Vol. 38 (Nº 60) Year 2017. Páge 28

Vol. 38 (Nº 60) Year 2017. Páge 28

A.M. ORTIZ-Colón 1; Liz A. OVELAR Flores 2; Lorenzo ALMAZÁN Moreno 3; Miriam AGREDA Montoro 4

Received: 19/09/2017 • Approved: 15/10/2017

ABSTRACT: This research analyzes the organizational culture of the National University of the East (UNE-Paraguay) following the methodology adapted from Hofstede (1999), from the perspective of teachers. For this, a descriptive-correlational design (n = 408) is used, using as an instrument of data collection an ad hoc questionnaire. The results show the trends of the organizational culture of the UNE, finding significant differences between the variables Faculty and seniority in the institution. |

RESUMEN: En esta investigación se analiza la cultura organizacional de la Universidad Nacional del Este (UNE-Paraguay) siguiendo la metodología adaptada de Hofstede (1999), desde la perspectiva de los docentes. Para ello, se sigue un diseño descriptivo–correlacional (n=408), que utiliza como instrumento de recogida de datos un cuestionario realizado ad hoc. Los resultados muestran las tendencias de la cultura organizacional de la UNE, encontrándose diferencias significativas entre las variables Facultad y antigüedad en la institución. |

The attribution of culture to an organisation arose at the end of the 20th century. In recent years, organisational culture has been investigated in numerous countries in national and international companies and institutions (Schein, 2004; García, 2006; Martínez, 2007; Zapata & Rodríguez, 2008; Vázquez, 2008; Agüero, 2010; Pereira, 2010; Britez, Ortiz-Colón & Almazán, 2014).

In studies developed in university contexts and regarding organisational culture, Pelekais and Rivadeneria (2008) have considered the need to incorporate cultural elements such as beliefs, values, rituals, language and history, as a weak perception of culture appeared to be had by their own personnel. On the other hand, Bermúdez-Aponte, Pedraza and Rincón (2015) study the university environment in six universities of Bogotá to get to know the experiences, beliefs and values specific to each institution for being characterising elements. Ochoa, Celaya and González (2016) use seven dimensions (teacher profesionnalisation, organisational management, organisational leadership, organisational cohesion, strategic emphasis, organisational effectiveness and external elements), concluding that an initial stage of raising awareness must be added. Vargas (2011) builds eight index variables ad hoc (teacher identity, social commitment, responsibility, professionalism, industriousness, love of work, companionship, discipline) in his work on the University of Altiplano.

Organisational culture has been defined as a model, some shared ways of thinking and acting (Schein, 2010); a group or society’s way of acting having originated in their beliefs and values that follow an analogous behaviour pattern (Andrade, 1996) or a collective mental programme that distinguishes an organisation from any other (Hofstede, 1999). In our case, the study of organisational culture has focussed on Hofstede’s typology (1991) and Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, (2010) considering it methodologically innovative to identify the own dimensions of its culture as being a University Institution. Hofstede (1999) argues from solid research that all human societies share fundamental problems that have always existed and will continue to exist as long as the human species goes on living. He explains the research results according to differences in values rooted in culture across more than fifty countries.

Cultural dimensions would thus become the visible aspects that are reflected in practices and values being lived out in border institutions like this one (Nelson et al, 2014). In this manner, Hofstede (1999) does not refer to concrete behaviours in themselves, but to the patterns (models, paradigms) of thoughts, feelings, and behavioural potential that people carry in their minds. Similarly, work developed on cross-cultural communication and the use of the web (Hofstede & Hall, 2004) warn that all cultures have a communication system (idiomatic or non-verbal) that includes the basis of their identity and community, displaying visible behaviours and practices, leading us to consider that the most successful cultures in history have been those that can adapt to their environments and change depending on circumstances.

The study carried out is based on a postulate that considers organisational culture as a collective mental programme that distinguishes the members of an organisation from those of another (Hofstede, 1999; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2007a; Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov, 2005; Hosftede, Hosftede & Minkov, 2010; Hosftede & Hall, 2004) from a symbolic vision of culture.

