda Quintero (2010:2) in which it is considered that PLE should be a complement to what is already done in the classrooms: "What is evident is that PLEs go far beyond technology and involve profound changes in our usual, personal and collective educational practices." It is, therefore, a pedagogical idea focused on the learning of people beyond the use that can be made of technology, which comes to materialize in tools the framework of knowledge, relationships with content and other learners and strategies that everyone uses regularly to learn.

By definition, in interpersonal communication there is no technological mediation. This fact implies the co-presence of the participants. However, for obvious reasons, these statements seem excessively categorical and, nowadays, the technological mediation configures a multitude of perfectly valid communicative situations that must be configured in an express way according to their particularities.

Electronic communication allows us to shape ourselves as participants in the communication, producing qualitative variations. This modality brings to the conscious plane reflex acts such as non-verbal language, and having to make explicit certain communicative intentions.

The communicative situation is, together with the relationship between the interlocutors and the communicative purpose, the three coordinates that can “serve to establish the complementarity and progression of the didactic sequences” (Jover Gómez-Ferrer, 2014: 78-79) avoid an anecdotal impact of orality in the classroom.

If we talk about the functional division of communicative work, in media communication there is a hierarchy where each individual develops a role (Sampedro Blanco, 2004: 138). In interpersonal communication, however, this system does not exist beyond certain roles from the social point of view. In the everyday environment, communication relies more and more on the non-explicit, above all, on the ability to change the register according to the interlocutor and the intentions of the message.

If we propose a model of interpersonal communication mediated through new technologies, we are developing a proposal for a mixed model that gathers characteristics of the two possibilities described above. On the one hand, there is a hierarchy of roles between the sender and receiver. However, there is a democratic extension of the production of messages, creating what we can call prosumers (Toffler, 1981: 262), so that social roles take on greater importance than others of a more economic or political nature.

We found a problem that we can specify in the low development of oral communicative competence in students of Compulsory Secondary Education. On the way to possible proposals and solutions we will focus on the Virtual Learning Environments (VLE), defined in a broad sense, based on proposals from Belloch Ortí (2012) or Cabero Almenara and Llorente Cejudo (2005), as those digital educational platforms that allow us to develop different methodologies that support communicative development in the classroom context and outside of it. That is why we set ourselves the main objective of developing oral communicative competence through EVA.

We understand that quantitative and qualitative paradigms by themselves can be exclusionary and reductionist. That is why we demand the validity of both methods for educational research and propose overcoming this dichotomy (Rodríguez Sabiote, Pozo Llorente and Gutiérrez Pérez, J., 2006). In our opinion, what Bericat Alastuey (1998) calls segregationist logic, which contemplates the validity of both paradigms, does not make any sense, since this term does not contemplate them as complementary and mergable elements. Against this idea, the integration logic set out by Bericat Alastuey or Gutiérrez Borobia (1996) himself is proposed, taking advantage of the tools that each method can offer at any given time to improve the quality of research. We therefore opted for the combination of both methods.

Following authors such as Latorre Beltrán et al (1996), McMillan and Schumacher (2005) or Sabariego Puig (in Bisquerra Alcina, 2014), we will focus on an interpretive or qualitative paradigm, without renouncing to, therefore, a critical approach. This approach tries to identify the potential for change, which is accompanied by a praxeological vision of the world that “se caracteriza por la constante interacción entre acción y reflexión con el objetivo puesto en la aplicación de los conocimientos para transformar la realidad.” (Sabariego Puig, ibid, 2014: 76). This is the reason why we propose an investigation “from within” the frame of reference or from a natural context, since we approach this work with a double objective: on the one hand, understanding people and their involvement in our object of study and, on the other hand, social transformation. In order to reach this objective of study, we will adopt a holistic perspective, and as researchers we will be part of the process, becoming the main instrument of measurement.