For Hofstede (1999) culture is holistic, in that it refers to a whole which is more than the sum of its parts; it is historically determined by reflecting the history of the organisation; it is socially constructed because it is created and preserved by the group of people that form the organisation; it’s difficult to change; it is related to objects of study from cultural anthropology, such as myths, rituals and symbols; it is fundamentally a programme, in the computing sense attributed to the term.

We understand that the study of organisational culture shows relevance from different points of view: contemporary, as it responds to a current concrete need and is in harmony with the trends of quality control in educational services; it exhibits practical relevance, as the results provided can serve as a basis for decision-making in the corresponding instances, constituting a disciplinary contribution due to the scarce evidence of empirical studies on the subject. This research would therefore be generating valid instruments to perform periodic measurements over time, which also gives methodological relevance to the study. Finally, we believe that this proposal would respond to the need of the University to know itself, in order to have data for decision making that would seek to improve the quality of the educational service being provided by the institution (Brunner, 2009; San Fabián, 2011).

This work therefore contributes to literature on Organisational Culture in Higher Education institutions, covering two areas of research. The first advances in the analysis of the organisations’ culture; the second develops further the studies on organisations’ characteristics according to the adapted dimensions of Hofstede (1999) and Hosftede, Hosftede and Minkov, (2010), from the perspective of teachers in higher education institutions.

Taking as reference the studies and investigations analysed, we suggest exploring the organisational culture of the “Universidad Nacional del Este” (UNE-Paraguay) following Geert Hofstede’s adapted methodology (1999) in the context of a broader research, focussing on the University teachers’ perspective, and getting to know if there are significant differences according to socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, faculty and seniority, together with the rest of the study variables.

This research uses a quantitative methodology based on the descriptive – correlational method. The intention by doing this has been to identify which is the organisational culture of the “Universidad Nacional del Este”. This methodology has been used when wanting to perform the exploration of a certain phenomenon in order to eventually know the real situation and to be able to improve it.

The general objective of the research has been to determine the organisational culture of the “Universidad Nacional del Este” (UNE), based on the classification made by Geert Hofstede (1999) for organisational cultures, as well as to analyse the significant differences between the socio-demographic variables, gender, age, seniority, faculty, along with other variables studied in the research.

The population under study is composed by the UNE’s various faculty members in the 2014-2015 academic year. According to data provided by the University’s Rector’s Office, it includes 718 teachers. To obtain representative samples, Bugeda’s formula (1974) has been applied and compared to Arkin and Colton’s tables (1995), selecting 408 subjects. Regarding the selection of subjects, a type of multistage sampling was used in two phases: a first phase for the assignment of subjects by Faculties, randomly stratified with posterior proportional fixation, and a second for the assignment of subjects to the variables of gender, age and seniority, not probabilistic incidentals. The sample distribution is reflected in table 1.

Table 1

Population and teacher sample

Gender |

Male |

43 |

43,3% |

Female |

56 |

56,7% |

|

Age |

Under 25 years |

8 |

8% |

Between 26 - 45 |

67 |

67% |

|

From 46 to 52 |

9 |

9% |

|

Over 53 |

16 |

16% |

|

Seniority |

Between 1 - 4 years |

39 |

39,3% |

From 5 to 10 years |

40 |

39,8% |

|

Over 11 years |

20 |

20,4% |

|

Faculty |

Polytechnics |

13 |

12,9% |

Philosophy |

36 |

36,2% |

|

Economics |

13 |

12,9% |

|

Agronomic Eng. |

8 |

8,10% |

|

Law |

19 |

18.9% |

|

Health & Science |

11 |

10,8% |

The total of teachers who form part of the simple develop their professional work in the different Faculties of the UNE. From the sample’s total, 43,3% are male and 56,7% female; age is between 26 and 45 years in 67% of the cases. 20,4% have been teaching for 11 years or more, while 39,8% refer to their experience as between 5 and 10 years in the same Faculty.

As a descriptive correlational study (Mateo, 2012), a questionnaire with a type of Likert scale (Thomas y Nelson, 2007) was used ad hoc as a quantitative instrument, aiming at analyzing what organizational culture in the “Unversidad Nacional del Este” is like. This instrument is composed of 43 items with answer options ranging from 1 to 5 (being 1 = fully agree; 2 = agree; 3 = indifferent; 4 = disagree and 5 = strongly disagree). The instrument encompasses six fundamental dimensions, which are the result of the confirmatory exploratory factor analysis, in order to verify the relevance of the latter. Likewise, Bartlett’s sphericity test was performed (χ2 = 60455.740; g.l.= 946; p=.0001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index was calculated (KMO= .842). These values enabled us to perform the factorial analysis, through the principal component analysis method, with a variable rotation, the Varimax and Kaiser procedure. The result of the extraction of the main components reflects that there are 6 factors, where the explained variance is 76.7%, which reveals an optimal balance between the instrument’s components, representative of the theoretical concept. For the study of organisational cultures therefore, the starting point was Hofstede’s six dimensions (1999) to which were tested the answers provided by respondents belonging to various countries – Paraguayans, Japanese and Brazilians.

Once the scale constructed, it was subject to the validation of 12 experts in Educational Sciences from Spanish, Brazilian and Paraguayan universities. After making the modifications and suggestions indicated (in relation to the understanding of the item’s statement as well as its relevance and suitability in each dimension), a validation questionnaire was elaborated through the application of a pilot test in which 30 teachers were randomly selected and not included in the study sample.

For reliability, the Cronbach alpha model was used, .813 being the obtained value, and after the elimination of four items having been considered neutral questions in relation to the subject matter, this reliability coefficient reached .869; therefore, it can be deduced that the questionnaire developed for such research presented very high reliability, as the coefficient was near to 1, a value that reflects a considerable degree of internal consistency (Mateo, 2012). The magnitude of the variable-factor correlations was hence calculated, providing an understanding of Hofstede’s (1999) adapted contents, and enabling us to reorganise the major six factors as such:

The main advantage of the version used was the easy application and understanding of its contents by the recipients.

Once the purpose of the investigation explained to the responsible University and Faculty staff, the data was collected. To do this, at the beginning of 2014, the questionnaires were distributed along with a letter explaining to the teachers the purpose of the research, as well as the content and way of completing and returning the questionnaire. For the statistical treatment of the data, the SPSS programme was used (version 20 for Windows) as a suitable resource for the task. Thus, a descriptive analysis was carried out in which frequency distribution was analysed for each of the questionnaire’s items, the magnitude of the variable-factor correlations of each dimension, as well as the analysis of variance (ANOVA), taking into account the characteristics and response values of the socio-demographic variables studied. It is also worth noting that the analyses carried out were calculated with a confidence level of 95%.

With the intention of analysing the teachers’ evaluations regarding their perceptions of the UNE’s organisational culture, we examined the scores of the means and standard deviations obtained in each one of the items from the different factors that compose the questionnaire.

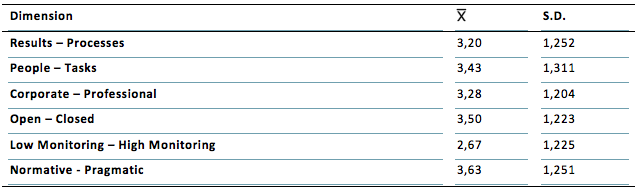

The general results of the dimensions of the UNE’s organisational culture are presented in Table 2, where it can be seen that the normative-pragmatic dimension obtains the highest mean, and the dimension of high monitoring / low monitoring obtains the lowest mean. On the other hand, we would note that the smallest dispersion arises in the corporate-professional dimension (S.D.=1,204) with the highest dispersion in the people-tasks dimension (S.D.=1,311).

Table 2

General results of the UNE’s organisational culture

The results obtained within each of the factors refer to each item’s scores in the questionnaire. In relation to the factor “process-results” (Table 3), the average stands out regarding the item I like undertaking new challenges in the Faculty, which achieved the maximum score (= 3,96; S.D.=1,102), whose standard deviation obtained the lowest score within the factor; the score reached an average of 3,60 (S.D.=1,170) in the item referring to the challenges and undertakings at work… are dependent on final achievement rather than process details. The item that achieved the lowest means was In the Faculty, every day is similar because the same always happens, obtaining an average score of 2,5 (S.D.=1,348), which indicates that the results show a greater dispersion.