For the realization of an effective and competent investigation, even more within the qualitative and interpretative paradigm, it is necessary to have a in-depth and realistic knowledge of the context in order to adjust the actions to the moment of designing the intervention and, also, for the evaluation of conclusions when it comes to analyze the results obtained throughout the research process. As Simons (2011: 52) points out when setting the limits of the case study, several factors must be taken into account. “Estos límites se extienden más allá de la ubicación física, por ejemplo el aula o la institución, e incluyen a las personas, las políticas y las historias” This research is framed in part of a group of the fourth year Compulsory Secondary Education. It consists of a total of 33 students (20 boys and 13 girls) and it has a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of the section bilingual or non-bilingual and modalities -sciences or Literature and Languages-, although in the same itinerary linked to the academic mathematics. There is also diversity between performance levels with very different efficiency a priori, though with a generally low trend.

We focus on the techniques of survey research described by Torrado Fonseca (2004), the questionnaire and the interview, terms that often appear as synonyms. In our case, we will distinguish both instruments mainly by the mediation of the technologies in the case of the first and the face-to-face meeting in the second. We will also distinguish by their own design, understanding the questionnaire as a closed and planned question repertoire, while in the case of the interview we opt for the semi-structured ones that are “undefined to a lesser or greater degree”. We have created questionnaires formed by questions of a different nature that they intend to establish:

Our teaching work is imbricated in the curriculum of the fourth year of Compulsory Secondary Education, although the methodological proposal with which we work proposes a series of didactic sequences focused preferentially on oral communication skills -parting from the premise of the inseparability of skills in the natural exercise of education and human communication.

In our planning recourse was made to a series of projects distributed at different times of the academic year and that bring with them a series of tasks to be carried out by the teacher and the students in order to establish a greater significance in the teaching-learning processes. We start with the proposals made by Ramos Sabaté (2010) and Romero Oliva (2018) for the effective planning of the tasks understanding that these are made up of different stages that must be attended. From the first model we appropriate the term didactic sequence, since it gives a more longitudinal and progressive idea of the process, as well as the denomination of each of the phases, as we seem more descriptive and precise with the tasks we are going to carry out. On the other hand, from the second model we will take the division of the tasks of teacher and children, which we group in students.

The proposal consisted of two main categories:

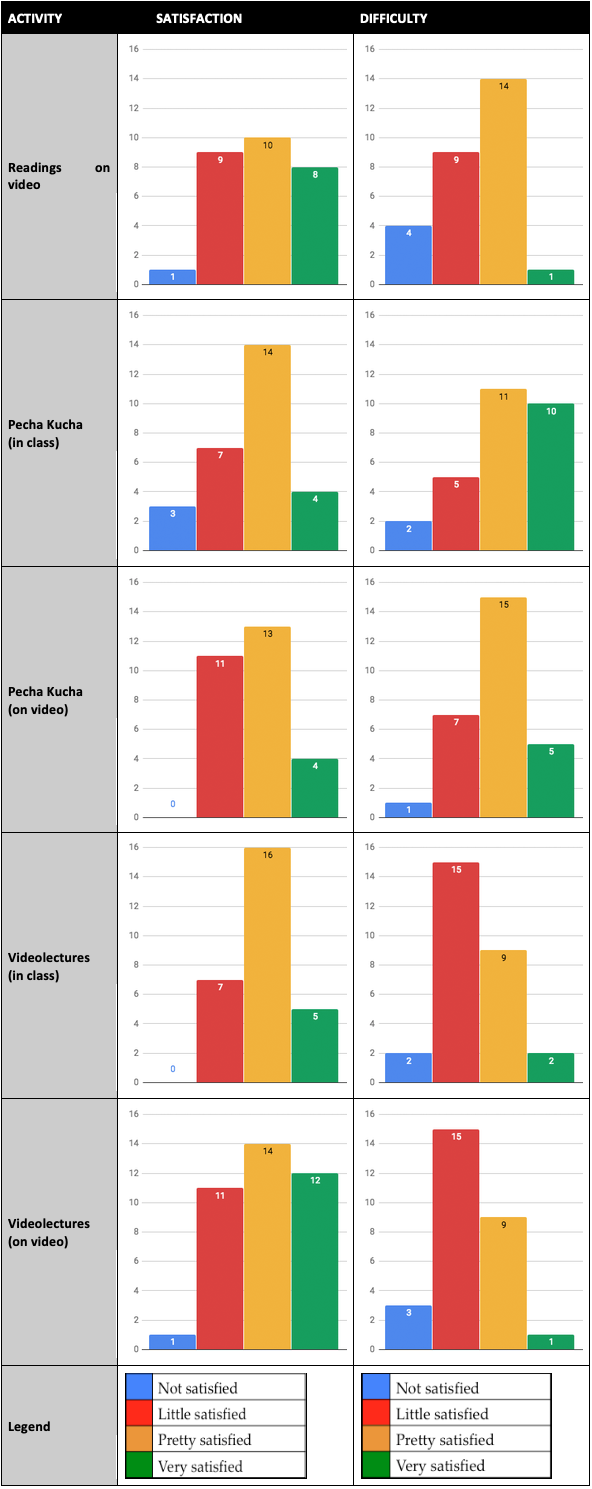

The response of the students was diverse, although satisfactory in general (table 1). They recognized, for example, the enjoyment of the elaboration of Christmas recipes recorded in video, showing their satisfaction for the integration of the technology, the play factor and the group work.

Likewise, integrated projects, in spite of their considerable difficulty and extension, receive a great reception (table 1) due to the fact that they manifest a greater awareness of progress and improvement in their oral skills, at the same time that they successfully manage technologies of which they have good management in their daily life: mobile, video editing or YouTube.

Table 1

Student self-assessment of project satisfaction and difficulty

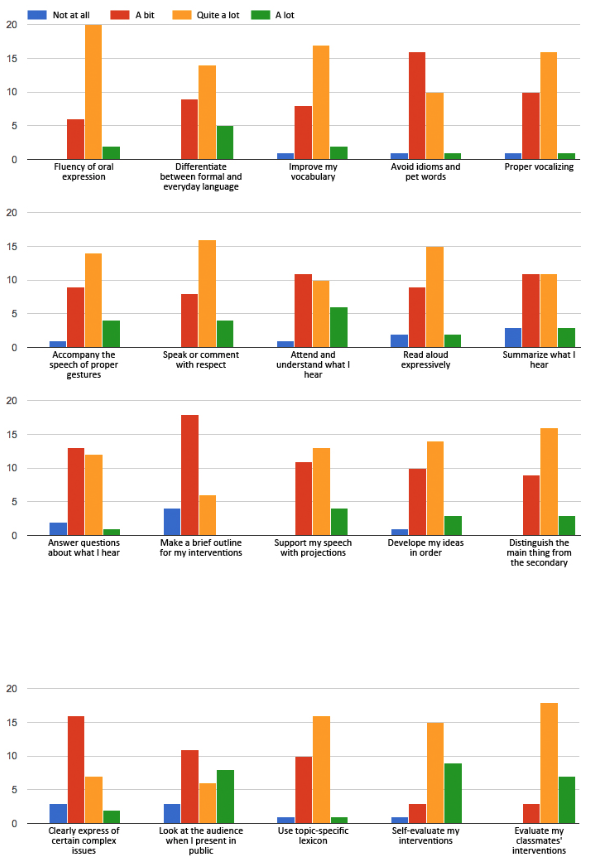

If we reflect the self-assessment that students make of their contribution to the improvement of their oral skills, we can observe that in general they perceive a fairly high grade, although with some reservations that we will comment on in the conclusions.

Table 2

Student self-assessment of the contribution of activities to their oral skills

Although we wanted to highlight the perception that the students have of themselves (table 2), we want to reflect some significant aspects about the perception of the professor participating in the research.

In the light of the data obtained in the study, we can draw some conclusions:

In general, students perceive a significant improvement in orality-related skills thataffect their daily and academic lives.

The introduction of self-assessment and co-assessment led to a high level of ownership of the assessment tools by the learners, which has an impact on their ability to be an active agent in their own learning and that of their peers.

Satisfaction is not linked to the difficulty of the activities but to the introduction of the playful component and connected to their center of interest.

Students perceive that the activities have not contributed significantly to their listening skills. Although it is difficult to attribute this to a lack of contribution or to self-evaluation itself, it is obvious that this is an area for improvement.