Table 3

Process-results

Culture oriented towards results rather than processes |

|

S.D. |

1. Every day there are new challenges and undertakings in the Faculty |

3,29 |

1,225 |

2. In the Faculty, more importance is given to results rather than processes |

3,48 |

1,152 |

3. Challenges and undertakings here are dependent on final achievement rather than process details |

3,60 |

1,170 |

4. In the Faculty, every day is similar because the same always happens |

2,50 |

1,348 |

5. I like taking on new challenges in the Faculty |

3,96 |

1,102 |

6. In the Faculty, every day is very encouraging because there is always a new challenge to face |

2,87 |

1,308 |

7. In the Faculty, I am bored with monotony, it is always the same |

2,69 |

1,423 |

8. Innovations that are constantly being carried out in the Faculty seem very positive to me |

3,1 |

1,28 |

The feeling of teachers is that of not being supported when they have a problem that may affect their working life, a high response dispersion having been observed. On the other hand, the average score with regards to the knowledge of the institution’s aims and objectives is contradicted by sharing decisions in the team or group with an average score of 3,54, as can be observed in table 4. The teachers’ unawareness is confirmed regarding the Faculty’s institutional goals with an average score of 3,50 (S.D.= 1,369). Finally, the average score obtained in the item My opinion is ignored in the Faculty, which achieves a means of 3,42 (S.D.=1,164).

Table 4

People-tasks

Culture oriented towards people rather than tasks |

|

S.D. |

9. In the Faculty I feel supported when I have a personal problem that may affect my work |

3,34 |

1,37 |

10. Important decisions are taken as a team, in a group, in committees or in a college body |

3,54 |

1,36 |

11. The executives of the Faculty implement mechanisms of interest for the well-being of people who study or work in the institution |

3,40 |

1,28 |

12. The aims and objectives of the Faculty are known only by the highest executives |

3,50 |

1,31 |

13. In the Faculty, important topics for the institution are decided in groups |

3,41 |

1,29 |

14. Those who lead the Faculty demonstrate concern for people’s safety |

3,33 |

1,33 |

15. Those of us who work here are unaware of what the institutional goals of the Faculty are |

3,50 |

1,36 |

16. My opinion is ignored in the Faculty |

3,42 |

1,16 |

Teachers express a high average score (= 3,7) implying that it is more important to maintain good relationships among colleagues than to argue over issues and cause clashes between members. On the other hand, it was verified that according to the teachers, those who have friends or relatives in the management team benefit from privileges and advantages in the Faculty (Table 5). Friendly relationships with managers get a significant average score, with the dispersion of response being low. On the other hand, teachers’ attendance to congresses and conferences obtains the lowest average score of the dimension, near to the item’s mean (=2,96).

Table 5

Corporate-professional

Culture is defined as more corporate than professional |

|

S.D. |

17. In the Faculty it is more important to maintain good relations between people, rather than to argue about a subject that can makes us confront one another |

3,71 |

1,17 |

18. In the Faculty, friends or relatives of management enjoy many privileges |

3,29 |

1,28 |

19. Teachers periodically attend congresses and conferences, in order to be updated and trained |

2,96 |

1,13 |

20. In the Faculty, it is more important to maintain good relationships, rather than separating institution members |

3,45 |

1,20 |

21. Friends and relatives of management receive the most advantages in the Faculty |

3,16 |

1,26 |

22. Teachers are selected according to friendship and family ties, rather than competence and ability |

3,1 |

1,14 |

Institutional information is considered by most teachers with a lot of secrecy. On the other hand, we find that teachers admit that they do not facilitate the incorporation of new members in the Faculty. Thus, in relation to item 24 When I entered into the Faculty, I felt at home, teachers at Faculty level do not agree with the item’s statement. Similarly, the behaviour of item 25 When a new member is added to the team, most people do everything possible is rejected by teachers in different Faculties with an average score of 3,79. The item that obtains the lowest average score is item 27 In the Faculty people are not suitably informed of institutional issues as appropriate (=2,89;S.D.=1,325). The means of the items referring to new student integration obtained averages with high scores, as can be observed in item 28 (see table 6).

Table 6

Open-closed

A more open than closed organisation |

|

S.D. |

23. In the Faculty, institutional information is handled with much secrecy, as if everything were secret |

3,41 |

1,13 |

24. When I entered into the Faculty, I immediately felt at ease, as if I were at home |

3,61 |

1,20 |

25. When a new member is recruited, there is an attempt to make them feel accepted and supported |

3,5 |

1,20 |

26. When you enter into this Faculty, senior staff make you go through unpleasant situations |

3,79 |

1,32 |

27. In the Faculty, people are not suitably informed of institutional issues as appropriate |

2,89 |

1,32 |

28. When a new member joins the Faculty, we worry that he feel integrated |

3,5 |

1,22 |

29. In the Faculty, newcomers are not very accepted by seniors |

3,91 |

1,15 |

30. In the Faculty, there is an open and participatory communication system |

3,61 |

1,20 |

The answers to items indicate a very high average score of teachers in relation to management’s personal characteristics (=3,2;S.D.=1,24). Managers are considered a joke by teachers, with a high average score (see table 7). The lowest average score can be found in teachers’ answers to item 35 the correct completion of the task, that is, the completion of the task not causing discomfort or worry.

Table 7

Low monitoring-high monitoring

An organisation oriented more towards low monitoring rather than high monitoring |

|

S.D. |

31. We often make jokes about personal or professional characteristics of managers |

3,28 |

1,24 |

32. In the Faculty, a task gone wrong makes us laugh and tell jokes about it |

2,72 |

1,28 |

33. Neglect in a work process is considered to be a topic for joking in the Faculty |

2,55 |

1,11 |

34. In the Faculty, we have fun joking about management |

2,49 |

1,28 |

35. When a task goes wrong, it does not bother us |

2,31 |

1,19 |

In the normative-pragmatic dimension (where normative has a value of 5 points and pragmatic has a value of 1 point). According to the results produced in the obtained answers, teachers have cultures that are oriented to “normative” with an average that varies between 3,98 and 3, in items 39 In the Faculty, rules are followed no matter what, and43 If a student cheats during an exam, this is considered natural in the Faculty, respectively. According to all the data collected, it is more oriented towards norms, as can be seen in table 8.

Table 8

Normative-pragmatic

The UNE’s orientation is more normative than pragmatic |

|

S.D. |

36. In the Faculty, established norms are not respected |

3,82 |

1,23 |

37. I believe the end justifies the means |

3,55 |

1,21 |

38. Personal ethics and honesty are highly valued in the Faculty |

3,80 |

1,20 |

39. In the Faculty, rules are followed no matter what |

3,00 |

1,21 |

40. In the Faculty, the most valued people are those who show respect for institutional values |

3,67 |

1,23 |

41. In the Faculty, we are proud to have executives who respect institutional norms |

3,67 |

1,22 |

42. In the Faculty, lies are often used to harm a colleague in order to get an advantage |

3,55 |

1,26 |

43. If a student cheats during an exam, this is considered natural in the Faculty |

3,9 |

1,41 |

Considering the socio-demographic variables, gender, age, seniority and Faculty, we carried out a variance analysis (ANOVA), one per variable, in order to know if they influence questionnaire results and if there are differences between groups considered as variable, finding significant differences in the variables of seniority in the institution and Faculty.

In order to determine possible differences between the variable “seniority in the institution” and the rest of the items in the questionnaire, a univariate analysis of the variance was carried out (ANOVA). The items described are those in which this significance has been verified with a value below .05, analysing between what groups such differences occur with a level of confidence of 95%. In the dimension of people-tasks, the seniority variable is significant in four out of the eight items that constitute it, decisions (F=2.603; p=.036)”, “well-being(F=2.868; p=.024)”, “ends(F=3.583; p=.007)” and “ignorance(F=2.817; p=.026)”. Attending to values F(3,583) and p(,007), the dependence is strong between the two variables, since of all the statistically significant differences found, these values surpass the others in the person-tasks dimension.