In conclusion, based on the data from our study, even taking into account that experience can and should be strengthened and consolidated, Virtual Learning Environments are a useful way to contribute to the development of Oral Communication Competence.

Abascal, M. D. (2010). Evaluación del uso oral como proyecto de centro. Textos de didáctica de la lengua y la literatura, (53), 48-57.

Adell, J. y Castañeda, L. (2010) Los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLEs): una nueva manera de entender el aprendizaje. En ROIG VILA, R. y FIORUCCI, M. (Eds.) Claves para la investigación en innovación y calidad educativas. Studimenti di recerca per l'innovaziones e la qualitá in ámbito educativo. La Tecnologie dell'informaziones e della Comunicaziones e l'interculturalitá nella scuola. Alcoy: Marfil - Roma TRE Universita degli studi

Adell, J. y Castañeda, L. (2012) Tecnologías emergentes, ¿pedagogías emergentes? En Hernádez, J., Pennesi, M., Sobrino, D. y Vázquez, A. (Coord.) Tendencias emergentes en Educación con TIC, pp. 13-32. Barcelona: Asociación Espiral, Educación y Tecnología.

Álvarez Ramos, E. (2017). Las TAC al servicio de la formación inicial de maestros en el área de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura: herramientas, usos y problemática. Revista de Estudios Socioeducativos. ReSed, (5), 35-48.

Amar, V.M. (2017). Ideas para un debate sobre tecnología y educación. Revista de Estudios Socioeducativos. ReSed, (5), 16-28.

Arnao, M. O. (2015). Investigación formativa y competencia comunicativa en Educación Superior (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Málaga, España

Belloch, C. (2012). Entornos virtuales de aprendizaje. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia.

Cabero, J. y Llorente, M. C. (2005). Las plataformas virtuales en el ámbito de la teleformación. Revista electrónica Alternativas de Educación y Comunicación.

Coll, C., Mauri, T. y Onrubia, J. (2008). Análisis de los usos reales de las tic en contextos educativos formales: una aproximación sociocultural. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 10 (1). Consultado el 31 de julio de 2018, en: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol10no1/contenido-coll2.html

Coll, C. y Monereo, C. (2008). Educación y aprendizaje en el siglo XXI: Nuevas herramientas, nuevos escenarios, nuevas finalidades. En Coll y Monereo (Coords.) Psicología de la educación virtual, 19-53.

CORPAS, A. Y RUBIO, R. (2017). Expandiendo el aula a través del microblogging. Revista de Estudios Socioeducativos. ReSed, (5), 119-129.

Cubero-Ibáñez, J.; Ibarra-Sáiz, M. S. Y Rodríguez-Gómez, G. (2018). Propuesta metodológica de evaluación para evaluar competencias a través de tareas complejas en entornos virtuales de aprendizaje. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 36(1), 159-184.

Escandell, M. V. (1993) Introducción a la pragmática. Barcelona: Anthropos

Latorre, A.; Del Rincón, D.; Arnal, J. (1996). Bases metodológicas de la investigación educativa. Barcelona: Hurtado ediciones.

Jover, G. (2014) El aprendizaje de la competencia oral. Lomas, C. (2014) La educación lingüística, entre el deseo y la realidad. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Lomas, C. (2013) Cómo enseñar a hacer cosas con las palabras. Teoría y práctica de la educación lingüística. Volumen I. Barcelona: Paidós.

Martínez Rizo, F. (2012). La evaluación formativa del aprendizaje en el aula en la bibliografía en inglés y francés. revisión de literatura. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 17 (54), 849-875.

Mcmillan, J. H.; Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación educativa. 5ª Edición. Madrid: Pearson Educación.

Núñez Delgado, M. P. (2001). Comunicación y expresión oral: hablar, escuchar y leer en secundaria (Vol. 46). Madrid: Narcea Ediciones.

Prado, J. (2001). La competencia comunicativa en el entorno tecnológico: desafío para la enseñanza. Comunicar, 17, pp. 21-30.