The descriptive variable “Faculty” has influence on the responses of those surveyed on each item of the questionnaire. With a level of confidence of 95%, it is accepted that there are differences between the means of the groups. It is the variable that most differentiates among teachers, especially in the “normative-pragmatic” dimension, in the items “honesty(F=6,596; p=.000)”, “norms(F=4,643; p=.000)”, “institutionals(F=2.825; p=.017)”, “proud(F=7,249; p=.000)” and “harm(F=6,744; p=.000)”. Based on the normative-pragmatic dimension and the Faculty variable, the item with which it has the highest dependency relationship is In the Faculty, we are proud to have a management team that respects norms, and although there are several crosses that obtain p= ,0000 the value F=7,249 is the greatest in relation to the rest of the items.

This work has attempted to analyse the perceptions of teachers regarding the UNE’s organizational culture (Hofstede, 1999). Thus, teachers in the research have expressed the University’s tendencies in relation to the cultural dimension of the study: processes/results; people/tasks; corporative/professional; open/closed; low monitoring/high monitoring and normative/pragmatic.

This study has revealed differences between teachers depending on their Faculties of origin, fundamentally in the normative-pragmatic dimension. In relation to the seniority of the teaching staff, differences have also been observed regarding people in decision-making, in the institution’s well-being, in the ignorance of institutional goals and the ends of the latter. In line with work by Vargas (2011) and González, Ochoa, and Celaya (2016), where employees identify with their profesionnalisation, we found results in the study that are nearer to a less formal and less specialised education for the work they have to develop, being more oriented towards corporate cultures.

The conclusions of the study have made it possible to get to know the organisational culture in this Educational Institution in order to improve the quality of services it provides and to generate cultural policies for the achievement of institutional objectives. Culture becomes, according to the position taken in this research, like the mental software of the organisation’s members, who perform their learning in the same context, and this is what determines the course to be taken by the organisation ((Ho & Peng, 2016; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2010; 2007b; Hofstede, 1999).

As a final conclusion we find that, based on the results, the Universidad Nacional del Este’s organisational culture following Hofstede’s adapted dimensions (1999) is more oriented towards results, people, as well as corporate, open, high monitoring and regulatory aspects. Based therefore on the work done, this study can mean a first diagnosis, which would lead to a more effective leadership of its managers. If culture expresses socially consensual dominant values, and education is seen as a process of internalisation of values, we believe that the knowledge of the UNE’s organisational culture is an instrument to orient towards an Educational Institution par excellence, aligned with the institution’s social responsibility (Martínez, 2014).

Although the study cannot be generalised to other universities, Hofstede’s validated and adapted instruments could be applied to other university studies in order to know their organisational cultures, with the ultimate aim of knowing and comparing the different cultures as well as detecting if there are differences and/or significant similarities between each of them. This would be of great importance as a contribution to decision-making in Higher Education.

Agüero, M. T. (2010). El cambio estratégico, el liderazgo y la cultura organizacional: Su papel en la competitividad de la organización. Extracted 31st december 2015 from http://www.calidad.org/pu-blic/curric/aguero__torres_maria_teresa.htm

Andrade, H. (1996). La comunicación positiva y el entorno organizacional. En Razón y Palabra, 4(1). Recovered from http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/anteriores/n4/andrade.html

Arkin, H. & Colton R. (1995). Métodos Estadísticos. México: Ed. Continental.

Bermúdez-Aponte, J. J., Pedraza, A. & Rincón, C. I. (2015). El clima organizacional en Universidades de Bogotá desde la perspectiva de los estudiantes. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 17(3), 1-12. Recovered from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol17no3/contenido-bermudezetal.html

Brítez, V., Ortiz-Colón, A.M. & Almazán, L. (2014). Metodología aplicada en el estudio sobre las culturas organizacionales de las empresas paraguayas del alto Paraná-Paraguay. Aula de encuentro, 1(16), 121-137.

Brunner, J. J. (2009). Apuntes sobre sociología de la educación superior en contexto internacional, regional y local. Revista Estudios Pedagógicos 2, 203-230. Recovered from http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/src/inicio/ArtPdfRed.jsp?iCve=173514137012

Bugeda, J. (1974). Manual de técnicas de investigación social. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos.

García, O. (2006). La cultura humana y su interpretación desde la perspectiva de la cultura organizacional. Pensamiento y gestión, 22, 143-154.º

Ho, S. S., & Peng, Y. P. M. (2016). Managing resources and relations in higher education institutions: a framework for understanding performance improvement. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16, 279-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.1.0185

Hofstede, G.H., Hosfstede, G.J. & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Sofware of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. Nueva York: McGraw-Hil.

Hofstede G. & Hofstede G. J. (2007a). Kultury: organizacje, wydaine il zmienione. Varsovia: Polkie Wydawnictivo Ekonemiczne.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede G.J. (2007b). Lokales Denken, globales Handelu: Interkulturelle Zuammenarbeit und globales Management. Varsovia: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne S.A. (PWE).

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J. & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: sofware of the mind. 3ª ed. EE.UU.: McGraw- Hill profesional

Hofstede, G. & Hall, E. (2004). Cultura y Contexto: Un Resumen de las Teorías de Geert Hofstede y Edward Hall sobre la comunicación transcultural y la usabilidad en la Red. Recovered from www.filippsapienza.com

Hofstede, G. (1999). Culturas y Organizaciones. El software mental. La cooperación internacional y su importancia para la supervivencia. Madrid: Alianza.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival. Software of the Mind. Londres: Harper Collins.

Martínez, L.M. (2014). La responsabilidad social corporativa en las Instituciones educativas. Estudios sobre educación, 27, 169-151.

Martínez, A. E. (2007). La significación en la cultura: concepto base para el aprendizaje organizacional. Universitas Psychologica, 6 (1), 155-162.

Mateo, J. (2012). La investigación ex post-facto. En R. Bisquerra (coord.), Metodología de investigación educativa (pp. 195-229). Madrid: La Muralla.

Nelson, N., Barrera, E.S., Skinner, K. & Fuentes, A.M. (2014). Language, culture and border lives: mestizaje as positionality. Cultura y Educación, 28 (1), 1-41.

Ochoa, S.; Celaya, R. & González, R.A. (2016). Cultura organizacional y desempeño en instituciones de educación superior: implicaciones en las funciones sustantivas de formación, investigación y extensión Universidad & Empresa [en linea] 2016, 18 (Enero-Junio) Recovered from http://oai.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=187244133007

Pelekais, C., & Rivadeneira, M. (2008). Cultura organizacional y la responsabilidad social en las Universidades públicas. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 14(1), 140-148.

Pereira, M. (2010). Las dimensiones de la cultura organizacional: El pensar antropológico y psicosocial. Recovered from http://web.house.com.ar/users/hf_crm/concepcion.txt

San Fabián, J. L. (2011). El papel de la organización en el cambio educativo: la inercia de lo establecido. Revista de Educación, 356, 41-60.

Schein, E.H. (2010). Organizational Culture and Leadership, vol. 2, San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Schein, E. (2004). The role of the founder in creating organizational culture. In Wren, D. Hicks, & T. Price (Eds.) Modern classics on leadership, pp. 443-458. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Thomas, J.R. & Nelson, J.K. (2007). Métodos de investigación en actividad física. Barcelona: Paidotribo.

Vargas, R. (2011). Cultura y desarrollo organizacional en la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano - Puno. COMUNI@CCIÓN: Revista de Investigación en Comunicación y Desarrollo, 2(2), 5-16.

Vázquez, M. (2008). Claves para una relectura organizativa desde los paradigmas sociológicos. Espacio abierto, 17(1), 27-52

Zapata, A. & Rodríguez, A. (2008). Gestión de la cultura organizacional. Cali: Universidad del Valle. Facultad de Ciencias de la Administración.

1. Department of Education, Faculty of Education, University of Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas, s/n, Jaén. (23071, Spain). Email: aortiz@ujaen.es

2. Department of Education, University National del Este- UNE, FACISA, Campus Km 8 Acaray, Ciudad del Este. Paraguay. Email: lizovelar@yahoo.com

3. Department of Education, Faculty of Education, University of Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas, s/n, Jaén. (23071, Spain). Email: lalmazan@ujaen.es

4. Department of Education, Faculty of Education, University of Jaén, Campus Las Lagunillas, s/n, Jaén. (23071, Spain). Email: magreda@ujaen.es