Ramos Sabaté, J. M. (2010). La evaluación de la expresión oral y escrita a través de rúbricas en primero de ESO. Lenguaje y textos, (32), 71-80.

Ramos Sabaté, J. M. (2010). La evaluación de la competencia lingüística y audiovisual. Aula de Innovación Educativa, 17(188), 17-21.

Rodríguez Illera, J. L., y Escofet, A. (2008). La enseñanza y el aprendizaje de competencias comunicativas en entornos virtuales. Coll y Monereo (Coords.) Psicología de la educación virtual (pp. 368-385). Morata.

Rodríguez Sabiote, C., Pozo, T. y Gutiérrez Pérez, J. (2006). La triangulación analítica como recurso para la validación de estudios de encuesta recurrentes e investigaciones de réplica en Educación Superior. RELIEVE, v. 12, n. 2. http://www.uv.es/RELIEVE/v12n2/RELIEVEv12n2_6.htm. Consultado en (26 de febrero de 2018).

Romero, M. F. (2018) Traspasando la frontera de la oralidad en el aula o por qué educar para la vida desde la competencia lingüística. Libro abierto. Recuperado de el 24 de julio de 2018 en: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/educacion/portals/web/libro-abierto/a-fondo/-/libre/detalle/hwqrz6gla416/traspasando-la-frontera-de-la-oralidad-en-el-aula-o-por-que-educar-para-la-vida-desde-la-competencia-linguistica-12dog0txhik5n

Romero, M.F. y Trigo, E. (2018) Los proyectos lingüísticos de centro. Textos de didáctica de la lengua y la literatura, ISSN 1133-9829, Nº 79, 2018, págs. 51-59

Romero, M.F. y Trigo, E. (2010) Didáctica de la lengua y aprendizaje del lenguaje: una aproximación a la enseñanza de la gramática desde las variables del ámbito familiar”. Tonos digital: Revista electrónica de estudios filológicos, núm. 20. Recuperado el 28 de julio de 2018 en: https://www.um.es/tonosdigital/znum20/ secciones/estudios-18-ensenanza_de_la_gramatica.htm

Roméu-Escobar, A. J. (2014). Periodización y aportes del enfoque cognitivo, comunicativo y sociocultural de la enseñanza de la lengua. Varona (digital), 26(58), 32-46.

Rubio, R. (2017). El proyecto lingüístico de centro como respuesta sistémica al reto de la competencia comunicativa en entornos educativos formales. Análisis de casos. (Tesis doctoral) Universidad de Cádiz, España.

Sampedro, V. F. (2004). Identidades mediáticas e identificaciones mediatizadas. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 66-67.

Santos Guerra, M. Á. (1997). El problema metodológico en la educación popular ¡Silencio, comienza la clase de lengua!. Revista de ciencias de la educación: Organo del Instituto Calasanz de Ciencias de la Educación, (172), 351-370.

Silva, J. (2011). Diseño y moderación de entornos virtuales de aprendizaje (EVA). Editorial UOC.

Simons, H. (2011). El estudio de caso: Teoría y práctica. Madrid: Morata

Toffler, A. (1981). La tercera ola. México: Edivisión.

Trujillo, F. (2015) Un abordaje global de la competencia lingüística. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, núme. 459, pp.10-13.

Trujillo, F. y Rubio, R. (2014) El PLC como respuesta sistémica al reto de la competencia comunicativa en entornos educativos formales: propuesta de análisis de casos. SEDLL. Lenguaje y Textos, núm. 39, pp. 29-38.

1. Professor and Director of the department of Spanish Language and Didactics. Cadiz University. Spain. Contact e-mail: manuelfrancisco.romero@uca.es

2. Teacher of secondary education and coordinator of the educational innovation program ComunicA. Spain. Contact e-mail: alberto@clasedelengua.com

3. Plickers is an online tool to design tests, to check the answers with a mobile phone app by scanning the students' personalized cards and showing the results in real time. It can be very useful to assess oral comprehension.

4. PechaKucha is a presentation style in which 20 slides are shown for 20 seconds each (6 minutes and 40 seconds in total). The format keeps presentations concise and fast-paced.